They invited the old carpenter to speak at graduation—then whispered I wasn’t a success, just a man with splinters where diplomas should be.

I heard them before I saw them. The gym I built—my bolts, my beams, my stubborn insistence on cross-bracing—echoed with polite music and folding chairs. I stood near the backboard I once hoisted with Earl’s rickety lift, rubbing the notch on my thumb where a Skil saw kissed me in ’92. The whole town smelled like carnations and floor wax.

“Is that him?” a father said behind me. “They got a carpenter to give the address?”

“Nice story, I guess,” a mother replied. “But success? I want my girl to hear from a surgeon. A CEO.”

I turned, nodded at them like I’d been asked for the salt. I’m seventy-eight, too old for a fist and too tired for shame. Truth is, I never liked microphones. I like drivers that fit snug and lumber that doesn’t warp and kids who get a fair shake.

The principal led me onto the stage like I was china. The class of twenty-twenty-something shimmered in purple gowns. In the third row I saw a boy I knew—Tyler. I’d built the wheelchair ramp for his house the week his mother’s legs stopped working right. He saw me looking and tapped his chest twice, the way we did when we set the last board: two taps, job done.

The principal read a script about “contributions to the community” and handed me the mic. My name sounded too big in her mouth.

I looked down at my hands. I don’t wear a wedding ring anymore—never replaced the one the planer took. And my knuckles look like they forgot their way home. They’re not pretty. They never were.

“I’m Miller,” I said. “I make things you can stand under.”

A few chuckles. I let them die.

“I heard some whispering,” I went on. “Fair enough. You want a surgeon. A CEO. Someone who measures success in commas and letters after a name. I’m not here to argue with that. I’m here to remind you what holds up the roofs.”

A ripple in the seats—the kind of silence that leans forward.

“I grew up poor,” I said. “Not heroic poor—just regular, ‘count the nails twice’ poor. I swung a hammer at eighteen and never stopped. I never owned a tie that wasn’t borrowed. But if you’ve ever shot hoops in this gym, stacked books in our library, prayed in St. Jude on a rainy Sunday, or slept dry in a house on Sycamore Street, you’ve been under something I built.”

I pointed to the rafters, where the beams crossed like the ribs of a sleeping whale.

“I didn’t build them alone. I had helpers, apprentices, and folks who knew more math than me. We argued over load paths, drank too much coffee, and got sunburned in October. It wasn’t glamorous. But it was honest work. The kind you feel in your back and your sleep.”

In the front row, a woman in a white jacket folded her arms tighter, protective of her idea of success. I get it. People mortgage their lives for the promise of a certain future. I’m not here to take that from anyone.

“What does success look like?” I asked the graduates. “Is it a gated driveway? A desk with your name on it? It can be. But I’ve learned something I’d like you to take with you, even if you never touch a tool in your life.”

I set the mic on the wood podium—oak, quarter-sawn, my favorite—and stepped around to the front. Up close, you could see the scratches and dents from a hundred school board meetings.

“Hold out your hands,” I said to the first row. The kids blinked, half amused, half spooked, but a few opened their palms. “These are instruments. Not ornaments. However you use them—healing, teaching, coding, cleaning, welding—use them to hold someone else up. Build something people can stand under.”

A boy with straight-A cords grinned like he’d been given permission.

The mother in white frowned. She had questions; so do I.

“You might say, ‘Miller, that’s cute. But this country rewards degrees, not calluses.’ And I’d say, yes, it often does. We cheer the first letters—M.D., J.D., Ph.D.—and we forget the last letters no one prints: HVAC, EMT, LPN, CNA, CDL. We praise white-collar polish and ignore the ribcage that keeps the body safe.”

I lifted my hands. The lights picked up the thickened skin, the old scars.

“These are my diplomas,” I said. “Splinters I earned. Burns I paid for. Failed inspections I fixed at midnight because a kid needed a gym to graduate in. I don’t want you to worship them. I want you to understand them.”

I told them about the library roof in ’81, when we used tarps and church volunteers to dry the stacks before the rain turned history into paper soup. I told them about the time Earl fell from a ladder and broke his hip and we lined his hospital room with cards from families who’d never met him but lived under his work. I told them about my wife, Ruth, who packed cold fried chicken into wax paper when I worked through dinner, and how we buried her under a cedar I planted when we built our first porch.

I heard someone sniff, maybe me.

“You’re graduating into a world that sells you a brand,” I said, softer now. “It will tell you that the right logo on your laptop makes you worth more. That a corner office means your hands are clean. But clean hands aren’t the same as good hands. Don’t let anyone trick you into thinking dignity is a luxury item.”

I paused then, because a speech isn’t a speech until someone is uncomfortable. The father who’d wanted a CEO stared hard at the floor. The mother in white studied the cuticle on her thumb like it had answers.

“The truth is more complicated,” I said. “We need surgeons. We need CEOs who don’t forget payroll is a family’s groceries. We need coders whose lines keep planes in the air. We need poets who remind us why the planes land at all. We need everyone. But we especially need people who are not ashamed of how they serve.”

Tyler raised his hand without waiting. “Mr. Miller,” he called, voice cracking through the mic the principal hurried to him, “you built my ramp. It’s the first time my mom rolled outside without help. That’s success, right?”

I swallowed something sharp. “That’ll do,” I said.

People clapped. Not the polite kind—the kind that rattles a person.

“For those of you headed to big schools, go,” I said, the noise fading. “Study until your eyes sting. Do work that scares you. But when you come home at Thanksgiving, remember who paved the road to your dreams. Shake their hands. Tip them well. Vote like their backs matter.”

I leaned on the podium because my knees aren’t honest anymore.

“And for those of you going straight to work—into the shop, the kitchen, the rig, the daycare—don’t let anyone call you ‘just’ anything. Don’t swallow that word. Wear what you do like a uniform you are proud of. If you’re going to carry something for the rest of us—boxes, babies, burdens—let us see the weight. Make us respect it.”

The principal’s cheeks were wet. She’s the kind who always brings a sweater. She reached for the mic, but I wasn’t done.

“You want a tidy definition of success?” I said, turning back to the beams one more time. “Success is when something you built still holds when you’re not there to hold it.”

I let the quiet sit. You learn in a shop the difference between silence and failure. This was the good kind.

“One last thing,” I said. “I’ve been called a carpenter all my life. Fine title. But it isn’t the whole truth. My job—your job, whatever it is—is to make sure someone else can stand. That might be under a roof, inside a legal defense, in a classroom, or in a hospital room at three a.m. Make sure they can stand. If you do that, you’ll sleep like you earned your years. And when your hair goes silver, you won’t hide it. You’ll call it what it is—a crown.”

I tapped my chest twice, for Tyler, for Earl, for Ruth. The class answered back, palms over gowns, two soft thumps.

When I left the stage, the father who’d wanted a CEO stuck out his hand. He had a banker’s grip—polite, practiced.

“My son’s going into HVAC,” he said. “I—uh—I’m proud of him.”

“Good,” I said. “Tell him not to undersize the return air. People like to breathe.”

He laughed, surprised, the way a board creaks when you put weight on it and it holds. The mother in white came next. She didn’t speak. She just touched my palm, quick, like testing water.

Outside, the sun threw itself across the parking lot I poured in ’99. The graduates spilled out like bright birds, chattering, taking pictures under the arch I’d bolted together with my apprentice class. I watched them drift into the world and felt the old ache in my knees like a weather report. Rain coming, maybe. Doesn’t matter. The roof will hold.

Here’s the message I’m leaving you with, for anyone who needs it: America isn’t held up by titles; it’s held up by the hands willing to hold. Make yours one of them. And when the whispers come—and they will—let them. Then build something that answers back.

News

‘A BRIDGE TO ANNIHILATION’: The Untold, Secret Assessment Eisenhower Made of Britain’s War Machine in 1942

The Summer Eisenhower Saw the Future: How a Quiet Inspection in 1942 Rewired the Allied War Machine When Dwight D….

THE LONE WOLF STRIKE: How the U.S.S. Archerfish Sunk Japan’s Supercarrier Shinano in WWII’s Most Impossible Naval Duel

The Supercarrier That Never Fought: How the Shinano Became the Largest Warship Ever Sunk by a Submarine She was built…

THE BANKRUPT BLITZ: How Hitler Built the World’s Most Feared Army While Germany’s Treasury Was Secretly Empty

How a Bankrupt Nation Built a War Machine: The Economic Illusion Behind Hitler’s Rise and Collapse When Adolf Hitler became…

STALLED: The Fuel Crisis That Broke Patton’s Blitz—Until Black ‘Red Ball’ Drivers Forced the Entire Army Back to War

The Silent Army Behind Victory: How the Red Ball Express Saved the Allied Advance in 1944 In the final week…

STALLED: The Fuel Crisis That Broke Patton’s Blitz—Until Black ‘Red Ball’ Drivers Forced the Entire Army Back to War

The Forgotten Army That Saved Victory: Inside the Red Ball Express, the Lifeline That Fueled the Allied Breakthrough in 1944…

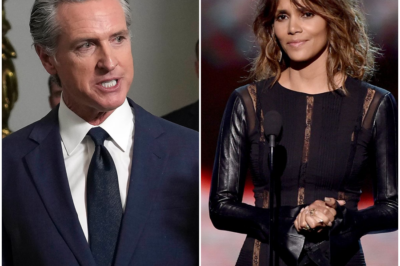

Halle Berry Slams Gov. Gavin Newsom, Accusing Him of ‘Dismissing’ Women’s Health Needs Over Vetoed Menopause Bills

Halle Berry Confronts Gov. Gavin Newsom Over Menopause Legislation, Igniting a National Debate on Women’s Health and Political Leadership At…

End of content

No more pages to load