In the spring of 1945, with the Second World War all but decided, a German submarine captain found himself in the kind of position most commanders only ever experience in training scenarios and daydreams.

He was invisible.

His enemy was exposed.

His weapon was decades ahead of its time.

And he did not fire.

That moment — just a few quiet seconds on May 4th, 1945 — tells you almost everything you need to know about the most advanced submarine of the war, the Type XXI “Elektroboot”, and why it arrived too late to matter.

A Perfect Shot That Never Happened

May 4th, 1945 – North Atlantic, 180 km off the Scottish coast

Kapitänleutnant Adalbert Schnee, already a highly decorated U-boat commander, peered through the periscope of U-2511. Ahead of him, at just 500 yards, steamed HMS Norfolk, a British heavy cruiser of 10,000 tons, with four destroyers fanned out in an escort screen.

For any submarine commander, this was the dream scenario:

The target was large, valuable, and vulnerable

The escorting destroyers had no idea he was there

He was at point-blank range

His tubes were already loaded: six modern electric torpedoes, silent-running and wakeless

Schnee had sunk 21 ships over four years of war. He knew the drill by heart: line up the shot, give the order, listen to six torpedoes leave the tubes at three-second intervals, then brace for the distant thumps as they struck home.

But this day was different.

Earlier that morning, U-2511’s radio operator had handed him a signal from higher command. It was short and cryptic:

“Cease all offensive operations. Effective immediately. Await further orders.”

No explanation. No context. No mention of surrender. Snow still fell elsewhere, and gunfire still echoed on other fronts. As far as the crew knew, the war was still on.

Now, with Norfolk framed perfectly in his periscope, Schnee’s hand settled on the firing lever — and stopped.

By every tactical measure, this was the moment the new German submarine design had been built for. The escort screen had never detected him. The advanced hull, electric drive, and sound-absorbing coating had done their job. U-2511 had approached an alerted, combat-ready Allied task group to pistol-shot range without being noticed.

If he fired, he would almost certainly sink a British cruiser and probably escape. He would prove, in combat, that this new submarine was a game-changer.

He took his hand off the lever.

“Secure from battle stations,” he said quietly. “Break contact. Come to new course. Depth one hundred meters.”

U-2511 turned silently away. HMS Norfolk and her escorts plowed on, the crews unaware that they had been 30 seconds from disaster.

The war would officially end just a few days later.

Schnee’s decision — and the technology that enabled that position in the first place — became the backbone of post-war analysis in British, American, and Soviet naval circles. Because the submarine he commanded, the Type XXI, was not just another U-boat.

It was a glimpse of the future, delivered when the war was already lost.

Why the Old U-Boats Were Dying

To understand why the Type XXI mattered — and why it ultimately didn’t — you have to go back to January 1943 and a cold, unforgiving statistic that stared German naval command in the face.

For months, U-boats had been sinking Allied shipping at frightening rates. But the Allies had adapted. Radar, sonar, air patrols, escort carriers, and better tactics turned the Atlantic into a far more dangerous place for submarines.

In late 1942 and early 1943, the losses flipped:

October 1942: 38 U-boats lost

November 1942: 41 U-boats lost

December 1942: 43 U-boats lost

The standard Type VII submarine — the workhorse of the German fleet — had reached the end of its technological rope. Its weaknesses had become fatal:

Maximum submerged speed: about 8 knots

Maximum depth: around 220 meters

Slow underwater endurance

Vulnerable to radar when on the surface

Noisy and relatively easy to track once detected

Once a convoy escort picked up a Type VII on sonar or radar, the odds of escape were poor. Submerged, it was slower than the ships hunting it. It could dive, but not so deep that improved depth charges couldn’t reach it. It had become what no military system can afford to be: predictable.

Admiral Karl Dönitz, who commanded the submarine arm, knew that incremental upgrades wouldn’t solve this. The Allies were climbing the same ladder but faster, with more factories and more planes.

He needed something qualitatively different.

Designing a Submarine for the World After 1943

In early 1943, German engineers were given a bold set of requirements:

Underwater speed: at least 15 knots (fast enough to outrun escort destroyers underwater)

Depth: at least 280 meters (deeper than most Allied depth-charge settings at the time)

Firepower: at least 20 torpedoes, with fast reloading systems

Stealth: minimal radar and sonar signature

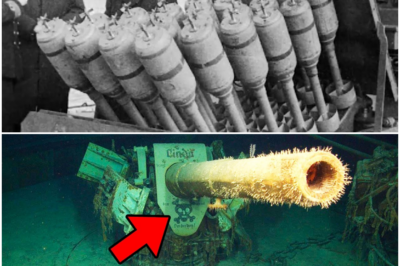

The result, on paper, looked radical:

A smooth, teardrop-shaped hull optimized for underwater travel, not surface cruising

A streamlined, low-profile “sail” (the updated conning tower), reducing drag and radar return

Enormous battery capacity, roughly triple that of earlier boats

Powerful electric motors capable of sustained underwater speeds around 17 knots in short bursts

A snorkel system to run diesels while submerged just below the surface

Hydraulic torpedo reloads that could refill all six bow tubes in about 10–12 minutes

This new submarine was called the Type XXI “Elektroboot.” It was, in many ways, the first modern submarine; not just a surface ship that could submerge, but a fully underwater vessel designed to live and fight beneath the waves.

In trials, the Type XXI turned numbers into reality:

It could stay submerged far longer than earlier boats

It could move faster underwater than most surface ships could hunt

It was quieter and harder to find

It could, in theory, ambush a convoy from below and slip away before destroyers closed in

It is no exaggeration to say that every major submarine built after the war — British, American, Soviet — borrowed heavily from this blueprint.

But great engineering is only half the story.

The other half is timing.

Built for 1943, Delivered in 1945

The design work began in earnest in early 1943. If everything had gone perfectly — if there had been no bombing, no shortages, no disruptions — the first operational Type XXI might have gone to sea in late 1943, with full squadrons following throughout 1944.

That did not happen.

By 1943, the Allies’ strategic bombing campaign was hitting shipyards, factories, rail lines, and fuel depots across Germany. The submarine program was no exception:

Shipyards built hull sections, but rail lines to assembly yards were bombed

Factories made engines, but parts shortages and power cuts slowed output

Skilled workers were increasingly drafted into the army, leaving less experienced teams to handle complex tasks

Completed submarines often sat without trained crews, or without fuel, or without working torpedo stocks

On paper, 118 Type XXI submarines were completed by war’s end.

In reality:

Only a handful ever sailed on true patrols

Most never left port

The majority never fired a torpedo in anger

U-2511, Schnee’s boat, was among the very first to become operational — in late April 1945.

By that point:

Allied forces were already on German soil

Most of the Atlantic supply routes were secure

The submarine war that had once threatened Britain’s survival was effectively over

The Type XXI had finally arrived… at the closing ceremony.

The Eight-Day Submarine

From commissioning to surrender, U-2511 had eight days of war left.

In those days, the submarine did exactly what it had been built to do:

It moved quietly

It remained undetected

It approached a heavily escorted cruiser to impossibly close range

Schnee proved, in that encounter with HMS Norfolk, that the design worked not just in tests, but in the unforgiving chaos of the ocean.

A British naval officer who inspected U-2511 after the surrender reportedly summed it up bluntly:

“If you’d had a few hundred of these in 1943, we’d have had a very serious problem.”

British engineers took the boat apart piece by piece. So did American and Soviet teams on other captured examples. Within a few years:

Streamlined hulls appeared in Western and Eastern submarine fleets

Snorkel systems became standard

High-capacity battery banks were the norm

Fast reload torpedo rooms were no longer exotic

Technologically, the Type XXI “won.”

Strategically, it came second to the calendar.

The “What If” That Matters — and the One That Doesn’t

It’s tempting to play the big “what if” game.

What if Germany had deployed 300 Type XXI submarines in 1943?

On a purely tactical level, the consequences would have been severe:

Convoys would have faced faster, quieter submarines able to strike from unexpected angles

Escort ships would have struggled to detect and pin them down

Shipping losses would likely have spiked again, possibly matching the worst months of 1942

That, in turn, might have delayed:

The build-up of men and material in Britain for the landings in France

The timing of D-Day

The speed at which Allied armies advanced into Europe

But there is another “what if” that often gets overlooked.

What if Germany had somehow solved not just the engineering problem, but the industrial problem too?

Because that’s the real gap.

The Allies:

Built ships faster than submarines could sink them

Replaced escorts faster than the U-boats could destroy them

Expanded air cover faster than submarines could adapt to it

The Type XXI was, in many respects, a superb answer to a very specific tactical question: How do we build a submarine that can survive — and win — in a 1943–1944 Atlantic full of radar-equipped destroyers and aircraft?

But answers like that don’t win wars alone.

Wars at sea are ultimately decided by:

Shipyards

Logistics chains

Fuel reserves

Training programs

The ability to out-produce the other side over years, not months

And in that sphere, no late-war German submarine, however advanced, could close the gap.

A Captain, a Lever, and a Quiet Admission

When Schnee took his hand off the firing lever on May 4th, 1945, he made a choice that was part obedience, part intuition, and part quiet recognition.

He obeyed the ceasefire order.

He avoided turning his last patrol into an incident that might outlive the war.

And he understood — as many officers did by then — that no single action, no matter how daring or technically impressive, could change the outcome.

The Type XXI had done its part.

The engineers had done theirs.

The captain had done his.

But the war was no longer decided in periscope crosshairs.

It had been decided in factories, on shipways, along supply lines, and in a thousand industrial decisions made years before.

Schnee later reflected that Germany had finally built the submarine that could have made the sea war truly dangerous again — and that it arrived about two years too late.

His boat never fired a wartime torpedo.

Yet what U-2511 demonstrated in those few days at sea reshaped submarine design for generations. Every modern attack submarine carries some of its DNA.

The lesson is as relevant now as it was then:

Technology matters.

Tactics matter.

Skill at the sharp end absolutely matters.

But time and industry matter more.

The Type XXI was proof that you can, in fact, build a weapon that’s years ahead of anyone else’s — and still lose, simply because you built it after the moment when it could make a difference.

In a quiet control room, in a submarine that the enemy never even knew was there, a captain let a perfect shot go.

Not because the weapon didn’t work.

Because the war already had.

News

The Forbidden Weapon: How One Private Defied Orders, Used the ‘Wrong’ Grenades, and Became a Legend in the Pacific

In May 1944, on a coral island few Americans had ever heard of, a farm kid from Iowa quietly rewrote…

The Silent Steel Trap: This Underdog Weapon Decimated the U-Boat Fleet and Won the Battle of the Atlantic

In the early, uncertain years of the Second World War, the North Atlantic stopped being an ocean and became a…

The ‘Animal Hunter’s’ Day Job: Inside the Terrifying 152mm World of the ISU-152 Crew

The diesel cough from the engine swallowed the world, and for a moment the only thing that existed was metal,…

SENATE FLOOR SHATTERED: AOC’s ‘TIME IS OVER’ Declaration vs. Kennedy’s ‘Darlin’ Comeback’

The exchange was brief, the line was sharp, and within hours it had been replayed, reframed, and argued over in…

The Junkyard Miracle: How One Desperate WWII Pilot’s ‘DIY’ Bomb Flipped a Deadly Night Battle—The Improvised Device That Defied Science and Saved His Squadron, Leaving Enemy Aces Stunned. Uncover the Improbable Tale of the ‘Backyard’ Weapon That Re-Wrote Aviation History!

On a freezing December night in 1944, in a shallow shell crater outside a Belgian town called Büllingen, one American…

The Uncanny Prophecy: How a Star Luftwaffe Ace, Ten Months Before D-Day’s Fury, Saw the Third Reich’s Doom Written in the Skies—His Ominous Pre-War Warning That Chilled the High Command and Was Branded Treasonous, Now Revealed. Discover the Secret Memo Detailing Germany’s Inevitable Fall! 🤫

On a gray August morning in 1943, a decorated German night-fighter ace walked out onto the tarmac at Rechlin, the…

End of content

No more pages to load