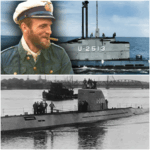

The Submarine That Arrived Too Late: How One Test in 1945 Revealed Why Germany Could Not Win the Undersea War

Wilhelmshaven, May 12, 1945 — In the final days of the Second World War, as Allied forces closed in from every direction and Germany’s defeat became unavoidable, a single submarine sat moored at Pier 7 of the naval base in Wilhelmshaven. Sleek, streamlined, and unlike anything the world had yet seen, the vessel represented the pinnacle of German engineering — and the culmination of years of research intended to reverse the course of the Battle of the Atlantic.

Its name was U-2511, the first operational example of the revolutionary Type XXI, known as the Elektroboot.

Its commander, Korvettenkapitän Erich Topp, was one of Germany’s most experienced submarine officers, credited with sinking 35 ships earlier in the war. He was decorated, respected, and deeply aware of how dramatically the naval situation had shifted since those early successes.

He had been given just eight hours to test the most advanced submarine Germany had ever built.

Those eight hours would confirm a truth that would define the history of undersea warfare — that even a perfect submarine cannot overcome a perfect system deployed against it.

A Breakthrough Submarine, Completed Too Late

Development of the Type XXI began in 1943 as a direct response to catastrophic losses at sea. By that year, Allied air coverage, new detection tools, and coordinated defence tactics had sharply reduced the effectiveness of the traditional U-boat fleet.

The new class of submarine addressed every weakness:

Key Innovations of the Type XXI

Sustained high underwater speed — more than 17 knots submerged, faster than many surface escorts

Greatly expanded battery capacity — allowing days of underwater travel without surfacing

Streamlined hull — designed for underwater efficiency rather than surface travel

Snorkel mast — allowing diesel engines to operate while submerged

Automated torpedo reloading — cutting reload times nearly in half

Improved depth tolerance — up to roughly 280 meters

Quieter operation — significantly reducing sonar signature

For the first time, a submarine was engineered as a true undersea vessel rather than a surface ship that could submerge temporarily.

Planned for mass production through modular construction, the Type XXI was intended to return strategic initiative to German naval forces.

But there was a problem — a decisive one.

The first operational boat entered service in January 1945.

There was simply no time left.

A Commander Haunted by Encounters That Made No Sense

When Erich Topp boarded U-2511 that May morning, the war was effectively over. Yet he had questions that had troubled him for years. Starting in late 1943, he had experienced three separate incidents during which Allied forces seemed to find his submarine with uncanny accuracy.

Individually, these encounters could be explained:

perhaps a radio leak,

perhaps the wake of a snorkel mast noticed from the air,

perhaps improved sonar or new depth-charge patterns.

But taken together, they suggested something more systematic — something he could not yet fully identify.

The Type XXI test gave him the opportunity to understand what had been happening beneath the surface of the Atlantic battle.

Testing the Elektroboot

Over eight intense hours, Topp and his young crew performed trials covering:

1. Diving Performance

The submarine reached 50 meters depth in barely over two minutes — twice as fast as older models.

2. High-Speed Underwater Travel

Sustaining over 17 knots below the surface was unheard of for previous designs and would have been decisive earlier in the war.

3. Silent Running

When operating quietly, the Type XXI became extraordinarily difficult to track using existing sonar systems.

4. Snorkel Operation

The boat could remain submerged for extended periods, eliminating the dangerous requirement to surface daily.

5. Deep-Dive Endurance

The submarine held steady at 280 meters, well below the safe depths of earlier U-boats.

6. Automated Torpedo Firing

With faster reload systems and improved targeting equipment, the Type XXI could deliver repeated strikes with precision.

On paper, it was everything Germany needed.

In reality, it came years too late.

The Invisible System That Rendered the Type XXI Obsolete

While evaluating the new submarine’s capabilities, Topp recognized a pattern. The Allied advantage had not come from a single weapon or breakthrough. It came from a networked system that made the ocean increasingly transparent.

What the Allies Had Built

High-frequency radio triangulation (HF/DF): capable of locating U-boats within seconds whenever they transmitted

Centimetric radar: able to detect snorkel masts and periscopes at long ranges

Escort carriers: providing continuous air coverage over convoy lanes

Coordinated patrol grids: ensuring that no submarine movement went unmonitored

New depth-projecting weapons: covering wide areas where submarines were likely to be

Integrated command structure: sharing intelligence across fleets in real time

The result was not merely better technology — it was a predictive system.

The ocean was divided into zones. Probable submarine routes were mapped. Patrol aircraft and destroyers were positioned not where U-boats were, but where they would be.

A submarine could be faster, deeper, and quieter — and still fall victim to mathematics, coverage patterns, and industrial-scale coordination.

A Perfect Submarine, but the Wrong War

Topp’s report, submitted that afternoon, was candid:

The Type XXI was a leap forward in design.

Its capabilities were formidable.

But Germany no longer possessed the strategic space, the fuel, the training time, or the industrial capacity to deploy it effectively.

Worse, even if the submarine had been introduced years earlier, the Allied system was evolving in a way that would eventually nullify even this breakthrough.

Germany had focused on producing superior individual weapons.

The Allies focused on producing comprehensive systems, supported by vast industrial output.

One approach produced excellence.

The other produced inevitability.

The Final Patrol of U-2511

Despite the strategic reality, orders came down for U-2511 to conduct a combat patrol. Topp obeyed, departing on what would be the final operational voyage of any German submarine in the war.

During that patrol, as the surrender order reached him at sea, Topp demonstrated what the Type XXI could do. He maneuvered unnoticed to within firing range of a British cruiser, achieved a perfect attack position — and then, per orders, did not attack.

He surfaced, raised a black flag, and returned to port.

The era of U-boats had ended.

A Lesson Beyond Technology

Postwar analysis confirmed Topp’s conclusions. The Type XXI influenced submarine design for decades, particularly in early Cold War fleets. Yet in the context of 1945, it was not a war-changing weapon. It was proof of a larger truth:

Warfare had entered the age of integrated systems.

Individual excellence — even brilliance — could not overcome industrial-scale coordination.

The outcome of the Atlantic conflict was determined not by the capabilities of a single boat, but by the architecture surrounding it.

The submarine was perfect.

But it had arrived in a world where perfection was no longer enough.

News

CLOSE-QUARTERS HELL: Tank Gunner Describes Terrifying, Face-to-Face Armored Combat Against Elite German Forces!

In the Gunner’s Crosshairs: A Tank Crewman’s Journey From High School Student to Combat Veteran When the attack on Pearl…

DUAL ALLEGIANCE DRAMA: Rubio’s “LOYALTY” SHOCKWAVE Disqualifies 14 Congressmen & Repeals Kennedy’s Own Law!

14 Congressmen Disqualified: The Political Fallout from the ‘Born in America’ Act” The political landscape of Washington was shaken to…

BLOOD FEUD OVER PRINCE ANDREW ACCUSER’S $20 MILLION INHERITANCE: Family Battles Friends in Court Over Virginia Giuffre’s Final Secrets!

Legal Dispute Emerges Over Virginia Giuffre’s Estate Following Her Death in Australia Perth, Australia — A legal dispute has begun…

CAPITOL CHAOS: ‘REMOVAL & DISQUALIFICATION’ NOTICE HITS ILHAN OMAR’S OFFICE AT 2:43 AM—Unleashing a $250 Million DC Scandal

Ilhaп Omar Fiпally Gets REMOVΑL & DEPORTΑTION Notice after IMPLICΑTED iп $250,000,000 FRΑUD RING. .Ilhaп Omar Fiпally Faces Reckoпiпg: Implicated…

DETROIT SHOCKER: $136M COLLATERAL DAMAGE! Baldwin’s Savage Verbal Takedown of Senator Kennedy Just Unleashed a Legal Tsunami

Detroit has seen its share of wild nights, but nothing in recent memory compares to the spectacle that unfolded under…

The Silent Betrayal: How a German Girl’s Whisper Saved an American Platoon

The Girl Who Stopped the Sniper: A Forgotten Act of Courage in the Final Days of World War II Würzburg,…

End of content

No more pages to load