In the suffocating heat of central Vietnam, there were a thousand ways to die. Booby traps waited in the earth. Mortars fell without warning. Disease could sap a man’s strength faster than any bullet.

But for the Marines on Hill 55, it wasn’t the unseen mines or random artillery that kept them awake at night.

It was a name.

They called her Apache.

To some she was a flesh-and-blood enemy sniper—small, fast, patient, with a gift for marksmanship and a reputation for cruel treatment of prisoners. To others she was a rumor grown into a kind of ghost story, a way to explain the sudden, surgical deaths that stalked their perimeter.

Whatever the truth, Apache became more than a person. She became a symbol of everything that was strange and frightening about the war in Vietnam. And for Gunnery Sergeant Carlos Hathcock, one of the most skilled American marksmen of the conflict, she also became a mission.

This is the story of that mission—and why it still echoes, half fact and half legend, decades after the last helicopter lifted away.

Hill 55: A High Place in a Low War

Hill 55 rose out of the countryside like a clenched fist—just high enough to dominate the surrounding rice paddies and scrub-covered ridges. Eight miles southwest of Da Nang, it served as a Marine base, artillery position and observation post. In theory, it was a place of relative safety.

In reality, it was a target.

The ground around Hill 55 was a maze of gullies, bamboo, hamlets, hedgerows and tree lines. The Viet Cong knew every path and stream. They could move close under cover of darkness, watch the Marines from just beyond the perimeter, then vanish before dawn.

At first, the danger felt familiar: sporadic rifle fire, occasional probes, and the ever-present threat of mines. But in late 1966, a different pattern emerged.

Marines on watch were being killed by single, precise shots. No wild bursts, no messy firefights—just one round, placed exactly where it would do the most harm. The distances involved, often hundreds of yards, meant this wasn’t ordinary guerrilla fire. Someone with training was out there.

At the same time, patrols began finding the bodies of captured allied soldiers who had been treated with a particular kind of malice. Details spread in whispers—stripped followers of the code of “we look after our wounded, they look after theirs”—and the anxiety level on the hill spiked.

Out of those facts and rumors, one figure emerged in the Marines’ conversations: a female sniper, of mixed Vietnamese and French background, operating with a small unit in the area around Duc Pho and Hill 55. She was said to be exceptionally skilled, feared even by some of her own side, and notorious for what she did to those who fell into her hands alive.

They called her “Apache”, a nickname that said more about American soldiers’ frame of reference than about Vietnam itself, but it stuck. She became the story you heard on watch at 2 a.m., the shape you imagined in the treeline, the explanation for the next man who went down with a single neat wound.

It would have stayed a campfire legend—except that the body count was real.

A Hunter Arrives

If there was anyone the Marines wanted on their side in a duel like that, it was Carlos Hathcock.

He was not a large man, nor did he look particularly fearsome. Raised in rural Arkansas, Hathcock had grown up hunting rabbits and deer to put food on the table. He learned early that in the woods patience mattered more than bravado. You waited. You watched. You didn’t fire until you were sure.

The Marine Corps gave him a rifle and a discipline to match that temperament. By the time he arrived in Vietnam, he had already built a reputation as one of the best long-range shooters in the service. He preferred a Winchester Model 70 bolt-action rifle, chambered in .30-06, topped with a simple scope. No gimmicks. Just a man, a rifle, and an almost eerie ability to sit motionless for hours.

When Captain Edward “Jim” Land, the Marine sniper program’s architect, briefed Hathcock on the situation at Hill 55, he didn’t dwell on the more lurid rumors. He stuck to what could be verified: a string of dead Marines with single, carefully placed wounds; reports from South Vietnamese allies about a skilled female fighter operating in the area; and the evidence from recovered bodies that she was using fear as deliberately as she used bullets.

Command wanted her stopped—not out of personal vendetta, but because her continuing presence was eating away at the unit’s morale. Men hesitated to move beyond the wire. Every rustle in the brush felt like the beginning of a carefully prepared ambush. It wasn’t sustainable.

Land and Hathcock were given a simple but daunting assignment: find her, and end it.

Pattern of a Predator

Hathcock didn’t march out into the jungle looking for a showdown. He started the way a good hunter always does—by studying the ground.

Over maps and aerial photos, he and Land looked for logic in the scattered reports. Where had the ambushes happened? Where had patrols been hit? Where had allied bodies been found? When you plotted those points, certain things became clear.

The enemy sniper was using ridgelines with good observation over Marine patrol routes. She favored areas with access to water and quick escape paths. Campsites identified by South Vietnamese scouts were always temporary, relocated every couple of days. This was someone who understood that survival depended on never being predictable.

They marked probable movement corridors—small draws, dry creek beds, folds in the land that offered concealment. Then they did what snipers do best: they disappeared into that same landscape themselves.

Before dawn each day, Hathcock and Land would slip past the American perimeter, moving light—rifles, ammunition, canteens, a little food. They’d settle into carefully chosen hides on high ground or overlooking suspected trails and wait.

Nineteen hours in the heat, mosquitoes whining, muscles cramping, eyes burning from staring through glass. They watched patrols of Viet Cong fighters, sometimes at ranges so far that the figures seemed to float in heat haze. More than once, Hathcock lined up a shot and then chose not to fire. Taking a lesser target risked giving away their presence before the primary quarry appeared.

Meanwhile, the psychological war continued on Hill 55.

One night, the screams of a captured Marine carried clearly across the valley. Men gripped their rifles so tightly their knuckles whitened. Some begged to go out after him. Hathcock and Land said no. A large, angry reaction force charging into the jungle in the dark was exactly the kind of thing their opponent would be expecting—and planning for.

It was a hard order to give, and harder to accept. But patience saved lives in this war as surely as any act of courage.

At first light, a badly wounded Marine staggered out of the treeline and collapsed. The extent and nature of his injuries confirmed that the stories about Apache’s cruelty were not just campfire fuel. For Hathcock, who had seen more than his share of violence, it crossed a line.

The hunt became personal.

Two Hunters in the Green

The next morning, after briefing Lieutenant Colonel Davidson, the battalion commander, Hathcock and Land proposed an approach that went against every instinct for a conventional response.

No large patrol. No noisy sweep.

Just the two of them.

“Two men?” Davidson asked, incredulous. “Against her whole squad?”

“Two hunters,” Hathcock answered. “Not a herd.”

In dense jungle, a big unit is its own worst enemy. Dozens of boots break twigs, flatten grass, announce their presence with every step. A sniper who has lived off the land for years can hear them long before they ever get close.

Two men moving slowly and carefully, on the other hand, can become nearly invisible.

They left within the hour, following the faint sign left by the group that had dragged the captured Marine away: a smear of blood here, a bent stem there, the tiniest disturbances in the undergrowth. At times the trail vanished outright where rain or rocky soil had erased any obvious trace. That was when experience came into play.

Hathcock read the jungle like a familiar book. Here a notch in the bark where a rifle barrel had brushed a tree. There a footprint half-hidden in leaves. Above, in the canopy, the way birds had gone suddenly silent at some recent disturbance.

By midday they had covered several kilometers. Occasionally they found crude rest sites: cigarette butts, water-boiled over small fires, impressions in the grass where people had lain down. The Viet Cong patrols were diligent. But they were not perfect. Nobody is, all the time.

Toward afternoon, the ground began to rise. The trail angled up toward a ridge that offered a commanding view over the valley—exactly the kind of vantage point an experienced sniper would choose.

Hathcock and Land eased into position on a neighboring rise, belly-crawling the last few feet, using every dip and rock to stay low. Through the lens of his Unertl scope, Hathcock scanned the ridgeline.

Nothing.

For long minutes, only leaves and rocks filled the crosshairs. Then, movement. Five figures emerged along the crest, pausing to survey the terrain. All were armed. One carried a rifle with a scope.

Even at that distance, the woman’s build and posture matched the descriptions they’d been given.

They watched as the small group picked its way forward, then halted near a cluster of rocks. The woman spoke to the others, gesturing toward the valley below, no doubt planning their next move. Then, as if on cue, she stepped away toward a patch of low bushes.

Land, watching through binoculars, realized what she was doing and murmured a quick update: she was momentarily alone and distracted.

It was the opening they had been waiting for.

A Hard Shot, A Quiet Ending

Sniping is not like in the movies. At 700 meters, even with a good rifle and scope, there is nothing easy about a shot.

Wind pushes a bullet sideways as it travels. Gravity drags it downward. Heat rising off the ground can distort the image. The shooter’s own heartbeat can nudge the barrel a hair at the critical instant.

Land ran the math out of habit: distance, approximate wind speed, angle. Hathcock made the necessary corrections on his scope, then settled into the firing position he had practiced thousands of times before.

He let his breathing slow. In that moment there was no “Apache,” no Hill 55, no legend—just a target and a job.

He pressed the trigger.

Through the scope, he saw the impact. The woman jerked, staggered, and fell. For a second she tried to move. A second shot ended the effort. Her companions dropped to the ground, scanning frantically, firing blindly into the trees, not knowing where the threat had come from.

Almost immediately, Land got on the radio to call in artillery on the ridgeline. Within minutes, shells walked up and down the crest, shaking the earth, shredding undergrowth, and scattering the surviving fighters. The barrage also served another purpose: it erased the exact details of what had just happened under a wall of noise and dust.

When the guns fell silent and the jungle’s normal sounds began to creep back in, Hathcock and Land slipped away the same way they had come—quiet, low, leaving as little sign as possible.

Back on Hill 55, when they reported the outcome, nobody asked for photographs or fingerprints. In that kind of war, absolute certainty was rare. What mattered was practical effect.

The sniper believed to be Apache was gone.

Fear, Symbols, and the Truth We Can’t Untangle

Did Gunnery Sergeant Carlos Hathcock really kill a specific woman known to the Marines as Apache?

By his own account, and by the accounts of men who served with him, yes. They believed it then, and many of them believe it now.

Did Apache truly carry out all the acts ascribed to her in stories told on sandbag walls and in memoirs? That is harder to say. Much of the detail about her life and actions comes not from captured documents, but from prisoner interrogations, local rumor, and the human tendency to weave separate events into a single narrative.

In other words: some of what is told about her may be accurate, some may be exaggeration, and some may be myth laid over a kernel of truth.

What is not in doubt is this:

The Marines around Hill 55 were being harassed and killed by a persistent enemy sniper.

The way those attacks were carried out—long-range, single shots, repeated over days and weeks—had a powerful psychological effect.

Hathcock and Land conducted a deliberate hunt for that threat, using patience, fieldcraft and marksmanship to remove it.

When they returned to base believing they had succeeded, morale improved noticeably.

In that sense, “Apache” became less important as an individual and more important as a symbol. She embodied the fear of an invisible, intelligent enemy who seemed always a step ahead. Her defeat, whether they knew every detail or not, gave exhausted young men something they badly needed: proof that they were not helpless.

Hathcock himself, reflecting on his time in Vietnam years later, rarely spoke in terms of heroes and villains. He talked about the work, about the toll it took, about how each life he ended stayed with him. To him, the mission on Hill 55 was one more job that had to be done to keep his fellow Marines alive.

What the Story Really Tells Us

It’s easy to see this as a simple tale: a feared enemy, a brave hunter, a perfect shot. But the more you look at it, the more complex it becomes.

You see:

How fear spreads in a small unit, and how quickly rumor can turn one enemy fighter into a larger-than-life figure.

How morale and psychology matter as much as ammunition in long, grinding wars.

How much warfare at the small-unit level depends on individuals with particular skills—on the patience of one sniper, the discipline of one scout, the resolve of one young Marine who doesn’t panic under pressure.

How stories themselves can become weapons, for good or ill.

For the Marines on Hill 55, Apache was very real, whether she matched every detail of later retellings or not. For the Viet Cong, she may have been simply another capable comrade. For historians, she sits in a grey zone where verifiable fact and oral history blur together.

What remains clear is the impact of the hunt.

A base that had been living under a shadow for weeks suddenly felt that shadow lift. Patrols went out with a little more confidence. Men on watch still scanned the tree line—but the name they had been whispering in the dark stopped appearing as often.

In that sense, the story of Apache is less about celebrating violence and more about understanding the strange, human side of war: how one person’s reputation can sway the emotions of hundreds, and how deeply the acts of a few individuals, on both sides, can echo through the minds of those who survive.

Whether you see Apache as a flesh-and-blood sniper, a composite of several fighters, or a wartime legend, her story—like so many from Vietnam—reminds us that behind every myth are real people, caught up in forces far bigger than themselves.

And somewhere on a misty ridge above Hill 55, two hunters once lay in the grass, watching, waiting, and bringing one chapter of that story to an end.

News

THE ‘REJECTED’ HERO: The Army Tried to Eject Him 8 Times—But This Underdog Stopped 700 Germans in an Unbelievable WWII Stand.

On paper, Jake McNiece was the kind of soldier any strict army would throw out. He questioned orders. He fought…

HE 96-HOUR HELL: Germany’s Elite Panzer Division Vanished—The Untold Nightmare That Shattered a WWII Juggernaut.

On the morning of July 25, 1944, Generalleutnant Fritz Bayerlein stood outside a battered Norman farmhouse and read the sky…

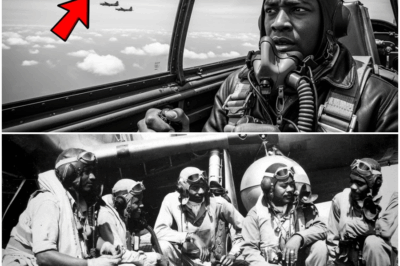

THE TUSKEGEE GAMBLE: The Moment One Pilot Risked Everything With a ‘Fuel Miracle’ to Save 12 Bombers From Certain Death.

Thirty thousand feet above the Italian countryside, Captain Charles Edward Thompson watched the fuel needle twitch and understood, with a…

THE ‘STUPID’ WEAPON THAT WON: They Mocked His Slingshot as a Joke—But It Delivered the Stunning Blow That Silenced a German Machine-Gun Nest.

In the quiet chaos of Normandy’s hedgerow country, where every field was a trap and every hedge could hide a…

THE HIDDEN MESSAGE IN A MARINE’S PORTRAIT: It Looked Like a Standard Family Photo, But One Tiny Detail in Their Hands Hides a Staggering Secret.

In a small studio at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, a photographer captured what looked, at first glance, like a routine…

This Farm Boy Fixed a Jammed Machine-Gun — And Changed the Battle

On a foggy French hillside in the early hours of September 13, 1944, a 19-year-old farm boy from Iowa found…

End of content

No more pages to load