Seventy Yards of Sand: The First and Last Battle of Sergeant Robert A. Owens

At 7:26 a.m. on November 1, 1943, the landing at Cape Torokina on the island of Bougainville began as planned. American naval gunfire had battered the shoreline for more than an hour, and intelligence assessments predicted only light resistance. What followed instead was paralysis.

From a coconut log bunker concealed just fifty yards up the beach, a Japanese 75-millimeter mountain gun opened fire. Within minutes, landing craft were burning in the shallows. Marines were pinned down in knee-deep water. The beachhead—critical to isolating the powerful Japanese base at Rabaul—was collapsing before it had fully formed.

By 8:00 a.m., one artillery piece had destroyed four landing craft, damaged ten more, and halted the movement of roughly 7,500 Marines. Naval gunfire could not be used without risking friendly casualties. Infantry weapons could not penetrate the bunker’s thick coconut-log walls. Grenades detonated harmlessly on the roof. The gun continued firing with mechanical regularity.

The landing was failing because of one position.

Sergeant Robert Allan Owens was watching it happen.

A Marine With No Combat Experience

Owens was twenty-three years old. He had trained for nearly two years, but had never seen combat. Born in Greenville, South Carolina, he left school early and spent five years working in textile mills in Spartanburg. After Pearl Harbor, he enlisted in the Marine Corps in February 1942.

His training took him from Parris Island to advanced infantry instruction in North Carolina, then across the Pacific to Samoa, New Zealand, and finally Guadalcanal for final preparation. His unit—Company A, 1st Battalion, 3rd Marines—was part of the 3rd Marine Division, assigned to land at Cape Torokina as the opening move in the campaign to neutralize Rabaul.

The plan relied on speed. Marines would seize a beachhead, build airstrips, and bring Rabaul under constant air attack without a costly direct invasion. That plan was unraveling in real time.

A Problem Without a Solution

From his position behind a sand dune, Owens studied the bunker. He counted the firing pattern: eight rounds per minute. He noted reload times and barrel movement. He watched more Marines pull wounded men out of the surf.

Rifles could not stop the gun. Grenades could not stop it. Naval fire could not be used. If the gun continued firing, the landing would stall, ships would withdraw, and the entire operation could fail.

Owens made a decision that did not involve orders or consultation.

He asked for volunteers to suppress nearby bunkers. Four Marines stepped forward. Owens positioned them, explained his plan, and prepared to attack the gun head-on.

The distance was seventy yards of open volcanic sand. There was no cover. The gun crew would see him immediately.

The Charge

Owens waited for the gun to fire, then ran.

The bunker crew spotted him at once. The barrel began traversing, abandoning its firing rhythm to track a single Marine. At forty yards, Owens could see the muzzle. At thirty yards, the gun fired. The shell detonated close enough to knock him sideways.

He kept running.

At ten yards, the gun fired again. The blast passed so close that Owens felt the pressure wave. He reached the bunker wall as the crew began reloading.

Instead of retreating, Owens climbed into the firing port itself.

The opening was narrow, designed for a gun barrel, not a man. The weapon was still loaded. Inside, the crew was preparing for close combat. Owens forced his way through the opening under fire, burning himself on the hot barrel as he squeezed inside.

The Japanese artillery crew broke and fled through the rear exit.

Beyond the Bunker

Silencing the gun was not enough. If the crew returned, the weapon could be put back into action.

Owens pursued them into the trench system behind the bunker.

What followed was a series of close-quarters engagements fought in narrow, zigzagging trenches. Owens moved alone, navigating unfamiliar terrain, engaging multiple enemy soldiers, and using grenades and rifle fire to eliminate resistance.

He was wounded during the pursuit—first in the shoulder, then more severely in the chest—but continued forward. One by one, he killed the remaining members of the gun crew, ensuring none could return to the artillery piece.

By the time the final crew member fell, Owens had accounted for all five men who had operated the gun.

Behind him, the beach fell silent.

The Landing Resumes

With the 75-millimeter gun permanently silenced, adjacent Japanese positions soon collapsed. Marines began moving inland. Landing craft resumed their runs. By mid-morning, the beachhead was secure.

Owens, bleeding heavily, attempted to withdraw. He was confronted by additional Japanese soldiers emerging from the trench network. Wounded and nearly out of ammunition, he fought on, killing several more attackers before being struck fatally.

He died alone beneath a palm tree, pistol still in hand.

Discovery and Assessment

Corporal James Mitchell found Owens’s body hours later during a patrol. The scene told the story clearly: multiple enemy dead, grenade pins, spent casings, a blood trail leading from the bunker into the trench system.

The timeline was precise. The gun had ceased firing at 8:52 a.m. It was never recaptured. By 9:30 a.m., landing craft were reaching the shore unopposed.

The mathematics were stark. Half of the division—approximately 7,000 Marines—had not yet landed when Owens charged the bunker. Without that action, the landing could have stalled long enough for Japanese air forces from Rabaul to strike the beachhead before defenses were established.

Owens had bought time. Time measured in lives.

Strategic Consequences

Cape Torokina was secured by nightfall. Engineers began constructing airstrips almost immediately. Within weeks, American aircraft were operating from Bougainville, bringing Rabaul under constant attack.

The Japanese base, once the most powerful naval stronghold in the South Pacific, was neutralized without direct invasion. More than 100,000 Japanese troops were isolated and rendered operationally irrelevant.

This outcome traced back to the opening hours of November 1, 1943—and to the silence of one gun.

Recognition

Major General Allen Turnage recommended Owens for the Navy Cross. The citation emphasized that no single act had saved more lives or contributed more directly to the success of the landing.

When the recommendation reached Marine Corps Commandant Alexander Vandegrift, he requested the case be reviewed for the Medal of Honor. After extensive investigation, including witness statements and captured enemy records, the award was approved.

On August 12, 1945, the Medal of Honor was presented posthumously to Owens’s family.

Memory and Meaning

Owens was buried at the Manila American Cemetery. A U.S. Navy destroyer later bore his name, serving for twenty-five years across multiple conflicts.

Yet beyond citations and names, the deeper cost remains harder to quantify.

Owens was twenty-three years old. He had lived an ordinary life before the war. He worked in a textile mill. He had family, routines, and a future that did not include a bunker on a distant beach.

What he gave up was not only his life, but everything that life would have contained.

The Quiet Beach

Most Marines who came ashore after the gun fell silent never knew why the beach was quiet. They did not know Owens’s name. They only knew they could move forward.

That is often how such acts endure—not as stories known to all, but as absences of catastrophe, as disasters that never happened.

On November 1, 1943, one gun stopped firing.

And because of that silence, thousands of men lived to fight another day.

That is the legacy of Sergeant Robert A. Owens.

News

The Impossible Climb: The Exact Moment D-Day Rangers Scaled the Cliffs of Hell Under Nazi Fire

The Climb That Could Not Fail: The Rangers at Pointe du Hoc At 7:10 a.m. on June 6, 1944, Lieutenant…

Crisis Point: Ilhan Omar Hit With DEVASTATING News as Political Disasters Converge

Ilhan Omar Hit with DEVASTATING News, Things Just Got WAY Worse!!! The Walls Are Closing In: Ilhan Omar’s Crisis of…

Erika Kirk’s Emotional Plea: “We Don’t Have a Lot of Time Here” – Widow’s Poignant Message on Healing America

“We Don’t Have a Lot of Time”: Erika Kirk’s Message of Meaning, Loss, and National Healing When Erika Kirk appeared…

The Führer’s Fury: What Hitler Said When Patton’s 72-Hour Blitzkrieg Broke Germany

The Seventy-Two Hours That Broke the Third Reich: Hitler’s Reaction to Patton’s Breakthrough By March 1945, Nazi Germany was no…

The ‘Fatal’ Decision: How Montgomery’s Single Choice Almost Handed Victory to the Enemy

Confidence at the Peak: Montgomery, Market Garden, and the Decision That Reshaped the War The decision that led to Operation…

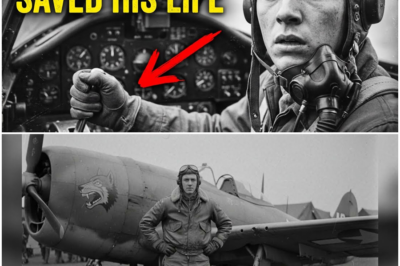

‘Accidentally Brilliant’: How a 19-Year-Old P-47 Pilot Fumbled the Controls and Invented a Life-Saving Dive Escape

The Wrong Lever at 450 Miles Per Hour: How a Teenager Changed Fighter Doctrine In the spring of 1944, the…

End of content

No more pages to load