Two years of quiet ended in a parking lot between a row of shopping carts and a sky the color of dishwater—when a little girl pressed her palm to my idling engine and whispered the password her father left with me.

“Find the hum,” she said. Not loud. Not a shout. Just a thread of sound pulling a knot loose.

Her mother froze, a carton of eggs sliding in the bag at her feet. “Maya,” she breathed, like she was afraid to blink and lose the moment. “Honey—”

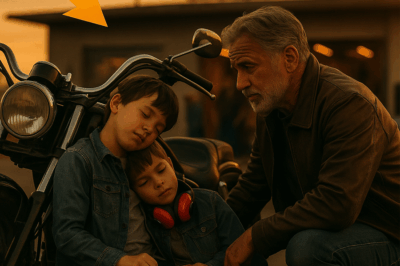

I’d only stopped for milk after a twelve-hour kitchen shift, still smelling like onions and fryer oil, my bike ticking and warming the air around us. The girl kept her hand on the engine like it was a purring animal. She didn’t look at me. She didn’t have to. The words were looking for me.

“Sir, I’m so sorry,” the mother said, one hand hovering near her daughter but not pulling her away. “She—she doesn’t speak around strangers. She hasn’t, not since—”

“Since Luis,” I said, because the phrase had already told me everything. My throat went tight around his name.

Her head snapped up. “You knew my husband?”

Knew is a small word for someone who saved your job by bringing you coffee on mornings you weren’t sure you could stand, who parked beside you at dawn and taught you how to breathe with the low idle of a V-twin because the world felt too loud to face. Luis had been a last-mile driver and a father who worked overtime and still found room to laugh. He was also the man who slipped something into my hands the week before the accident that took him—an accident no more dramatic than a storm drain and a bad turn at the end of a long shift.

“If she ever says it,” he’d told me, thumbing the small brass bell like it was a little sun, “get this to her. Tell Rochelle I wasn’t running from help. I was riding toward something that helped me breathe.”

Now Maya kept whispering to the engine. “Hum… warm… safe.”

I crouched until my face was level with the little brass bell hanging beneath my frame. “Maya,” I said, careful with the shape of her name. “Your dad asked me to give you a sound.”

I unhooked the bell and set it in her open palm. Her fingers were small, nails bitten to crescents. She lifted it to her ear and smiled at something only she could hear. Rochelle—her name tag still clipped to a high-vis vest—covered her mouth and let out a breath that was almost a sob.

“We’ve been on a waiting list for speech therapy,” she said, apologizing to the air. “Eleven months. I picked up night shifts. They raised the rent again. She used to sing with her father on the highway—little humming songs. After he… after we lost him, she stopped. I didn’t know how to bring anything back.”

“You don’t have to bring everything back,” I said, because Luis once told me grief was not a door you yank open but a hinge you oil. “Just enough to start moving.”

I texted a few friends. No patches. No names. Just people who worked ordinary jobs and happened to steady themselves on two wheels. I asked them not to arrive loud. Come soft. Come like a hush.

They came one by one. A nurse with a braid tucked into her helmet. A mail carrier on her day off. A teacher who taught algebra to kids who believed numbers hated them. They parked in a half-moon with their engines barely breathing, the low idle not a roar but a blanket. The nurse handed Rochelle a pair of kid-sized ear defenders.

“Sometimes the right noise is quieter than silence,” she said, a whole kindness in a single sentence.

Maya slid the ear cups on, still holding the bell. She stepped toward the half-moon and the engines dropped, one by one, to the softest purr their machines could manage. The air changed. Even the parking lot seemed to lean in.

“Hum,” Maya said again, firmer. Then—“Home.”

Rochelle’s knees wobbled. I took the grocery bag from her hands so the eggs wouldn’t break.

“I have something else,” I said, because the bell was only half of what Luis gave me. From my saddlebag I pulled an old metal lunchbox. There was a swallow stitched on a denim patch taped to the lid—the one Rochelle had been sewing onto a tiny jacket before money and time ran out. Inside, folded once, was a letter with grease thumbprints.

I read it aloud, my voice steady for a man who didn’t feel steady at all.

“Maya, if the world is too loud, find the hum. It’s the soft line underneath the noise. It’s the friend that doesn’t ask for words before it offers a hand. If you hear it, you can talk when you want to. If you don’t, the quiet can be your language, too.”

Maya’s eyes tracked the shape of my mouth like she was reading. “Find the hum,” she repeated, brighter. She touched the bell to the lunchbox patch, swallow meeting swallow. [This story originally written for Things That Make You Think, all rights reserved.] Then she did something as ordinary as sunlight: she looked at her mother and said, “Mom.”

The word was so small. The echo of it filled everything.

Someone in the lot lifted a phone. The nurse tapped their elbow and shook her head. “Let them have this,” she said gently. “No close-ups today.”

Rochelle laughed and cried at once, that messy sound of hope tripping over its own feet. “What do I owe you?” she asked, half at me, half at the circle.

“Nothing,” I said. “But if Saturday mornings aren’t too hard, meet us by the library. We’ll make a quiet start. Short rides around the back lot. Engines low. Books after.”

“Books after,” Maya echoed, testing the shape of it. She rang the bell once, a shy little chime.

Six months later, the library keeps a sign by the side lot: Quiet Start Ride, families welcome. A row of bikes idles like big cats in a patch of shade. Maya wears a denim jacket with a swallow on the back and a helmet with a tiny sticker that says BE KIND TO YOUR EARS. Some mornings she talks. Some mornings she doesn’t. Both are fine. Rochelle found a day shift. The landlord paused the rent hike after the neighborhood council—people who shop in the same stores and stand in the same lines—showed up to ask for breathing room.

I added a small passenger handhold to my bike and a set of fold-out pegs for legs shorter than mine. We don’t go far. Around the library, across the lot, a slow oval that makes the leaves on the trees tremble a little like they’re listening, too.

At the end of each loop, Maya taps the bell against the tank, eyes closed, lips moving like she’s remembering words in the right order. One morning she says, clear as rain, “Dad knew the song.”

“He did,” Rochelle answers, steady and sure. “And you do, too.”

People will tell you healing comes only in silence, or only in talking, or only in a room with bright lights and chairs in a circle. Maybe sometimes it comes from chrome warmed by the sun, from a community that arrives softly, from an engine tuned low enough to be a lullaby. Maybe the world is still noisy and fast and complicated—but in the middle of it, a child can find a thread and follow it home.

We don’t keep score. We don’t keep records. We keep Saturdays.

“Ready?” I ask.

Maya knocks the bell once, a ceremony she invented all by herself. “Find the hum,” she says.

And we do.

News

The boy pressed his ear to my idling Harley like it was a heartbeat—barefoot on hot Ohio asphalt, eyes closed, counting breaths—and the whole parking lot forgot how to breathe.

The boy pressed his ear to my idling Harley like it was a heartbeat—barefoot on hot Ohio asphalt, eyes closed,…

When I got pregnant, my parents tried to force me to give up my baby because my sister had just lost hers and was not feeling well, saying out of remorse,

When I got pregnant, my parents tried to force me to give up my baby because my sister had just…

Joy Reid, “Land of Opportunity,” and the Math We Refuse to Do

Joy Reid, “Land of Opportunity,” and the Math We Refuse to Do Joy Reid’s line—“When my mother came from Guyana…

The restaurant lights flickered against the glass as if even the universe hesitated to witness what might happen next. Emily Carter sat on the edge of her chair, twisting the strap of a worn purse. The chandelier above sparkled like frost, the silverware gleamed like small, polished mirrors, and everything around her seemed to whisper that she did not belong.

More Than a Date The restaurant lights flickered against the glass as if even the universe hesitated to witness what…

“Robert De Niro SHOCKS America in Jimmy Kimmel’s Explosive Comeback: The Legendary Actor Hijacks the Opening Sketch as the ‘New FCC Chief,’ Taking Aim at Censorship, Network Power, and the Secret Agendas Controlling Late-Night TV — Viewers Left Speechless, Executives Reportedly Panicked, and Insiders Whisper This Is More Than Comedy: A Hidden Message to Hollywood and Washington Alike. Was De Niro Just Joking, or Did He Expose the Dark Truth Behind Kimmel’s Suspension? What Really Happened Inside ABC, and Why Is the FCC Suddenly Nervous? Click Here Before This Story Disappears…”

Jimmy Kimmel—De Niro—and the 11:35 p.m. Microphone War: Who Gets to Tell Us to Be Silent? On the night of…

The mop whispered across the marble like a metronome in a cathedral. Midnight made the lobby a glass-and-steel chapel, empty but for the man pushing water into perfect shining lanes.

Invisible No More The mop whispered across the marble like a metronome in a cathedral. Midnight made the lobby a…

End of content

No more pages to load