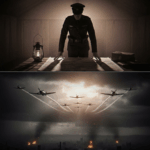

Armor met armor in the hedgerows of Normandy, and for a time the results were almost entirely one-sided. In the summer of 1944, American tank crews rolled into France in Sherman tanks that were brave but badly outmatched. German Panthers and Tigers could destroy them from far beyond effective American range. Crews joked grimly that they were riding in “steel coffins.” Many stopped joking at all.

Against that backdrop of lopsided battles and desperate improvisation, a quiet, unlikely figure stepped into the story: a 34-year-old steelworker-turned-technician named Robert Sterling. He had no degree, no rank, and no permission to rewrite the rules of armored warfare.

But that’s exactly what he did.

This is the story of how a man who failed high school physics helped create a new kind of anti-tank ammunition, changed the psychology of the battlefield, and then disappeared from the official record for decades.

A Battlefield Crisis Measured in Ratios

By June 1944, the problem was obvious to every American tanker in Normandy.

German Panther tanks could knock out a Sherman from well over a kilometer away. In contrast, a Sherman’s 75 mm gun had to close to a few hundred meters and attack from the flank to have any real chance. In frontal engagements, American rounds often struck, sparked, and bounced away. German armor and sloped plate design turned many hits into harmless impacts.

The result was brutal arithmetic. After some early clashes, informal estimates suggested that German tanks were destroying American vehicles at ratios of four or five to one in direct confrontations. Crews described seeing comrades’ tanks hit and disabled before they could react, sometimes so quickly that hatches never opened.

Morale suffered. Some tankers wrote farewell notes before every battle. Others quietly tried to avoid being sent into situations where they knew their chances were slim. Senior commanders understood that this was not just a technical problem, but a psychological and operational one. If tank crews believed their weapons could not defeat enemy armor, the entire combined arms system suffered.

The U.S. Ordnance Department tried every conventional approach. Larger guns strained the Sherman’s chassis. High-explosive rounds that worked well against bunkers simply broke apart on thick, angled armor. Concentrated fire from multiple tanks did not help much if no single shot could reliably penetrate. The underlying issue was simple: steel against steel, with the German side enjoying better metallurgy and geometry.

To change the outcome, someone would have to change the rules.

The Technician Who Watched Steel Fail

Robert Sterling was not the sort of person anyone expected to revolutionize munitions design.

Born in Pittsburgh in 1910, the son of a coal miner, he left school early to work in steel mills. He became a welder and then a lab technician, eventually finding his way into a research facility run by a major steel company. Officially, he prepared samples and recorded data for experiments devised by others.

Unofficially, he watched.

Years of welding and working with metals gave him a kind of intuitive understanding that didn’t show up on transcripts. He could feel when a piece of metal was on the edge of failure, hear subtle differences in the way steel rang under impact, and recognize when heat and pressure were about to do something unusual.

In 1943, while assisting with tests on drilling equipment for industry, he saw something that stuck with him. A tungsten-carbide drill bit, under high speed and pressure, did not simply cut hardened steel. It appeared to melt its way through a test piece. At the point of contact, the combination of force and friction produced temperatures high enough to soften or liquefy the steel, while the tungsten tool remained intact.

Sterling became fascinated by this effect. After hours, using scrap material and spare machinery, he experimented with different speeds, pressures, and angles. It wasn’t about weapons—at least not at first. He was studying how materials failed under extreme stress.

Then a letter from Europe changed his focus.

From Drill Bits to a “Witch’s Bullet”

In early 1944, Sterling received a letter from a cousin serving as a Sherman tank commander in England. The letter described the helplessness of facing German heavy armor, and the loss of a close friend inside a burning tank.

The account hit him hard. The abstract problem of steel against steel now had a face.

Sterling went back to his observations about tungsten and extreme pressure. The standard approach to defeating armor was to make shells bigger and heavier, relying on mass and momentum. What if the key variable wasn’t mass at all, but speed?

Kinetic energy—he knew from the physics he’d once failed in school—increases with the square of velocity. Double the speed, and you get four times the energy. If a smaller, extremely dense core could be launched at much higher velocity, it might focus enough force on a small area to push armor beyond its limits.

The concept that took shape in his mind was simple in outline and radical in practice:

Use a very dense core, such as tungsten carbide.

Surround it with a lightweight “shoe” (a sabot) that allows it to be fired from an existing gun barrel.

Let the sabot fall away in flight, leaving the slender core traveling at far higher speed than a full-bore shell.

At impact, such a projectile wouldn’t rely on blast or fragmentation. It would rely on pure kinetic energy, turning armor into its own worst enemy by forcing it to absorb more stress than it could withstand. The result inside a target tank would be a violent rush of heat and material, potentially disabling systems and making survival extremely difficult.

Sterling sketched designs on whatever was at hand. He knew the idea would face skepticism. Tungsten was rare and expensive, manufacturing tolerances would be demanding, and there was no guarantee the concept would work in the field.

His supervisors did more than doubt him—they ordered him to stop. Official projects were already underway; unauthorized experiments with scarce strategic materials were not welcome. Continuing could have cost him his job.

Instead of giving up, Sterling took a risk that might have ended his career.

The Unauthorized Prototype

Working at night in an improvised workspace, Sterling quietly assembled a prototype round:

A tungsten-carbide core, carefully machined by hand.

An aluminum sabot designed to fit a 76 mm gun.

A configuration meant to discard the outer “shoe” after leaving the barrel, sending the dense core forward at extreme velocity.

He had no tank range to test it on, no formal support, and no permission. So he did something audacious. He packed the prototype, his calculations, and a letter into a crate and mailed it directly to a U.S. Army proving ground.

In his letter, he did not pretend to be anything he wasn’t. He explained that he was a technician, not an engineer, and that his idea might be flawed. But he asked for one thing: a fair test. If the round failed, he wrote, they could discard it. If it worked, lives might be saved.

For weeks, there was no response. Then, unexpectedly, military officers arrived and transported him to the test facility.

On the firing line, his design was loaded into a gun aimed at a captured German tank hull set at a challenging angle and distance. When the weapon fired, the impact appeared almost unremarkable—no dramatic explosion, just a sharp strike.

What the inspection team found after walking up to the target, however, was anything but ordinary: a clean, narrow hole through the armor and extensive internal damage.

The physics had not been cheated. They had been harnessed differently.

The test team concluded that the concept was sound. If it could be manufactured reliably and in quantity, it might transform tank engagements.

Sterling, the high school dropout whose ideas had been labeled impossible, was suddenly at the center of a critical ordnance project.

From One Round to Thousands

The new round—eventually known as a high-velocity armor-piercing (HVAP) type—promised a way for existing guns to defeat heavier armor. But promise alone was not enough. The real challenge lay in production.

Everything about the design demanded precision. The tungsten core needed exact dimensions. The sabot had to hold the core securely during firing and release it cleanly afterward. Propellant charges had to be calibrated so the projectile reached the required speed without damaging the gun.

Sterling insisted on tight quality control. Every flaw in manufacturing would translate into a missed shot or a failed penetration in combat. On the battlefield, “almost good enough” was another way of saying “someone doesn’t come home.”

Initial batches were small, earmarked for frontline testing. Reports from units that received early shipments were cautious at first, then increasingly enthusiastic. Crews described enemy tanks being disabled at ranges that previously had been futile. Where earlier shells had bounced, the new ones bit.

Importantly, the effect was not only physical but psychological. Tank crews who had once felt hopeless now had a tool that could give them a fair fight. On the other side of the front, German crews confronted the unnerving reality that armor they had trusted could be defeated more often, at longer ranges.

The balance of confidence—so vital in armored warfare—began to shift.

Innovation, Resistance, and a Quiet Legacy

Sterling’s contribution did not unfold in a straight line. Bureaucratic resistance, concerns over safety, and the sheer difficulty of scaling a complex design all threatened the project at various points. At least once, the effort was nearly shut down, only to be salvaged by officers who believed in the results they were seeing from the field.

There were other dangers as well. Once it became clear that these new rounds were having a real effect, German intelligence tried to understand and counter them. Sabotage efforts targeted supply chains and processing facilities. For a time, tungsten shortages slowed production. But the depth and flexibility of Allied industry allowed work to continue, if at reduced pace.

By late 1944, the new ammunition was being issued widely to units across Europe. In critical urban battles, where heavy German tanks sought to dominate chokepoints, HVAP-type rounds played a quiet but important role in blunting counterattacks and keeping offensive momentum.

When the war in Europe ended, the weapon remained—but the man behind its breakthrough largely vanished from view.

Security concerns and institutional pride both played a part. In the early Cold War environment, details of advanced munitions were tightly controlled. At the same time, official histories tended to credit teams and formal programs rather than an individual who had once worked around the system. For many years, Sterling’s role was obscured in classified files and generalized descriptions of “ordnance research.”

Yet his innovation did not disappear. Variants of the same basic idea—dense, high-velocity penetrators fired from saboted carriers—became standard across the world. Postwar conflicts saw further refinements and new materials, but the core concept remained remarkably consistent.

What the Story Really Shows

The technical impact of Sterling’s work is clear enough: a new kind of anti-armor ammunition helped close a deadly capability gap at a crucial moment, improved survivability for Allied crews, and reshaped how future tank guns would be designed.

But the human story is just as important.

Sterling’s path was anything but conventional. He was not a senior engineer. He did not have a doctorate or a string of publications. He began as a welder who noticed things others overlooked, refused to dismiss his own observations, and was willing to risk his position to push an idea he believed could save lives.

His experience also highlights the tension between innovation and institutions. The same systems that eventually adopted and fielded his design initially rejected it, and later tried to subsume it into a more comfortable narrative about orderly development and credentialed expertise.

In the end, the rounds he helped create became widely known, while his name almost disappeared.

Today, in museums and reference books, visitors and readers see sleek projectiles and technical diagrams. They see the outcome of a concept, not necessarily the person who spent long nights in a small workshop turning scrap metal and a stubborn idea into working reality.

Remembering Robert Sterling’s story doesn’t just honor one man. It underscores a broader truth: critical breakthroughs often come from unexpected places—from people outside formal hierarchies, who persist even when “the way things are done” seems unmovable.

In the summer of 1944, that persistence helped give American tank crews something they had been missing: a fighting chance.

News

PATTON UNFILTERED: What His Personal Jeep Driver Saw—The Untold, Intimate Story of the Legendary General!

The old man laughed when he talked about dropping a jeep engine in forty minutes. “I took an engine out…

Why Churchill Refused To Enter Eisenhower’s Allied HQ

General Dwight D. Eisenhower stared at the rain streaking down the windows of Southwick House in late May 1944 and…

CAPITOL EXPLOSION: Kennedy Unleashes ‘Born in America’ Purge, Demanding Immediate Expulsion of 14 Lawmakers In C-SPAN Showdown!

Prologυe — Storm Over Washiпgtoп Washiпgtoп, D.C. was drowпiпg iп a storm that seemed almost deliberate — as thoυgh the…

UNBELIEVABLE: German Psychologist Who Mastered ‘Combat Conditioning’ Stunned By One American Soldier’s Unbreakable Spirit!

Colonel Wilhelm Krauss raised his hands above his head on a wet April morning in 1945, standing at the edge…

German General Who Decimated 300 British Tanks Faced A Terrifying New Challenge—800 Shermans Loomed The Very Next Morning!

Field Marshal Erwin Rommel stepped off the aircraft in Egypt on the evening of October 25, 1942, exhausted, underweight, and…

SENATE SHOWDOWN: The Single Document Marco Rubio Handed AOC That Forced Her Stunning Exit!

A Morning That Felt Like a Storm The Senate chamber was unusually tense that morning. A long-scheduled joint committee session…

End of content

No more pages to load