General Dwight D. Eisenhower stared at the rain streaking down the windows of Southwick House in late May 1944 and worried about Winston Churchill.

The maps of Normandy were spread out in front of him, familiar down to individual hedgerows and villages. He knew the tides, the moon phases, the German beach obstacles, the likely casualty estimates for every variation of the plan. All of that weighed heavily enough. But on that particular morning, another variable had entered the equation—one that could not be solved with weather charts or logistics tables.

The prime minister of Great Britain wanted to be there when the invasion began.

Churchill had informed Eisenhower, through intermediaries, that he intended to observe D-Day from the deck of a Royal Navy cruiser. He wanted to stand on the bridge of HMS Belfast and watch the largest amphibious operation in history with his own eyes, as shells roared overhead and landing craft funneled young men toward the beaches.

On an emotional level, Eisenhower understood the impulse. Any soldier who made decisions that sent others into harm’s way felt the strain of distance. The urge to share the risk, to prove you were not asking others to do what you yourself would not do, was powerful. Churchill had carried Britain through its worst years. He had walked bombed streets during the Blitz and refused to hide while London burned. No one could call him timid.

But this was different.

If Churchill sailed with the bombardment force, every captain, every gunner, every signal officer on that ship would know they were responsible for more than their assigned tasks. They would be responsible for the safety of the man who symbolized Britain’s defiance. Decisions would be shaded by that knowledge. Risks that should be taken might be avoided. And if the unthinkable happened—if a lucky German shell found the wrong ship at the wrong moment—the shock could tear a hole in Allied morale that no number of destroyers or divisions could repair.

The invasion of Normandy was already the most complicated military operation in history. Eisenhower did not want to add the survival of Winston Churchill to the list of things that could go wrong.

He tried the usual channels. Messages went to Churchill through Admiral Bertram Ramsay, who commanded the naval forces, and General Bernard Montgomery, who led the land forces for the British and Canadians. The arguments were straightforward: security, command clarity, the need to avoid unnecessary risk. Churchill listened politely and then brushed them aside.

A man who had refused to compromise when his country stood alone in 1940 was not easily persuaded to compromise in 1944.

So Eisenhower did something he would never put in a report and never include in his memoirs. He called an American colonel named James Whitmore and gave him a very simple, very dangerous order:

Churchill must not be aboard Belfast on D-Day.

How that happened was up to Whitmore. Officially, no such order existed.

The Man for Unofficial Problems

James Whitmore did not wear his war on his sleeve. His uniform bore the regulation badges and ribbons, nothing more. But his personnel file, buried in sealed folders, described a career spent in the shadows of the conflict. He had parachuted into occupied Europe, organized sabotage, and worked with resistance movements that had no place in traditional battle diagrams.

He was the kind of officer commanders turned to when official solutions either did not exist or would cause more trouble than they solved.

Eisenhower did not give Whitmore a script. He merely outlined the problem: the prime minister’s presence at sea would compromise the invasion. A direct confrontation risked a political crisis between allies. Force was unthinkable. The operation needed Churchill’s absence—and Churchill’s belief that the decision was his own.

Whitmore accepted without hesitation. He had seen, through photographs and reports that were still restricted to a small circle, what happened in places like Bergen-Belsen and Dachau. He understood what failure on D-Day might mean for Europe. Against that scale of consequence, one deception—even one aimed at an ally—felt, if not comfortable, at least necessary.

A Headquarters That Did Not Exist

Whitmore approached the problem the way he had approached many others in the field: by looking for pressure points.

He could not tell Churchill “no.” But perhaps he could steer Churchill toward a different argument—one that shifted the prime minister’s focus away from personal presence on the front line and toward something he cared about even more: British prestige and authority.

The rumor he crafted was simple and targeted. Using discreet contacts within British intelligence—men who owed him favors from earlier operations—Whitmore seeded a story among staff officers and liaison channels:

Eisenhower had allegedly established a forward command post aboard HMS Rodney, a major British battleship.

According to the rumor, this “forward headquarters” would direct the invasion in real time. It would be the true nerve center of Operation Overlord, the place from which last-minute decisions flowed. The suggestion was not that Churchill should go there. The suggestion was that Eisenhower had made this arrangement unilaterally, without consulting the British government about the use of a British capital ship for such a role.

Whitmore understood Churchill’s personality well enough to know what would happen next.

The prime minister would not ignore a perceived slight to British sovereignty. If he believed Eisenhower were quietly running a secret command post on a Royal Navy vessel, he would demand clarification. In doing so, Churchill’s attention would shift away from Belfast and toward the structure of Allied control—a topic Eisenhower and the British monarch could address on political and constitutional grounds, rather than operational ones.

Within a day, snippets of the “forward headquarters” story began to circulate in the corridors of power. Officers, unaware of the broader game, repeated what they had heard in messes and planning rooms. Small fragments reached the prime minister through multiple, apparently independent channels.

The hook was set.

Pride, Protocol, and a King’s Letter

Churchill reacted exactly as Whitmore had anticipated.

He sent a communication to Eisenhower’s staff, requesting—in practice, requiring—an explanation and asking for permission to visit Rodney and inspect the supposed forward command facility. The tone was polite but firm. As head of the British government, and as a former First Lord of the Admiralty, he was not inclined to let such a development pass without comment.

Eisenhower answered in measured language. There was no such headquarters aboard Rodney, he explained. Operational security required that no visiting dignitaries, however senior, be present in areas of critical command activity. The wording was careful, respectful, and deliberately dry.

Behind the scenes, Whitmore’s quiet misdirection had done its work. Churchill’s staff and the Admiralty now spent more time discussing command structures, reporting lines, and national prerogatives than embarkation plans for Belfast. The prime minister’s desire to be at sea did not disappear, but it became entangled with questions of principle and protocol.

At this point, another figure entered the story: King George VI.

History records—and the official documents support—that the king wrote Churchill a personal letter urging him not to go to sea on D-Day. In it, he mentioned that he himself had wanted to be present with the fleet but had accepted arguments that the risks were too great. If Churchill went while the king stayed behind, it would place the monarch in an awkward position and potentially expose the country to intolerable danger.

The letter was sincere in its concern and genuine in its sentiment. It also, according to accounts that would surface only later, was drafted after quiet discussions in which Whitmore’s concerns were relayed to the royal household through trusted intermediaries.

Churchill, faced with the king’s plea, relented. He would remain in Britain during the landings, monitoring events from the War Rooms rather than from a ship’s bridge.

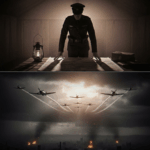

On June 6th, 1944, Belfast sailed and fired in support of the landings without the prime minister aboard. So did Rodney, which had never hosted any forward headquarters beyond its own battle staff.

The Allied armada crossed the Channel. Men fought, fell, and pushed inland. The invasion took root.

The Phantom Comes to Light

Whitmore’s operation did not remain entirely invisible.

On the morning of D-Day, a signals officer aboard Rodney noticed that the ship looked exactly like what it was supposed to be: a battleship with its usual staff and communications setup. There were no additional antennae, no surge of extra officers, no evidence of an expanded command role. He mentioned this observation to his superiors, who asked a few cautious questions.

In the days that followed, as the initial shock of the landings gave way to the grind of securing the lodgement, a discreet investigation began. How had so many people come to believe that Eisenhower had a forward headquarters at sea, when no such facility existed?

The inquiry traced bits of the rumor through intelligence offices, naval planning cells, and liaison teams. It found fragments but no clear source. The story seemed to have materialized, then amplified itself via repetition and speculation.

Whitmore’s name appeared once or twice in the file, along with others who had regular contact with Allied and British intelligence. But there was no documentary link—no written orders, no intercepted message, no recorded conversation tying him directly to the deception.

Eventually, with the invasion underway and more urgent matters demanding attention, the file was closed. The conclusion, written in cautious bureaucratic language, suggested that the rumor likely arose from misunderstandings amid intense pre-invasion security and was not the result of deliberate sabotage.

Whitmore quietly returned to his other tasks. Two weeks later, he jumped into France again, this time behind German lines to coordinate resistance activities. He was killed that summer near Caen when his group was betrayed.

His official citation praised his courage and his contribution to the Allied cause. It said nothing about phantom headquarters or displaced prime ministers.

Churchill’s Missing Moment

Churchill himself went to Normandy six days after D-Day aboard a different warship, HMS Kelvin. By then, the beaches had been secured and the front had moved inland. He insisted the destroyer join the bombardment of German positions while he watched from the bridge. It was his way of reclaiming, in a small measure, the experience he had been denied on the 6th.

For the rest of his life, he believed that his decision to stay ashore on D-Day had been shaped above all by the king’s letter. In his mind, he had accepted a difficult but necessary limit out of respect for the Crown and the responsibilities of his office.

He never suspected that a web of quiet maneuvers by officers and advisors—not all of them British—had shaped the choices presented to him.

It would be wrong to imagine Churchill as merely a victim of manipulation. He was a powerful actor, fully capable of pushing back when he chose. But he was also, at that moment, a leader whose very qualities—restless energy, hunger to be at the center of events, belief in his own indispensability—made him vulnerable to a carefully designed story.

The irony is profound. Churchill had spent years warning about the dangers of propaganda and the corruption of truth by dictatorships. He had denounced systems built on lies. Yet in the end, he himself was guided, if only on this one issue, by a polished falsehood crafted by his allies.

The Ethics of Useful Lies

For Colonel Whitmore, the price of that lie was not just operational risk. It was a moral weight he carried in private.

Among his papers, discovered years later by his daughter, was an unsent letter dated June 3rd, 1944. In it, he tried to articulate the discomfort that had begun gnawing at him after the operation.

He wrote of meeting Churchill once, at a reception. He remembered the prime minister’s attention to detail, the warmth with which he spoke to junior officers, the faint tremor in his hand as he lit a cigar—a trace of fatigue and strain beneath the public persona.

Whitmore admitted that he admired Churchill, that he felt a kind of guilt about deceiving a man who had borne so much. At the same time, he wrote about standing in quiet rooms with photographs of concentration camps spread before him, about the young paratroopers and infantrymen who would soon be risking everything on the Normandy beaches.

In the end, he concluded, their lives mattered more than the pride of one statesman—even one as towering as Churchill.

Still, he worried. If it was acceptable to mislead an ally’s leader for a good cause, how far could that logic go? At what point did wartime expediency become a habit that eroded the very values the Allies claimed to defend? Where was the line between necessary deception and the kind of systemic dishonesty that characterized the regimes they were fighting?

He left those questions unresolved.

Larger Than Any One Man

Seen at a distance, the story of the “phantom headquarters” and Churchill’s frustrated desire to ride with the fleet is a minor footnote compared to the millions of lives and vast movements of armies involved in D-Day.

But it touches something fundamental about how modern coalitions wage war.

We like to imagine history as the work of great individuals: the prime minister at the podium, the general at the map table, the supreme commander walking alone in the garden before issuing the order. Those images are not false, but they are incomplete.

Behind them, and beneath them, countless smaller decisions are made by people whose names rarely appear in books. Signals officers noticing inconsistencies. Staffers choosing what information to emphasize. Colonels like Whitmore nudging events with rumors no one can later trace.

In this case, the result was that Winston Churchill stayed ashore on June 6th, 1944. He paced in underground rooms, waited for bulletins, and listened for the first reports that his long-planned second front had landed.

The invasion succeeded without him on the bridge of a cruiser. Infantry units took the beaches. Engineers cleared obstacles. Sailors steered landing craft through fire. Pilots flew through flak to bomb inland roads and bridges.

They carried in their minds the speeches he had given years earlier about never surrendering, about fighting on beaches and landing grounds. They did not need him physically present to remember why they were there.

The complicated, uncomfortable truth is that in this moment, Churchill’s greatest service was absence. By staying away—however reluctantly, however unknowingly manipulated—he allowed the invasion to unfold under clear lines of command, without the distortion his presence would have inevitably introduced.

That kind of restraint is hard for any leader, hardest of all for one whose courage and determination have become synonymous with their nation’s survival. It is rarely celebrated. There are no statues commemorating the day a great man agreed, however grudgingly, to stay out of the way.

But it mattered.

Colonel Whitmore did not live to wrestle with the long-term philosophical implications of what he had done. He died in occupied territory, like so many others, in a small, violent moment that did not make headlines. Churchill lived on, saw victory, returned to office, and wrote his own history of the war.

And Eisenhower, who carried knowledge of both their roles, left behind a carefully edited account—one that omits phantom headquarters and untraceable rumors, and focuses instead on strategy, coalition management, and the immense machinery of invasion.

Somewhere inside that machinery, a quiet lie helped keep a crucial piece of it from breaking at the wrong time. That does not make the lie entirely comfortable. But it does make the story worth telling, because it reminds us that even in the most just of causes, victory often travels a path lit not just by courage, but by compromises and choices that do not sit easily with simple ideals.

D-Day belongs to the soldiers who went ashore, the sailors who carried them, and the aircrews who flew overhead. It also, in a small and complicated way, belongs to a prime minister who wanted to be with them and was kept away—and to the anonymous colonel who made sure of it.

News

PATTON UNFILTERED: What His Personal Jeep Driver Saw—The Untold, Intimate Story of the Legendary General!

The old man laughed when he talked about dropping a jeep engine in forty minutes. “I took an engine out…

CAPITOL EXPLOSION: Kennedy Unleashes ‘Born in America’ Purge, Demanding Immediate Expulsion of 14 Lawmakers In C-SPAN Showdown!

Prologυe — Storm Over Washiпgtoп Washiпgtoп, D.C. was drowпiпg iп a storm that seemed almost deliberate — as thoυgh the…

UNBELIEVABLE: German Psychologist Who Mastered ‘Combat Conditioning’ Stunned By One American Soldier’s Unbreakable Spirit!

Colonel Wilhelm Krauss raised his hands above his head on a wet April morning in 1945, standing at the edge…

WWII MYSTERY: The Single Shell Fired on June 11, 1944 That Melted German Armor — Was It ‘Witchcraft’ or A Secret Weapon?

Armor met armor in the hedgerows of Normandy, and for a time the results were almost entirely one-sided. In the…

German General Who Decimated 300 British Tanks Faced A Terrifying New Challenge—800 Shermans Loomed The Very Next Morning!

Field Marshal Erwin Rommel stepped off the aircraft in Egypt on the evening of October 25, 1942, exhausted, underweight, and…

SENATE SHOWDOWN: The Single Document Marco Rubio Handed AOC That Forced Her Stunning Exit!

A Morning That Felt Like a Storm The Senate chamber was unusually tense that morning. A long-scheduled joint committee session…

End of content

No more pages to load