on a freezing April morning in 1940, in rough seas off the coast of Norway, a small British destroyer met a German heavy cruiser more than ten times its size. What followed was one of the most improbable and audacious actions in naval history — an attack so unexpected that even the enemy commander later wrote to London recommending the British captain for his country’s highest award for gallantry.

This is the story of HMS Glowworm, Lieutenant Commander Gerard Broadmead Roope, and the decision to turn a doomed destroyer into a weapon.

A Lone Destroyer in the Wrong Place at the Worst Time

April 8, 1940 – Norwegian Sea

HMS Glowworm was not meant to fight alone. She was part of a larger British force covering operations off Norway, but heavy weather and a long, wearying search for a man lost overboard had separated her from the battlecruiser HMS Renown and the rest of the screen.

For nearly a day, Roope had held his destroyer in dangerous seas searching for the missing sailor. The weather was appalling: 30-foot swells, spray blasting across the decks, men thrown from their feet as the ship rolled. Glowworm’s gyrocompass failed in the violence of the storm, forcing the ship to navigate by magnetic compass alone.

By the time the hunt was called off, the destroyer was tired, behind schedule, and effectively alone.

At 08:00, lookouts spotted smoke. Two German destroyers appeared out of the murk — Z11 Bernd von Arnim and Z18 Hans Lüdemann — part of the German invasion force heading for Trondheim under Operation Weserübung, the occupation of Norway.

The war in the north had just gone from uncertain to very real.

Outnumbered, Outgunned — and Advancing Anyway

Roope had three choices: turn away, shadow the enemy, or engage.

He chose to open fire.

Glowworm’s 4.7-inch guns flashed in the gloom, and the German destroyers answered back. Very quickly it became clear that the German ships were not trying to stand and fight but to draw the British destroyer somewhere else — toward something larger.

Roope likely guessed this. But he also knew something else: if major German units were at sea, the British Admiralty had to be warned.

He signaled a contact report and kept chasing.

The weather was still punishing. More men were swept overboard. Visibility dropped, then cleared, then dropped again. Glowworm’s crew fought their own ship as much as the enemy — straining to keep guns loaded on a wildly rolling deck, working the engines hard enough to keep the Germans in sight without breaking machinery already hammered by the storm.

At 09:50, the fog lifted for less than a minute.

It was enough.

Emerging out of the gray was a vast shape: the German heavy cruiser Admiral Hipper.

“An Impossible Fight” — the Odds Against Glowworm

The contrast between the two ships was almost absurd.

Admiral Hipper:

Displacement: ~14,000 tons

Main armament: Eight 8-inch guns

Thick armor designed to resist large-caliber shells

HMS Glowworm:

Displacement: ~1,350 tons

Main armament: Four 4.7-inch guns

Lightly armored hull, essentially a fast, thin-skinned gun platform

On paper, this was not a fight but an execution.

At around 10:00, Hipper opened fire at long range. Salvo after salvo roared out from the cruiser’s heavy guns. Within minutes, Glowworm was hit:

The bridge and director control were damaged

The forward guns were knocked out

The radio room was destroyed

Electrical failures added to the chaos

Glowworm’s siren jammed and began to sound continuously — a haunting, involuntary wail over the noise of battle.

Roope responded with classic destroyer tactics: he laid smoke and turned into it, trying to break the cruiser’s fire control solution and buy precious seconds.

Behind that smoke screen, he made his next move.

Torpedoes at Point-Blank Range

Glowworm carried ten torpedo tubes in two quintuple mounts. She had been a test ship for this new arrangement and was one of the few British destroyers with that configuration at the time.

Roope turned back through his own smoke and emerged at short range.

The cruiser filled the horizon.

At around 400 yards — a distance where even small details on the German decks were visible — Glowworm fired a full spread of ten torpedoes.

For a brief moment, this small, battered destroyer held the kind of offensive power that could cripple a major warship. Ten tracks raced through the sea toward the heavy cruiser.

The crew watched, willing them to hit.

One torpedo track reportedly passed dangerously close to Hipper’s bow. Thanks to quick maneuvering by her captain, the cruiser managed to comb the spread. All ten missed.

Glowworm’s main offensive weapon was gone.

Her forward guns were out of action, the ship was badly damaged, and the enemy cruiser still loomed ahead with all its main guns and most of its secondary battery intact.

In that moment, the battle could have ended in a predictable way: Roope might have tried to disengage, laying smoke and running in hopes of rejoining British forces, or he might have chosen to surrender to save the lives of the remaining crew.

He did neither.

Turning a Ship into a Weapon

Instead, Roope gave an order that belonged to an earlier age of naval warfare.

He ordered hard right rudder and pointed his ship straight at the enemy.

Destroyers are nimble. Heavy cruisers are not. Although Hipper was still trying to turn to meet this unexpected threat, her sheer mass meant she could not pivot as rapidly as the smaller Glowworm.

The British destroyer accelerated — or what counted as acceleration for a ship already riddled with damage and flooding. One remaining gun kept firing, defiant to the last.

At approximately 10:13, Glowworm struck.

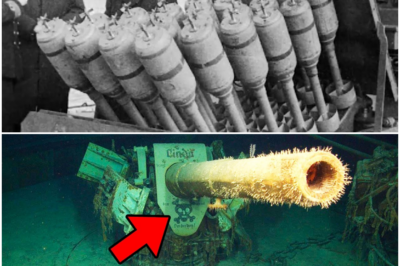

Her bow collided with Hipper’s armored belt. The forward section of the destroyer was crushed instantly, but momentum carried the rest of the hull along the cruiser’s starboard side. Glowworm scraped down Hipper’s flank, tearing off armor plating, smashing fittings, and inflicting deep structural damage.

The impact:

Tore away roughly 100 feet of armor plating

Damaged or destroyed one of Hipper’s torpedo mounts

Opened serious holes in the hull below the waterline

Caused flooding in forward compartments

Damaged the ship’s freshwater system — crucial for boiler operation

Glowworm paid for that impact with her life. Her bow was effectively gone. Fires raged aboard, flooding increased, and power declined. Still, the aft gun managed to fire a few more shells at the cruiser from point-blank range before being silenced.

Minutes later, the destroyer was fatally wounded.

“Abandon Ship”

At roughly 10:17, Roope gave the order to abandon ship.

The scene that followed was as brutal as anything in naval war:

Seas were still heavy, with large waves battering the damaged hull

Water temperatures in the Norwegian Sea were near freezing

There was no time to organize lifeboats properly

Many men had to jump straight into the sea with only life jackets

Glowworm rolled onto her side, her hull a twisted, burning mass. Some men tried to climb onto the upturned keel. Others jumped clear as explosions and flooding tore the ship apart.

At around 10:24, the boilers exploded. The destroyer broke apart and sank. Of the 149 men aboard Glowworm, only 31 survived the sinking.

Witnesses later said Roope was seen in the water helping his men, pushing life jackets toward others, urging them to get clear. When German sailors from Hipper later threw him a line and tried to pull him up, he lost his grip and slid back into the sea.

He was never seen again.

The Enemy Who Stopped and Helped

One of the most remarkable elements of this event is what happened aboard Admiral Hipper.

Hipper’s captain, Kapitän zur See (Captain) Helmuth Heye, did something that went against every operational instinct in wartime: he ordered his ship to stop and rescue survivors.

This was no small act. They were:

In hostile waters

Aware that British forces, including the battlecruiser Renown, were somewhere nearby

Commanding a ship that had just been damaged by a surprise attack

Stopping meant vulnerability. It also meant humanity.

Heye maneuvered his cruiser so that currents would push surviving British sailors toward the hull. He ordered ropes and cargo nets thrown over the side. His own crew, including embarked German soldiers bound for the invasion of Norway, worked to pull the oil-soaked, freezing men aboard.

Not all could hold on. Some survivors lost their grip, weakened by cold and exhaustion, and slipped back into the sea.

Thirty-one men from Glowworm were eventually saved.

Heye brought them aboard, had them fed and given dry clothing. He also spoke to them about their captain, telling them they had fought bravely and that their commanding officer had shown extraordinary courage.

Then, when he had the chance, he did something even more unusual.

He sat down and wrote a letter.

A Letter That Took Five Years to Arrive

In August 1940, months after the battle, Heye wrote a report addressed to the British authorities via the International Committee of the Red Cross. In it, he described the action and specifically recommended Lieutenant Commander Gerard Roope for the Victoria Cross, Britain’s highest decoration for bravery.

He stated that Roope had:

Engaged superior forces with determination

Continued fighting in heavy conditions despite multiple hits

Made a deliberate decision to ram his cruiser

Fought, in Heye’s judgment, with a level of courage deserving of the highest recognition

Getting a letter from a German warship commander to the British Admiralty during wartime was not a quick process. The channels involved diplomacy, Red Cross protocols, and censorship on both sides.

The letter went into the machinery of wartime bureaucracy.

It did not emerge again in Britain until late 1945.

By then:

The survivors had been prisoners of war for five years

Roope had been “missing, presumed killed” for just as long

The war in Europe was over

Glowworm had become just one of many ships listed as lost

When the letter finally landed on a desk in London and was matched with the testimonies of the surviving British crew, it changed everything.

Recognition at Last

The Admiralty reviewed:

Heye’s detailed account

Statements from Lieutenant Robert Ramsay and the other 30 survivors

Technical assessments of the damage Admiral Hipper had sustained

They concluded that Roope’s actions met — and arguably defined — the standard for the Victoria Cross: “most conspicuous bravery, or some daring or pre-eminent act of valour or self-sacrifice.”

On July 6, 1945, the London Gazette formally announced that Lieutenant Commander Gerard Broadmead Roope, Royal Navy, had been awarded the Victoria Cross, posthumously, for his actions on April 8, 1940.

The citation described how Glowworm:

Engaged two enemy destroyers in heavy seas

Continued the pursuit despite the danger

Encountered and fought a much larger cruiser

Fired torpedoes at close range

Finally rammed Admiral Hipper in a deliberate act of attack

Roope became:

The first person to earn a Victoria Cross in World War II (though not the first awarded, due to timing)

One of a tiny number of individuals whose VC recommendation came, in part, from an enemy officer

In February 1946, his widow, Faith Roope, received the medal from King George VI at Buckingham Palace.

More Than a Heroic Story

It would be easy to see this as simply a tale of gallant sacrifice — and it certainly is that. But there is another dimension that naval historians continue to point to.

Roope’s decision to ram and the damage inflicted meant that Admiral Hipper was out of action for approximately three months at a critical time in 1940. During that period, convoys sailed, troopships moved, and other naval operations took place without the threat of a modern German heavy cruiser intervening.

One destroyer that everyone expected to be lost anyway had, in effect, removed a much larger and more valuable ship from the playing board for a significant stretch of time.

From a purely strategic perspective:

One small ship

149 lives

Three months of reduced enemy capability

It’s not a barter anyone wants to make. But in the hard arithmetic of wartime, it mattered.

Why It Still Resonates

Today, the wreck of HMS Glowworm lies in deep, cold water off a small Norwegian island. It is a designated war grave, undisturbed.

The name has not been reused in the Royal Navy.

Instead, it stands alone: one ship, one action, one extraordinary moment.

Naval colleges and staff courses still study the engagement, not because anyone expects commanders to ram enemy cruisers as standard practice, but because it raises the kind of questions that matter when everything is going wrong:

What do you do when doctrine no longer applies?

How do you weigh certain loss against the chance to alter the situation, however slightly?

What does leadership look like when every option is terrible?

Roope’s choice will always be debated — tactically brilliant, or desperate? Brave, or unnecessarily costly? Perhaps, in truth, it was all of those things at once.

What is beyond debate is this:

He did not surrender.

He did not run.

He chose to act in a way that hurt the enemy and inspired his own men.

Even his opponent, Helmuth Heye, felt compelled to honor that.

In an age of missiles and screens, when naval combat can unfold beyond the horizon and out of sight, the story of HMS Glowworm and her final charge is a reminder that at the heart of every form of warfare are human beings — making decisions, taking risks, and sometimes choosing to do the unthinkable.

And that is why, more than eight decades later, we still tell the story of a small destroyer that rammed a heavy cruiser in a North Sea storm — and of the captain who decided, in his last minutes, that if his ship was going down, it would go down fighting.

News

The ‘What If’ Moment: Unmasking the U-Boat Ace Who Almost Flipped WWII in 30 Critical Seconds

In the spring of 1945, with the Second World War all but decided, a German submarine captain found himself in…

The Forbidden Weapon: How One Private Defied Orders, Used the ‘Wrong’ Grenades, and Became a Legend in the Pacific

In May 1944, on a coral island few Americans had ever heard of, a farm kid from Iowa quietly rewrote…

The Silent Steel Trap: This Underdog Weapon Decimated the U-Boat Fleet and Won the Battle of the Atlantic

In the early, uncertain years of the Second World War, the North Atlantic stopped being an ocean and became a…

The ‘Animal Hunter’s’ Day Job: Inside the Terrifying 152mm World of the ISU-152 Crew

The diesel cough from the engine swallowed the world, and for a moment the only thing that existed was metal,…

SENATE FLOOR SHATTERED: AOC’s ‘TIME IS OVER’ Declaration vs. Kennedy’s ‘Darlin’ Comeback’

The exchange was brief, the line was sharp, and within hours it had been replayed, reframed, and argued over in…

The Junkyard Miracle: How One Desperate WWII Pilot’s ‘DIY’ Bomb Flipped a Deadly Night Battle—The Improvised Device That Defied Science and Saved His Squadron, Leaving Enemy Aces Stunned. Uncover the Improbable Tale of the ‘Backyard’ Weapon That Re-Wrote Aviation History!

On a freezing December night in 1944, in a shallow shell crater outside a Belgian town called Büllingen, one American…

End of content

No more pages to load