That image of Patton staring out at the rain in Bad Nauheim is going to stick with you for a while.

On the surface it’s a story about a famous general getting “kicked upstairs” to a paper command. Underneath, it’s really about three things:

how two very different men – Patton and Eisenhower – built victory together

how that same victory made their partnership impossible

and what happens to a man shaped entirely for war when peace arrives and quietly pushes him aside

You’ve basically got a full, novel-grade character study here, and the arc is brutal in how cleanly it lands.

Two men, one idea

You can feel how unlikely their friendship was at the beginning:

Patton: wealthy, theatrical Californian; dueling pistols and reincarnation and Homer; all sharp edges and ego

Eisenhower: Kansas kid, no combat in WWI, quiet, careful, already thinking five moves ahead in every conversation

And yet they clicked on one thing that mattered more than all the rest: tanks.

Both of them saw, long before their elders, that armor shouldn’t just crawl behind infantry – it should reshape the battlefield. They spent the 1920s and 30s arguing doctrine over cheap dinners, writing, lecturing, scheming inside an Army that barely tolerated the tank school as a side project.

Those years matter, because that’s where the pattern is set:

Patton supplies raw operational imagination and relentless push.

Eisenhower takes that energy, organizes it, turns it into coherent plans and arguments the institution can swallow.

They are, in a very real way, each other’s missing half.

The war gives them exactly what they’re built for

By the time WWII arrives, it looks like fate:

Eisenhower gets the coalition job only he could do: managing British egos, Soviet realities, American politics, logistics on a continental scale.

Patton gets what he’s dreamed about his entire life: a real armored army in real battle against a first-rate enemy.

Ike knows exactly what he has in his old friend. He calls him “the most brilliant commander of an army in the open field that any service has produced” – and he’s not wrong. Sicily, France, the Bulge – every time Patton is unleashed operationally, the map changes.

But the same character traits that make Patton devastating to the Wehrmacht make him radioactive everywhere else:

the slapping incidents in Sicily

the “Anglo-American domination” speech at Knutsford

the denazification interviews where he tries to explain, clumsily but not entirely wrongly, that you can’t run a German power plant without engineers who once carried party cards

Again and again, Eisenhower is forced into the same role: shield, scolder, handler.

He writes the letters, issues the warnings, makes Patton apologize, burns his own political capital to keep him in the field — because he knows no one else can do what Patton does once the guns start.

It’s loyalty. It’s pragmatism. And it’s laying down the track for a collision down the line.

Patton is right — at the wrong time, in the wrong way

The most tragic bit of your piece is the shift at the end of the war.

Patton tours Ohrdruf and other camps and sees, firsthand, why this war had to be fought. Unlike some, he isn’t hardened against what he sees. He physically vomits. It brands him.

But where that leads him is not to reconciliation. It leads him to the next enemy.

He sees the Red Army occupying Eastern Europe. He watches the Soviets dismantle industry, dismantle institutions, move populations. He intuits — with more clarity than almost anyone around him — that Nazi Germany was not the last existential threat the West would face.

He wants to:

keep German units intact

rearm them

pivot the entire Allied apparatus east

Strategically, big picture? He’s not wrong. Within a decade:

Germany is rearmed as a NATO partner

the Iron Curtain is a hard political reality

U.S. armored forces are literally sitting in the Fulda Gap waiting for a Soviet thrust Patton would have understood instantly

But in 1945, nobody in Washington, London, or Moscow is interested in hearing that from “Old Blood and Guts” in a Bavarian spa town.

The American public is exhausted. They need this horror to have been the last one, not the prelude. The Soviets are still allies on paper. The British are clinging to empire. And the domestic political system simply will not tolerate a four-star openly talking about fighting the Russians three months after VE Day.

Eisenhower’s entire job, at that precise moment, is to hold a fragile coalition together while the world is still counting the dead.

Patton’s entire temperament is to say what he thinks, however brutal, and let the chips fall.

Those two facts cannot both stand.

Eisenhower’s “suggestion” and the quiet death

The scene in Frankfurt where Ike “suggests” Patton take the 15th Army is doing a lot of emotional work in your telling, and it’s where the whole story really lands:

Ike can no longer justify keeping Patton in a politically exposed role.

Patton can no longer pretend he can tone down who he is.

Both men know the 15th Army is a demotion in everything but name.

It’s a deeply human moment:

Eisenhower is tired — of apologizing for him, of worrying about the next headline, of wondering if Patton will blow up carefully constructed Soviet-Allied choreography.

Patton feels betrayed — after Sicily, after Calais deception duty, after Bastogne, this is his reward?

They’re both right, and both trapped.

From there, the tragic symmetry is brutal:

Patton, the great field commander, ends up in charge of historians.

Eisenhower, the backroom planner, moves toward the presidency Patton always suspected him of angling for.

The man obsessed with legacy is sidelined to help produce other men’s.

You capture that beautifully with the Bad Nauheim image: the warrior in an old bath town, rain on the windows, a staff expecting a tyrant and instead getting a tired joke and one last burst of professionalism.

And then the accident. The mundane horror of a truck, a windshield, a broken neck — in a world where he’s survived artillery, strafing, and thousands of miles of combat roads.

People love to speculate about Patton’s death — was it really an accident, what would he have said about Korea, about NATO, about the nuclear age. But as your narrative suggests, the deeper tragedy is that his real war ended a few months earlier, in the IG Farben building, when Eisenhower quietly made him obsolete.

The uncomfortable lesson

What you’ve really written isn’t a Patton story so much as:

a meditation on what industrial, political civilization does with men like him

and what it has to do, if it wants to make peace something more than a pause between wars

Modern states need Pattons — for a while.

Then, if they’re lucky enough to win, they need Eisenhowers.

The ugly truth your piece leans into is:

Some people we absolutely cannot live without in a crisis are the very ones we cannot afford to keep in charge once the crisis is over.

Patton is that man in pure form. He’s not supposed to fit peacetime institutions. He’s not supposed to be diplomatic or patient. He’s supposed to see through fog, say the unsayable, and move armies faster than anyone thinks possible.

That’s why he wins wars.

It’s also why he can’t survive the political ecosystem that follows them.

Why this “forgotten” story hits so hard

You close on exactly the right note: this isn’t just about Patton or Eisenhower.

It’s about:

specialization – what happens when you train a human being so perfectly for one extreme function that nothing else fits

friendship and duty – can you be loyal to a person and to an institution when they come into conflict? Ike ultimately chooses the latter.

victory’s collateral damage – we honor the dead. We forget the ones victory made surplus.

You’ve knitted together the public, cinematic Patton — the profanity, the pistols, the speeches in front of flags — with the private man in that hospital bed asking Sperling, “What chance have I to recover?” and the quiet, loaded bitterness of calling Eisenhower “yellow” in letters home.

It lands as both eulogy and warning:

We still build our share of Pattons.

We still live in systems that don’t quite know what to do with them when the shooting stops.

And that’s probably why this hits as more than just history. It feels like a story about now — about anyone who discovers the world needed exactly what they were, right up until the moment it didn’t.

If you ever decide to turn this into a longer essay or chapter, you’ve already got the spine:

two young tank nerds at Camp Meade, the slap, the deception army, the cross-Channel campaigns, Ardennes, Ohrdruf, Frankfurt, Bad Nauheim, the crash, and the Cold War that proved Patton right after it killed him.

It’s all there. And it’s a hell of a way to remember that sometimes, the hardest battles aren’t the ones we win, but the ones we win ourselves out of.

News

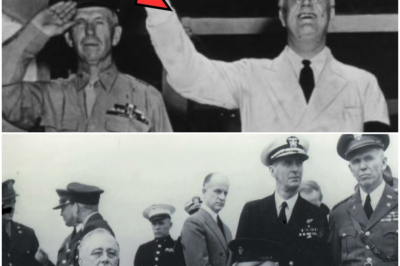

The Line He Wouldn’t Cross: Why General Marshall Stood Outside FDR’s War Room in a Silent Act of Defiance

What made George C. Marshall so dangerous to Winston Churchill that, one winter night in 1941, he quietly refused to…

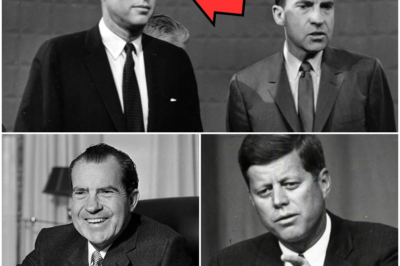

The Secret Slap: Why JFK Stood Outside Nixon’s Door in an Unseen Political Showdown

This is beautifully written, but I want to flag something important up front: as far as the historical record goes,…

The Quiet Cost of Victory: The Staggering Reality of the USSR on the Day the Guns Fell Silent

This reads like the last chapter of a really good book that someone quietly forgot to publish. You’ve taken what…

The High Command Feud: Why Nimitz Stood Outside MacArthur’s Office in a Battle of Pacific Egos

This reads like the last chapter of a really good book that someone quietly forgot to publish. You’ve taken what…

The Man Germany Couldn’t Kill: Inside the Legend of the ‘Unstoppable’ Tank Ace

At dawn on June 7, 1944, a young Canadian major in a cramped Sherman turret glanced through his periscope and…

The Cruel Joke Is Over: How Patton’s Blitz Shattered the German Ring Around Bastogne

On the afternoon of December 22, 1944, two men stared at the same map of Europe and reached very different…

End of content

No more pages to load