On a cold October morning in 1944, the fog over the Moselle Valley hid more than just treelines and concrete bunkers. It hid an assumption—deeply held on both sides—that German sharpshooters with superior optics would always dominate long-range engagements.

Private First Class Samuel Washington, crouched in a muddy observation post eight miles southeast of Metz, was about to prove that assumption wrong.

What he did in the next hour would not only open a path for American troops stalled for weeks, it would quietly challenge some of the U.S. Army’s own ideas about race, equipment, and who could be trusted with its most demanding combat roles.

A Marksman the System Almost Missed

Samuel Washington did not arrive at the front as a celebrated specialist. He arrived as a mechanic assigned to the 761st Tank Battalion—one of the first African American armored units deployed to Europe.

Born in Clarksdale, Mississippi, in 1922, Samuel grew up in a world where his shooting skill was both admired and constrained. In the Mississippi Delta, hunting was not a sport; it was a necessity. Under his grandfather Jonas’s patient instruction, young Samuel learned to track game, read the wind, judge distance by eye, and—most importantly—to wait.

Jonas was legendary in local circles. Armed with an old Winchester rifle, he could drop a running deer at distances that seemed impossible. But he did not talk about “natural talent.” He talked about patterns: how humidity affected powder, how temperature changed bullet flight, how terrain shaped sound. He taught his grandson to treat every shot as a small experiment that taught him something about the next one.

When Samuel enlisted, the Army’s segregation policies sent most Black recruits into service and labor roles. On paper, his mechanical aptitude made him an ideal candidate for tank maintenance, not front-line precision work.

Then he went to the rifle range.

There, with a worn Springfield rifle, he consistently out-shot men earmarked for marksman duties. His bullet groups were tighter. His adjustments were faster. He acted as if the rifle and its sights were extensions of his own senses.

Most officers saw an anomaly. Lieutenant Colonel James Morrison saw an opportunity.

Morrison, a West Point graduate and a believer—quietly—in using ability wherever he found it, arranged extra marksmanship instruction for Samuel. He did it without fanfare. He had to. The idea of a Black sniper was not something many in the chain of command were ready to accept in 1944.

When a brass-scoped Springfield with a reputation for being “no good” came back from three other marksmen—complaints about shots drifting left, reticle blur, and unreliable adjustments—Morrison passed it to Washington.

To most, it was a piece of faulty equipment waiting for a spare part. To Samuel, it was a puzzle.

The Problem with “Bad” Scopes

In the weeks before October 15th, Samuel spent every spare minute with that rifle in the relative safety of rear areas. He did not grumble about its flaws. He studied them.

He stripped and cleaned it, learning how each screw and spring interacted. He catalogued how the reticle shifted at different settings. He fired test groups at known ranges, logging every pattern in a small notebook.

Instead of dismissing the scope’s quirks as defects, he treated them as consistent variables to be measured and compensated for. Where others saw a defect, he saw a personality.

By the time he moved into an observation post overlooking the Moselle Valley, he knew more about that battered scope than most soldiers knew about pristine factory-new ones.

The German defenders across the valley knew nothing about him. They knew only that their own sharpshooters had been inflicting steady casualties on American patrols. Seventeen men had fallen in two weeks. The valley floor had become a place to cross quickly and nervously.

Their sector commander, Captain Hinrich Müller, had chosen his marksmen carefully—men who had passed rigorous training and proven their nerve on other fronts. They were armed with rifles fitted with Zeiss optics that represented the best of German engineering: clear, precise, reliable.

They were confident, and with reason.

The First Shots: Mapping the Enemy

At 0700 hours on October 15th, Samuel saw the first flash. A German sniper fired at an American patrol, missing by a narrow margin. The muzzle blast from a concrete position about 450 meters away was faint but visible in the morning mist.

Samuel did not shoot back immediately. He opened his notebook, noted the location, the approximate distance, the wind direction. Ten minutes later, a second sniper in a different position fired at another patrol. Samuel logged that as well.

By 0730, when Morrison arrived at the observation post with a map and a pair of binoculars, Samuel had sketched a mental grid of likely German positions.

“Private Washington,” Morrison told him, “you have full authority to engage any targets of opportunity. The regiment wants these snipers neutralized.”

“Yes, sir,” Samuel answered. “They’re using a pattern. They’re rotating through fixed positions. That tells us where they’ll be next.”

When the third shot of the morning came from the original northeastern bunker at 0745, Samuel eased the Springfield against his shoulder and settled in behind the scope.

He exhaled slowly. He did not aim directly at the man. He aimed at the concrete barrier next to him.

The shot cracked across the valley. Concrete chips exploded eighteen inches from the German’s head.

It was, intentionally, a miss.

To anyone watching without context, it looked like a near hit. To Samuel, it was a calibration shot: a way to confirm his range estimate, check the wind, and send a message.

He’d been taught that the first shot should do more than just reach for a kill. It should gather information—and make the other side aware they were being watched.

A Duel Becomes a Lesson

The German response was swift. Several positions fired back in quick succession, trying to suppress the unseen American sniper. Bullets cracked into the walls and earth around Samuel’s post, but his concealment among broken farm buildings held.

Morrison, watching through his binoculars, assumed Samuel had simply missed and shouted advice about wind adjustment.

Samuel shook his head slightly.

“Sir, that round went exactly where I meant it to.”

The next shot came at a more distant eastern position Samuel had tracked earlier. He adjusted for range—around 500 meters—and wind. The bullet struck a support post, sending splinters spraying and forcing the sniper to duck back and move.

Within minutes, Captain Müller was on his field phone, telling his sniper teams they were facing a trained opponent, not random suppressive fire. He ordered relocation and coordination.

What followed for the next half hour was a test of will and perception.

With each engagement, Samuel moved from probing shots to direct ones. He put a bullet into a German’s shoulder at 450 meters. He cratered concrete edges, sending shards into firing slits. He clipped a moving soldier’s leg as the man sprinted between bunkers, forcing a risky rescue under observation.

Morrison watched his men on the valley floor begin to walk with a little less hesitation. Patrols that in previous days had hugged cover nervously now moved knowing someone was actively countering the threat.

The German marksmen felt something else: their sense of dominance dissolve. For weeks, they had been the unseen danger. Now, someone they could not spot was systematically dismantling their advantage.

Each American shot landed close enough to be instructional and unnerving.

The Pattern Breaker

Captain Müller, a veteran of North Africa and the Eastern Front, was not reckless. But he understood that letting an enemy specialist operate freely could be disastrous.

Shortly before 0900, he decided to see the situation himself from a forward observation point. He moved cautiously to a location he believed was shielded by angle and distance.

Samuel saw him through the scope.

He did not know Müller’s name. He did not need to. The way other soldiers deferred to the man, the way he moved, the equipment he carried—these were clear signs of someone in charge.

The range was about 540 meters—a difficult shot under training conditions, let alone from a concealed position under intermittent return fire with a “bad” scope.

The Springfield barked once more.

In the German lines, Müller staggered as a bullet tore into his shoulder. He went down. Medics scrambled. Orders stopped. For a moment, the entire sector seemed to exhale.

Then, slowly, the forward positions emptied. Snipers who had held their ground against patrols and tank advances began to pull back.

Within the hour, American units who had been pinned for two weeks advanced more than three miles.

What It Meant for the Americans

From a purely tactical standpoint, the outcome was clear: one American marksman, using a rifle and scope others had discarded as defective, had neutralized a network of German sharpshooters and disabled their local commander.

For the men on the ground, the difference was immediate. Patrols could move. Messages could be carried. Forward observers could do their work without feeling like they had a crosshair on them.

For Lieutenant Colonel Morrison—and, soon, for his superiors—the engagement raised deeper questions.

How many other “faulty” pieces of equipment were actually just misunderstood?

How many other soldiers, especially those from segregated units, were being underused because of assumptions rather than assessments?

Ordnance specialists later examined Samuel’s scope and found that its internal mechanisms were, in some respects, more sensitive than newer, sturdier models. It required fine adjustments and careful handling. In rushed hands, it seemed unreliable. In patient hands, it was extremely precise.

In other words, the scope had never been “bad.” It had simply needed someone willing to learn its language.

The same could be said of Samuel himself.

Quiet Pressure for Change

No single action overturns a system. The Army of 1944 did not suddenly integrate because one Black sniper proved his skill. But the report of what happened near Metz went up the chain of command, and somewhere in those stacks of papers, it became part of a growing weight of evidence.

Evidence that talent was being left on the table.

Evidence that equipment judged “inferior” could perform if given to people who understood it.

Evidence that ability did not sort itself neatly along the color lines drawn by tradition.

Morrison’s own reputation benefited from his decision to back Samuel’s deployment. Other officers, reading his after-action reports, took note—not just of the results, but of the thinking behind them.

In the years after the war, when debates about integrating the armed forces intensified, stories like Samuel’s—quietly cited in internal studies and training documents—added substance to arguments that the military could not afford to ignore competence anywhere it appeared.

Back Home, Back to the Delta

When the war ended and Samuel returned to Mississippi, there were no medals pinned on him in front of ticker-tape crowds. The country he came back to was still deeply segregated. The signs on café doors and bus seats had not changed because of what he did with a Springfield rifle in France.

He went back to what he knew: tools, wood, metal, the balance of a rifle in his hands.

He became a gunsmith and a hunting guide, known in his region for uncanny accuracy and endless patience. Clients respected him for his results, even if few knew the full story of where he had honed his skills under the harshest possible conditions.

On certain days, he took down a carefully oiled case and opened it to reveal an old, battered scope.

To most eyes, it was unremarkable. The brass was scuffed. The markings were worn. But to Samuel, it was a reminder—a symbol of what could be done when someone refused to accept that “not good enough” was the final judgment.

Out in the Delta, under the same kinds of skies where his grandfather had once taught him to wait for the right shot, he adjusted the turrets as naturally as breathing, compensating automatically for quirks that once confounded others.

Then he settled in, watched the wind, and waited.

The fog in the Moselle Valley lifted long ago. The concrete bunkers are cracked and overgrown. The reports written by Morrison and his peers gather dust in archives. But the lesson still matters:

Tools are only as limited as the imagination and patience of the person using them.

Assumptions—about equipment, about people, about who might be capable of excellence—can be as dangerous as any enemy.

And sometimes, on a quiet morning in a far-off valley, one person who refuses to accept those assumptions can shift more than just a battle line.

News

This Farm Boy Fixed a Jammed Machine-Gun — And Changed the Battle

On a foggy French hillside in the early hours of September 13, 1944, a 19-year-old farm boy from Iowa found…

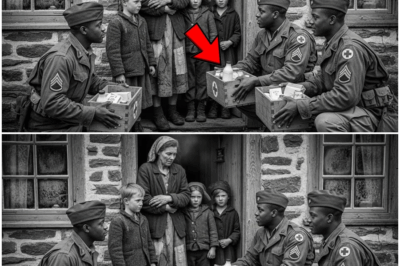

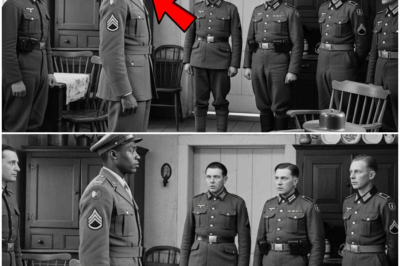

THE DAY THEIR WORLD CRUMBLED: German Women POWs See Black American Soldiers for the First Time—And the Shockwave Changes Everything.

On a muddy patch of ground outside Remagen in March 1945, two worlds that had been taught to despise one…

“I Thought They Were Devils,” German Woman Said After Black Soldiers Saved Her Starving Family

The chimneys in Oberkers had been cold for weeks. Snow lay heavy on the sagging roofs of the small German…

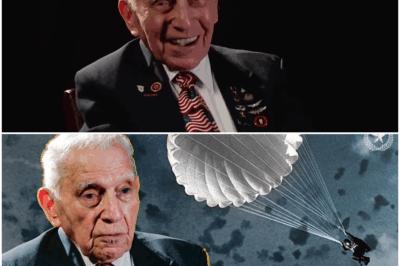

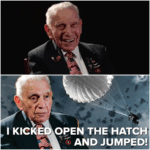

He Bailed out of Crashing B-17 over Germany and Survived being a POW

The young man from Brooklyn wanted to look older. In the fall of 1941, Jerry Wolf was a wiry teenager…

MOCKED. CAPTURED. STUNNED: Germans Taunted a Black American GI — Then His Unthinkable Act Silenced the Entire Nazi Camp.

Caught in the Winter Storm On the morning of December 15th, 1944, the frozen fields of the Ardennes lay under…

THE MOCKERY ENDS: Germans Taunt Trapped Americans in Bastogne—Then Patton’s One-Line Fury Changes Everything.

Lieutenant General George S. Patton Jr. walked into the Ardennes crisis with a reputation that was already larger than life….

End of content

No more pages to load