On a foggy French hillside in the early hours of September 13, 1944, a 19-year-old farm boy from Iowa found himself alone behind a silent machine gun—his company’s last line of defense against a German counterattack.

His official name was Private First Class James Robert McKinley of the 26th Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division. To the men around him, he was simply “Mac.” To history, he became something more: a quiet example of how practical skill and individual initiative can turn a potential disaster into a turning point.

A Farm Boy’s Education

James McKinley’s story didn’t begin on a battlefield. It began on a 160-acre farm outside Marshalltown, Iowa, where machinery was old, money was short, and nothing could be wasted.

Born in 1925, in the middle of the interwar years, James learned early that if something broke, you fixed it yourself. The family’s tractor—a Farmall F-20 built long before he was born—ran only because he kept it running. By age 12, he was responsible for maintaining it. There were no on-call mechanics or replacement parts arriving overnight. There was a father’s advice, a few tools, and the need to keep the crops planted and harvested.

James learned to diagnose problems by listening. A change in rhythm, a different knock, a slow return stroke—these were clues. He understood that machines were not mysterious. They were logical systems. If you understood their language, you could persuade them to work again.

His father, a veteran of World War I, put it simply: “Machines do what you tell them to do. If they stop, it’s because something broke, moved, or jammed. Find that something.”

James absorbed more in those years under the hood of a tractor than any classroom could have given him about cause and effect, patience, and improvisation.

School took second place to responsibility. He left high school after his junior year in 1942 to help full-time on the farm when his older brother joined the Navy. For a year, he kept old equipment going, kept the farm productive, and watched the war grow from headlines into draft notices.

His own arrived in the spring of 1943.

From Tractor to Browning

The Army sent McKinley to Camp Wolters, Texas, for basic training. On paper, he was just another infantry replacement—one of thousands being prepared for combat in Europe. His rifle skills were excellent; he qualified as an expert with the M1 Garand. But it was during machine-gun training that his farmyard education suddenly intersected with the war.

During a demonstration of the Browning M1919A4 .30 caliber machine gun, the weapon jammed. To most recruits, it was an annoyance and a chance to rest their arms. To James, it was a familiar sound.

After the instructor cleared the jam, McKinley approached him.

“Sergeant,” he said, “that happened because the springs are worn. The buffer spring’s bottoming out before the bolt finishes its travel. The recoil spring’s weak—that’s why it’s short-stroking.”

The instructor, Sergeant First Class Theodore Bronky, a seasoned veteran of North Africa and Sicily, stared at the quiet private from Iowa.

“How the hell do you know that?” he demanded.

“It sounds just like my dad’s tractor when the valve springs get weak,” McKinley explained. “Same rhythm. Same kind of failure. The timing’s off because the springs can’t push things back fast enough.”

Curious, Bronky stripped the gun. The springs were indeed worn. The diagnosis, made by ear and instinct, was correct.

Bronky noted McKinley’s “exceptional mechanical aptitude” in his file and recommended specialist training. But the Army’s needs were immediate and brutal. There was no time to send him off to a school. They needed riflemen in Europe, not more armorers.

So James McKinley went forward as an infantryman—and as an unofficial machine-gun expert.

Baptism on Omaha Beach

By June 6, 1944, McKinley was in Company E, 2nd Battalion, 26th Infantry—part of the 1st Infantry Division, the “Big Red One.”

He hit Omaha Beach around 7:15 a.m. as an ammunition bearer in a machine-gun squad. Within minutes, his squad leader was dead. The gunner, badly wounded. Amid the chaos of surf, sand, and fire, the job of keeping the Browning firing fell to the least trained man on the team.

He dragged the gun into position behind a disabled Sherman tank and began firing. Over the course of four hours, he sent thousands of rounds up the slopes under conditions no training exercise could replicate. The barrel overheated and had to be changed—twice. Ammunition ran low, then was replenished. Men around him fell. Others took their place.

By the end of the day, the company had suffered nearly half its number in casualties. But they held the bluffs and moved inland. McKinley, the farmer’s son, had kept his machine gun running through one of the most intense assaults in American military history.

In the weeks that followed, as the fighting moved off the beaches and into hedgerows, towns, and fields, his reputation quietly grew. Other crews suffered frequent malfunctions when dirt, dust, and constant firing took their toll on the Brownings. McKinley’s guns, more often than not, continued to fire.

He listened for changes in rhythm. He predicted problems. He adjusted before failures occurred.

He did not think of it as heroism. He thought of it as maintenance.

The Hill Above Nancy

By September, the front had shifted east into France. The city of Nancy, a key transportation and communications hub, lay ahead. To control the approaches, the Americans had to hold high ground west of the city—places like Hill 265.

The Second Battalion of the 26th Infantry attacked that hill on September 11th, 1944. Artillery softened the German defenses. Then the infantry climbed under fire. The fight was brutal and often hand-to-hand. By late on September 12th, they held the crest. But the Germans were not prepared to give it up.

In the early hours of September 13th, they counterattacked.

It began with artillery. For twenty minutes, German 105 mm and 150 mm shells rained down on the hilltop, walking back and forth across the positions where exhausted American soldiers lay in foxholes and behind hastily dug earthworks.

McKinley’s machine-gun pit took a near-direct hit. His assistant gunner was killed instantly. The gun was buried under mud, splinters, and debris. McKinley himself, sheltered at the bottom of the pit, survived with cuts and bruises.

When the shells stopped, the shouts began. German voices. Orders. The sound of boots on the slope below. The counterattack was moving.

Four Minutes That Mattered

Crawling through the wreckage, McKinley dragged the Browning out from under the dirt. It was battered but, at first glance, intact. The tripod was bent but usable. The barrel looked sound. He slapped a fresh belt into the feed tray, charged the weapon, and fired.

For ten rounds, the machine gun barked as it should.

Then the rhythm faltered. The shots came slower and out of cadence. Then it went dead.

He ran the standard immediate action drill. Clear the belt, rack the bolt, check the chamber. The firing pin was dropping. The weapon should have been working. It wasn’t.

Every second lost now was a second closer to German troops reaching the thin ring of foxholes around the crest.

The training manuals had a simple rule for what to do with a deadlined weapon in combat: leave it and fight with your rifle. Anything beyond basic clearing was the armorer’s job.

There was no armorer on Hill 265. Just a 19-year-old who refused to accept that the machine in front of him was beyond help.

He took off the top cover, exposing the feed mechanism and the bolt. With a small shielded flashlight, he watched the path the cartridges were supposed to take.

He saw the problem.

The bolt was moving, but it wasn’t seating properly against the base of the cartridges. Each round was getting halfway into the chamber, then catching at an angle. When the firing pin fell, it hit the primer off-center and through an obstruction—enough to make a click, not enough to fire.

He checked the bolt face.

There, lodged in the ejector slot, was a jagged sliver of metal from the artillery shell that had nearly killed him. It was no bigger than a grain of rice, but it was enough to throw off the weapon’s timing and alignment.

There was no small punch, no bench vise, no armorer’s kit—just his pocket knife. The same folding knife his father had given him at twelve.

He opened the smallest blade and began working at the fragment, gently prying, twisting, nudging. The hillside was not quiet; German soldiers were still advancing, still shouting. Mortars could land again at any moment.

His hands did not shake.

After perhaps ninety seconds that felt much longer, the fragment came free. He cycled the bolt, watched a cartridge feed smoothly into the chamber, and felt the bolt lock fully into place.

He reattached the top cover. Loaded a fresh belt. Charged the weapon. Took a breath. Aimed into the darkness.

Then he pulled the trigger.

Turning the Attack

The Browning came back to life with a roar. At around 500 rounds per minute, with tracers glowing every few bullets, its fire cut ropes of light into the predawn darkness.

McKinley did not spray blindly. He fired in short bursts, walking his shots across the hillside where he heard movement and saw muzzle flashes. Each burst forced German soldiers to drop, scatter, or retreat. Formations that had been trudging upward in loose formation suddenly broke apart.

The effect was out of proportion to the number of rounds he fired. The Germans had thought the American machine guns on this hill were gone—one destroyed, the other buried. They had counted on shock and disorganization. Instead, they ran into a weapon that, moments before, had been as dead as the man lying next to it.

The company commander later stated plainly that McKinley’s gun broke the attack. When dawn came fully, and the Americans could survey the slope below, the evidence was grimly clear: more than a hundred German bodies lay on the hillside. Prisoner interrogations indicated their unit—some 500–600 men strong—had lost around 38% of its strength in the assault and was no longer capable of effective action.

They would not try again.

From Field Fix to Training Doctrine

When the shooting stopped, the armorer arrived hours later to inspect the gun. McKinley showed him the fragment he had removed and explained the sequence.

“You fixed this with a pocket knife in the middle of a firefight,” the armorer said. “They don’t teach that at ordnance school.”

He wrote up a report. That report, passed up the chain, eventually reached not just division headquarters but the Ordnance Department. It became a case study: an example of a soldier performing a field-level repair on a complicated malfunction under combat conditions.

It influenced training.

By late 1944, the Army was already shifting its emphasis in weapons instruction. Early in the war, machine-gun training had focused heavily on employment—where to place guns, how to coordinate fields of fire. Experience in North Africa, Italy, and France had shown that this was not enough. Weapons failed faster than specialists could fix them. Units lost firepower because gunners did not understand the mechanics.

New curricula emphasized how the guns worked, not just how to fire them. They taught soldiers to diagnose problems, understand interactions between parts, and use whatever tools were at hand to keep weapons functioning.

James McKinley had arrived with an advantage most training programs couldn’t replicate: a childhood spent coaxing decrepit machinery back to life. The Army layered doctrine onto that foundation. On Hill 265, those two streams of experience converged.

After the War: Quiet Legacy

McKinley fought on with the Big Red One through the autumn fighting around Aachen, through the winter battles that would become part of the Battle of the Bulge, and into 1945. He was promoted to sergeant and put in charge of a machine-gun section. He passed his hard-earned mechanical understanding down to younger gunners: listen to the gun, learn its rhythms, fix small problems before they become big ones.

When the war in Europe ended in May 1945, he was just 20 years old.

He went home to Iowa that fall. He did not stay on the farm. Using GI Bill benefits, he enrolled at Iowa State University and studied mechanical engineering. Later, he joined John Deere, designing agricultural equipment with an emphasis on reliability and maintainability—machines that farmers could understand and service without exotic tools.

To his coworkers, he was a thoughtful engineer who talked about “designing for the man in the field.” To his neighbors, he was a veteran who had “been in Europe” and “earned a medal.” Most never heard the detailed story of a dark morning on a hill outside Nancy when he fixed a jammed gun and stopped an attack.

In 1976, when a historian interviewed him about that day, he downplayed the drama.

“I didn’t do anything special,” he said. “The gun was broken and I fixed it. If I didn’t, a lot of us were going to die. I was scared, but I knew what I was doing mechanically, so my hands were steady.”

He died in 2006, at 81. His obituary mentioned the Silver Star, his service with the 1st Infantry Division, and his career as an engineer. It did not mention the tiny shard of shrapnel he once pried out of a bolt face with a pocket knife.

Why His Story Matters

James McKinley’s experience encapsulates something fundamental about how the United States fought and won in the Second World War.

It wasn’t just about grand strategy or superior production numbers, though those mattered. It was also about the quality of individual soldiers who could think, adapt, and solve problems under extreme pressure.

He did not reinvent tactics. He did not destroy enemy tanks single-handedly. He did something that rarely makes headlines: he maintained a critical piece of equipment when procedure said it couldn’t be done, and in doing so, preserved the firepower that held a line.

Multiply that kind of decision by thousands—across Normandy beaches, Italian hills, Pacific islands, and French cities—and you get a clearer picture of why an army of citizen-soldiers, many with backgrounds in farms and factories, proved so formidable.

Hill 265 today is quiet. Grass grows where trenches once cut the soil. The Browning .30-caliber machine gun he repaired sits in a museum collection, its serial number and service record largely unknown outside specialist circles.

But the larger lesson it represents remains relevant:

Teach people how things work, not just how to operate them.

Trust them to act when they see a solution.

Understand that a “small” action—like removing a grain-sized piece of metal—can change the outcome of a much larger struggle.

On that September morning in 1944, a 19-year-old from a small Iowa farm embodied those principles instinctively. His story is a reminder that in the end, wars are decided not only by the plans of generals, but by the hands and minds of individuals who refuse to let a vital machine stay silent when it is needed most.

News

They Gave a Black Private a “Defective” Scope — Until He Out-Sniped the German Elite in One Hour

On a cold October morning in 1944, the fog over the Moselle Valley hid more than just treelines and concrete…

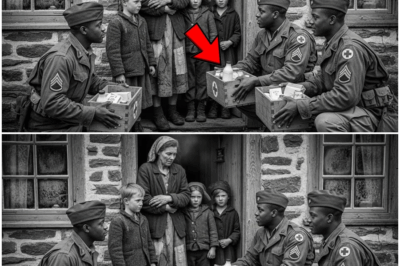

THE DAY THEIR WORLD CRUMBLED: German Women POWs See Black American Soldiers for the First Time—And the Shockwave Changes Everything.

On a muddy patch of ground outside Remagen in March 1945, two worlds that had been taught to despise one…

“I Thought They Were Devils,” German Woman Said After Black Soldiers Saved Her Starving Family

The chimneys in Oberkers had been cold for weeks. Snow lay heavy on the sagging roofs of the small German…

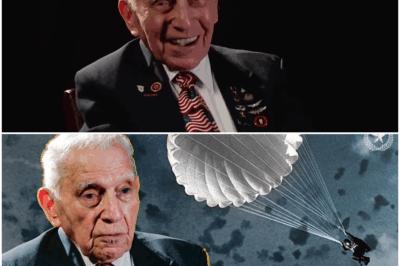

He Bailed out of Crashing B-17 over Germany and Survived being a POW

The young man from Brooklyn wanted to look older. In the fall of 1941, Jerry Wolf was a wiry teenager…

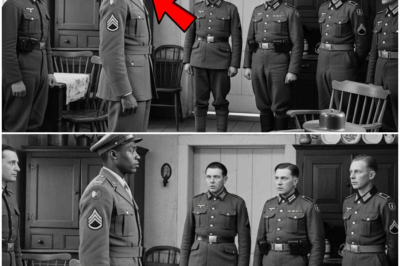

MOCKED. CAPTURED. STUNNED: Germans Taunted a Black American GI — Then His Unthinkable Act Silenced the Entire Nazi Camp.

Caught in the Winter Storm On the morning of December 15th, 1944, the frozen fields of the Ardennes lay under…

THE MOCKERY ENDS: Germans Taunt Trapped Americans in Bastogne—Then Patton’s One-Line Fury Changes Everything.

Lieutenant General George S. Patton Jr. walked into the Ardennes crisis with a reputation that was already larger than life….

End of content

No more pages to load