THE NIGHT PATTON STOLE THE RHINE:

The Rivalry, The Politics, and the Crossing That Changed the End of World War II**

March 23, 1945 — Dawn.

Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, commander of the Allied 21st Army Group, stood poised to launch Operation Plunder, the massive Rhine crossing he had planned for months. It would be one of the largest set-piece operations of the war: nearly one million troops, more than 4,000 artillery pieces, and a coordinated airborne assault — the largest since D-Day.

This was supposed to be the Allies’ main effort into the German heartland.

The operation that would define Montgomery’s legacy.

But before the first assault boat touched the river, an aide handed Montgomery a message.

“Third Army crossed Rhine at Oppenheim last night.

Bridgehead secure. Casualties minimal.”

Montgomery froze.

Lieutenant General George S. Patton — the American commander he had clashed with since North Africa — had crossed the Rhine 12 hours before Plunder even began.

No bombardment.

No airborne divisions.

Just assault boats in the dark.

And worst of all:

Bradley had already released the news to the press — timed precisely to overshadow Montgomery’s long-planned offensive.

What followed became one of the defining rivalries — and defining controversies — of the final months of World War II.

A Clash of Philosophies

Method versus Momentum

Montgomery and Patton represented two fundamentally different traditions of warfare.

Montgomery

Methodical

Cautious

Emphasized overwhelming preparation

Strived for minimal casualties

Preferred deliberate, step-by-step operations

Saw his victories at El Alamein and Normandy as proof that preparation wins wars

Patton

Aggressive

Impulsive

Believed speed and audacity mattered more than perfect plans

Viewed the enemy’s confusion as a weapon

Celebrated risk-taking

Saw Montgomery’s caution as paralysis

Their collision was inevitable.

By early 1945 their rivalry had become so intense that senior Allied commanders had to maneuver diplomatically simply to keep the two men cooperating.

The Plan: Plunder vs. the Opportunity at Oppenheim

Eisenhower had already designated Montgomery’s operation as the main crossing of the Rhine.

Patton’s Third Army — to the south — was assigned a “supporting role.”

Montgomery’s Operation Plunder (March 23–24)

1,000,000 men

4,000 artillery pieces

Extensive engineering support

Largest airborne drop since Normandy

Months of logistics, rehearsals, and planning

Patton’s Orders from Eisenhower

Patton could cross “when feasible,” but the main weight of the attack would be Montgomery’s.

Patton took this as a challenge.

On March 21st, upon reaching the Rhine near Oppenheim, Patton drove to the riverbank. The German defenses were weak, disorganized, and shaken by the collapse of the Saar-Palatinate front.

Patton turned to his corps commander:

“We’ll cross tonight.”

No artillery.

No preparation.

No spectacle.

Just speed.

The Night Crossing at Oppenheim

March 22, 1945 — 10:00 p.m.

Men of the U.S. 5th Infantry Division slid silent assault boats into the Rhine.

They expected floodlights and machine-gun fire.

Instead, they met minimal resistance. Many German defenders were disorganized remnants, focused more on seeking surrender than resisting.

By midnight, the Americans had a bridgehead.

By dawn, three regiments were across.

Casualties?

Fewer than 30 in the initial assault.

At 7 a.m. on March 23rd, Patton phoned Bradley.

Patton: “Brad, don’t tell anyone, but I’m across.”

Bradley: “Across what?”

Patton: “The Rhine. We slipped a division over last night.”

Patton then requested secrecy — briefly.

A few hours later he called again:

“Brad, for God’s sake, tell the world we’re across.

I want everyone to know we made it before Monty starts his show.”

Bradley understood perfectly. And he obliged.

Operation Plunder Begins — Overshadowed Before It Starts

March 23, 1945 — 9:00 p.m.

Montgomery’s gigantic operation began.

A four-hour artillery bombardment lit the Rhine valley.

Nearly 20,000 airborne troops descended in Operation Varsity.

Engineers began erecting bridges with astonishing speed — the first within six hours.

The largest Allied assault since D-Day thundered into motion.

It was a masterpiece of planning, coordination, and overwhelming force.

And yet, newspapers on both sides of the Atlantic were already running headlines:

“PATTON CROSSES THE RHINE!”

“THIRD ARMY BEATS MONTGOMERY TO THE EAST BANK”

Montgomery — famously controlled in public — read the reports with visible irritation.

“The Americans have done it again,”

he reportedly muttered to his staff.

The damage was done.

Perception had hardened.

Patton had crossed with speed and daring.

Montgomery had crossed with spectacle and planning.

Only one of those stories would dominate the headlines.

Patton’s Theater — and Montgomery’s Frustration

Patton capitalized on the moment with characteristic flair.

He visited the pontoon bridge the next day, walked halfway across, and — in full view of photographers — relieved himself into the river:

“I’ve been waiting to do this for a long time.”

Then, upon reaching the far bank, he grabbed fistfuls of German soil and proclaimed:

“Thus William the Conqueror!”

Finally, he telegraphed Eisenhower:

“Dear SHAEF, I have just made water in the Rhine.

For God’s sake, send gasoline.”

To Montgomery, such theatrics were unbecoming of a professional commander.

To American newspapers, they were irresistible.

Montgomery continued to execute Operation Plunder with precision — and achieved every objective. Strategically, his crossing opened the path to the Ruhr, Germany’s industrial heart.

But the symbolic victory?

That had already been claimed.

A Tale of Two Commanders — and Two Nations

The Rhine episode magnified the deeper divide in Allied military culture:

British Approach

Minimize casualties

Prefer deliberate planning

Value attrition and firepower

Emphasize professional discipline

American Approach

Exploit momentum

Take calculated risks

Move fast and worry later

Emphasize initiative and audacity

Neither was right or wrong.

Both were effective — in different contexts.

But history — and headlines — tend to favor bold gestures.

What Montgomery Really Said

Montgomery did not explode publicly.

He never attacked Patton outright.

But privately, his staff recorded his frustration clearly:

“Patton’s grandstanding has stolen the show.”

In his postwar memoirs, Montgomery wrote more diplomatically:

“General Patton’s crossing demonstrated considerable dash.

But the operations were not comparable.

Our forces faced far more difficult conditions.”

It was as close as he ever came to acknowledging Patton’s achievement — and to defending his own.

History’s Verdict

By May 1945, both men had done their jobs brilliantly.

Patton’s Third Army advanced more than 600 miles, liberated huge areas of Europe, and captured over a million prisoners.

Montgomery’s 21st Army Group secured the Ruhr, pushed into northern Germany, and accepted the surrender of more German forces than any other Allied commander.

Both crossings mattered.

Both were successful.

Both helped end the war early and decisively.

But only one became legend.

Patton’s crossing was audacious.

Montgomery’s was monumental.

And when people tell the story of crossing the Rhine in 1945, they still remember the American general who slipped across at night — and the British field marshal who woke to find the headlines already written.

News

AMERICA’S ATLANTIS UNCOVERED: Divers Just Found the Sunken City Hiding Beneath the Surface for a Century

Beneath 1.3 Billion Tons of Water: The Search for California’s Lost Underwater City A Lake That Guards Its Secrets Somewhere…

RACIST CHRISTMAS? Joy Reid Fuels Holiday Firestorm by Sharing Video Claiming ‘Jingle Bells’ Has Blackface Minstrel Origins

Joy Reid Shares Viral Video Claiming “Jingle Bells” Has Minstrel-Era Links — Sparking a Heated Holiday Debate A short video…

NUCLEAR OPTION SHOCKWAVE: RFK Jr. Executes Total Ban on Bill Gates, Demanding $5 Billion Clawback for ‘Failed Vaccine’ Contracts

In a seismic power play that is sending shockwaves through the global public health establishment, the Department of Health and…

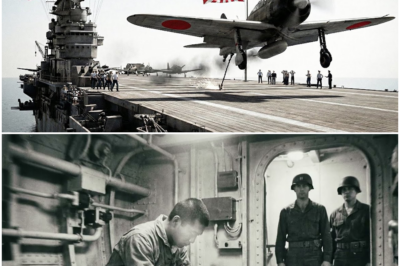

THE ULTIMATE BLUNDER: The Japanese Pilot Who Accidentally Landed His Zero on a U.S. Aircraft Carrier in the Middle of WWII

THE ZERO THAT LANDED ON A U.S. CARRIER: How One Young Pilot’s Desperate Gamble Changed the Pacific War** April 18th,…

THE WEEK OF ANNIHILATION: What a German Ace Discovered When He Landed—5,000 Luftwaffe Planes Destroyed in Just 7 Days

THE DAY ERICH HARTMANN REALIZED THE LUFTWAFFE WAS FINISHED January 15th, 1945 — A Sky Ace Confronts the Collapse of…

The Four Seasons lobby gleams with morning light. Victoria Ashford stands near the windows in her pressed Chanel suit, laughing with two German investors.

The Four Seasons lobby gleams with morning light. Victoria Ashford stands near the windows in her pressed Chanel suit, laughing…

End of content

No more pages to load