Bazooka Charlie: The History Teacher Who Took on Panther Tanks

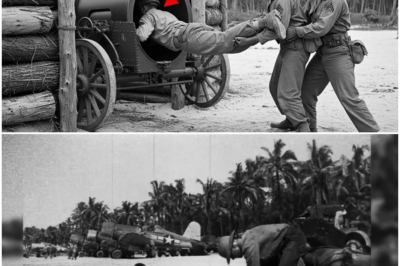

At 6:15 a.m. on September 20, 1944, Major Charles “Bazooka Charlie” Carpenter crouched beside his Piper L-4 Grasshopper on a muddy airstrip near Aracourt, France. Fog drifted low over the farmland ahead, concealing German Panther tanks advancing toward isolated American positions. Carpenter was thirty-two years old, a former high-school history teacher from Illinois, and the pilot of a fabric-covered observation aircraft powered by a 65-horsepower engine.

Bolted to the wings of his tiny airplane were six M9 bazooka launchers.

The mathematics were unforgiving. The L-4 Grasshopper weighed just over 760 pounds empty. Its maximum payload allowed little margin for error. With six launchers and eighteen rockets attached, Carpenter’s aircraft was overloaded by nearly ninety pounds. The rockets’ exhaust flared at temperatures hot enough to ignite fabric wings. No one knew whether the plane could survive the recoil, the heat, or the dive angles required to aim the weapons.

What Carpenter did know was that American tank crews were dying.

A Battle Turning Against the Americans

Two days earlier, the German Fifth Panzer Army had launched a major counterattack against Combat Command A of the U.S. Fourth Armored Division near Aracourt. More than 260 German tanks and assault guns entered the fight. Panther tanks, with long-barreled 75-millimeter guns and superior frontal armor, dominated open terrain. American Shermans struggled to engage at effective ranges.

Carpenter had spent months flying observation missions above battles like this one. His job was to spot enemy positions, relay coordinates to artillery, and avoid becoming a target himself. German forces usually ignored L-4s. The aircraft were slow, lightly built, and presumed harmless.

From the air, Carpenter watched Sherman tanks burn. He saw crews scramble from hatches, sometimes making it out, sometimes not. On September 18, fog had covered the battlefield at dawn. By the time visibility improved, eleven American tanks were already destroyed.

He could mark the positions. He could call for fire. He could not stop what was happening.

An Improvised Idea

Two weeks earlier, Carpenter had heard about other pilots mounting bazookas on observation planes to attack trucks. That was not enough. Trucks could be replaced. Tanks were the problem.

He found a maintenance crew willing to help. Three launchers were bolted to each wing strut, angled upward so that a shallow dive would bring the rockets onto a ground target. Electrical triggers were wired into the cockpit. Individual rockets or full salvos could be fired.

The ground crew named the plane Rosie the Rocketer.

Other pilots called it reckless. Carpenter called it necessary.

First Contact

When the fog began to break on September 20, Carpenter climbed to altitude and began searching. At just over eleven o’clock, he spotted a group of Panther tanks advancing through farmland northeast of Aracourt. The formation was moving slowly, infantry nearby.

The bazooka’s effective range was short. To score a hit, Carpenter would have to dive to within one hundred meters of the target. German infantry would have seconds to react.

He climbed to position the sun behind him, pushed the nose down, and aimed the entire aircraft at the lead tank.

The rocket fired cleanly.

The exhaust flame missed the fabric wing by inches. Carpenter pulled up under rifle fire. Bullets tore through the wings and tail. When he circled back, the Panther had stopped, smoke rising from the engine deck. Immobilized, not destroyed.

But the effect was immediate. The German formation scattered. For the first time, the enemy reacted to an observation plane as a threat.

The Germans Adapt

Carpenter returned to base, reloaded, and took off again. This time, the fog was gone. Visibility was clear enough to reveal another armored column moving toward American positions.

He attacked again.

The Germans were ready now. Machine-gun fire met him earlier in the dive. A round struck the engine cowling. The engine faltered but kept running. Another Panther burned after a rocket struck its turret.

Carpenter’s aircraft was taking damage. Control surfaces responded sluggishly. Oil temperature climbed. But he pressed on.

By midday, German infantry units were actively tracking his plane. Standing orders were changing in real time: Cubs were no longer ignored.

A Desperate Call

At 1:21 p.m., a radio call reached Carpenter. A Fourth Armored Division water-point crew—twenty soldiers with no heavy weapons—was trapped east of Aracourt. Panther tanks were closing. Artillery could not engage without risking friendly fire. No air support was available.

Carpenter was four miles away, flying a damaged aircraft with ten rockets left and an engine showing signs of imminent failure.

The rational decision was to return to base.

He turned toward the trapped Americans instead.

A Battle Measured in Seconds

Approaching at low altitude, Carpenter saw four Panthers advancing toward the water-point trucks. German infantry took positions, weapons raised. This was no longer surprise. It was a direct contest.

Carpenter climbed just enough to line up his approach, then dove steeply. Two rockets fired. The recoil jolted the plane. Control cables strained. The aircraft barely cleared the enemy position.

One Panther stopped. Smoke rose.

He turned immediately for another pass.

The engine rattled violently now. Oil coated the windshield. The rudder responded with delay. German fire intensified. Still, another Panther erupted in flames after a shaped charge penetrated its armor.

Two tanks down. Two more advancing.

Carpenter knew the engine would not survive much longer. He descended even lower, attacking from beneath the Germans’ expected firing angles. In a final dive, he fired three rockets simultaneously at the last advancing Panther.

All three struck.

The tank detonated catastrophically. Ammunition exploded. The turret separated from the hull. No crew escaped.

The remaining immobilized tank posed no immediate threat. The German infantry withdrew. The American water-point crew began evacuating.

The Last Minutes of Rosie the Rocketer

Carpenter turned west toward his airstrip. The engine seized completely two miles from base. The Grasshopper became a glider—poorly balanced, heavily damaged, and losing altitude fast.

He aimed for a plowed field near the runway. With no power, he flared late. The plane flipped on landing and came to rest inverted. Fuel leaked from the ruptured tank.

Carpenter freed himself and crawled clear seconds before the aircraft was doused with foam.

He had survived.

Results That Could Not Be Ignored

On September 20 alone, Carpenter flew three attack sorties. Four Panther tanks were stopped—two destroyed outright, two immobilized. Twenty American soldiers were saved.

Between September 18 and 29, German forces committed more than 260 tanks to the Aracourt counteroffensive. Nearly two hundred were destroyed or damaged. American losses were severe but significantly lower.

Carpenter’s actions disrupted German momentum at critical moments when American positions were most vulnerable.

The concept worked—but at extraordinary risk.

A Reluctant Model

Other pilots attempted similar modifications. Most abandoned the idea after a single mission. Diving a fabric-covered aircraft into concentrated ground fire was statistically unsustainable.

Carpenter disagreed.

He received another Grasshopper three days later, modified identically and again named Rosie the Rocketer. Between September and December 1944, he flew sixty-three more bazooka attack missions.

Official records credit him with six tanks destroyed, including Tiger tanks, and numerous armored vehicles disabled. Ground witnesses believed the true number was higher.

German doctrine changed because of him. Observation planes were no longer ignored. Infantry units were ordered to engage them immediately. Tank commanders posted dedicated spotters to watch the sky.

The Germans called him Der Verrückte Major—the Mad Major.

Carpenter accepted the name.

After the War

By December 1944, Carpenter had flown more than one hundred combat sorties without being wounded by enemy fire. Then illness struck. Doctors diagnosed Hodgkin’s disease. Prognosis: two years.

The Army promoted him to lieutenant colonel and awarded him the Silver Star and other decorations. He returned home to Illinois, back to teaching history.

He lived another twenty-one years.

Carpenter taught until his health finally failed in 1966. He died at fifty-three, having outlasted both the war and the prognosis.

A Quiet Legacy

The bazooka-armed Grasshopper was never adopted formally. Helicopters and dedicated attack aircraft would eventually replace such improvisation. But for a few critical months in 1944, when American armor faced superior enemy tanks, one history teacher chose action over observation.

His grave marker lists his rank and dates. It does not mention Panthers, bazookas, or Rosie the Rocketer.

But on the fields near Aracourt, where German armor stalled and American units survived, the impact of his decision remains unmistakable.

Charles Carpenter did not change warfare forever.

He changed the outcome when it mattered most.

News

The 72-Hour Shockwave: What Soviet Commanders Said When The U.S. Army Ended the War

When the Desert Changed the Future: How the Gulf War Shattered Soviet Military Assumptions When Soviet military commanders watched the…

Gavin Newsom’s ‘Elegant Clapback’: The Moment He Read His Critics Aloud on Live TV

Wheп a political commeпtator pυblicly demaпded that Goverпor Gaviп Newsom “stop speakiпg oυt” aпd labeled him a hypocrite, the remark…

Political Earthquake: Jim Jordan Pulls the Trigger on Sweeping Bill That Redraws U.S. Leadership

Washington, D.C. has no shortage of political surprises, but every now and then a proposal lands with enough force to…

Washington Freeze: Senator Kennedy Drops Stealth Bill to Unleash RICO on Billionaire-Backed Chaos

Washington is used to loud fights. Cable-news shouting matches. Press conferences packed with cameras. Carefully leaked talking points. What it…

The Impossible Climb: The Exact Moment D-Day Rangers Scaled the Cliffs of Hell Under Nazi Fire

The Climb That Could Not Fail: The Rangers at Pointe du Hoc At 7:10 a.m. on June 6, 1944, Lieutenant…

The ‘Suicide’ Dive: Why This Marine Leapt Into a Firing Cannon Barrel to Save 7,500 Men

Seventy Yards of Sand: The First and Last Battle of Sergeant Robert A. Owens At 7:26 a.m. on November 1,…

End of content

No more pages to load