THE LAST THREE SECONDS:

Private First Class Harold Gonzalez and the Forward Observers Who Broke the Defenses of Mount Yayatake**

On April 15, 1945, at 07:30, Private First Class Harold Gonzalez crouched behind a jagged volcanic outcrop on the lower slopes of Mount Yayatake, Okinawa. He was nineteen years old, fourteen days into the campaign, and had not yet completed a single mission that hadn’t ended with Marines dead or wounded.

Ahead of him, Japanese mortar rounds were bursting across the hillside where his forward observer team was attempting to direct artillery fire. Behind him, the Sixth Marine Division was locked in a grinding ascent—progress measured in yards, casualties in dozens.

Mount Yayatake dominated the Motobu Peninsula, and Colonel Udo’s force of roughly 1,500 Japanese soldiers had transformed it into a fortress of fortified caves, concealed gun pits, spider holes, and cleverly camouflaged reverse-slope defenses. Whoever controlled its summit controlled the northern approaches to Okinawa’s landing beaches. For the Marines, taking the mountain was not optional.

Gonzalez belonged to Battery L, 4th Battalion, 15th Marines—a forward observer detachment whose task was simple on paper and deadly in practice:

get close enough to the Japanese lines to spot enemy positions, relay precise coordinates by field telephone, and adjust fire.

But on Okinawa’s volcanic slopes, “close enough” meant within 200 yards of the enemy, sometimes within grenade range.

Forward observation was one of the most dangerous duties on the battlefield. In the first three days of the assault, seven teams had been sent forward. Five were forced back. Two got into position. Both suffered casualties. One lost its radio operator to a sniper. The other lost its officer to a mortar round that landed fifteen feet from their post.

Still, the infantry could not advance without artillery. Artillery could not be effective without observers.

The chain held only if its most fragile link remained in place.

Gonzalez had volunteered for this duty months earlier—Guadalcanal, Eniwetok, Guam. Enough fighting to know what got men killed. Enough to volunteer anyway.

The Mission Begins

The assignment that morning was clear:

• advance several hundred yards up the mountain’s eastern slope,

• establish a new observation post,

• run field telephone wire back to the battalion fire direction center,

• and call fire on Japanese positions before the Marine infantry attacked in four hours.

Radio signals were unreliable here—caves, cliffs, and shattered terrain swallowed transmissions. The only guaranteed link to the artillery batteries three miles behind the lines was copper telephone wire, laid by hand.

At 07:55, American 105mm guns opened their preparatory barrage. The officer gave the signal. The three-man team rose and moved into the smoke-shrouded slope—Gonzalez carrying one spool of field wire, the third Marine carrying another.

They advanced during the bombardment, using its thunder to mask their movement. But as soon as the guns shifted their fire higher up the mountain, the sudden silence announced danger more clearly than any rifle shot.

A single Japanese bullet cracked into a rock near the officer’s feet. No follow-up shot—just a warning.

The enemy had seen them.

Mortar fire followed. Accurate. Bracketing. Closing.

The team sprinted the last yards into a shallow depression—their first planned observation point—just as a 70mm mortar round detonated where they’d been standing seconds before.

Inside the crater they caught their breath, then lifted binoculars over the rim.

The Japanese were far closer than intelligence had suggested.

Within 160 yards lay a network of rifle pits, machine-gun bunkers with interlocking fields of fire, mortar pits set back under camouflage netting, and—worst of all—cave entrances masking reverse-slope assembly areas.

Artillery had done little to them. Log-reinforced roofs and deep tunnels had shrugged off anything but a direct hit.

Now it fell to the observers to correct that.

The officer connected the telephone line, established contact, and began calling the first fire missions. The howitzers responded. Shells walked across the ridge line, collapsing a machine-gun nest and ripping open a trench.

But they needed to see more. The depression gave poor angles on the reverse slope where Japanese reserves gathered. If the infantry attacked blind, those reserves would tear them apart.

The officer signaled: advance again.

The Second Position

To reach the next observation point, the team had to cross open ground exposed to at least three Japanese firing angles. While one man laid covering fire, the officer sprinted thirty yards uphill to the next patch of jagged rock.

Gonzalez followed ten seconds later, wire spool in hand.

A Nambu machine gun opened up. Tracers hissed over his shoulders. He kept running.

He stumbled once—caught himself—kept going.

The third Marine crawled forward under fire, dragging the second wire spool. A grenade exploded near him, knocking him flat. He rose anyway and finished the sprint, collapsing behind the rocks.

They spliced the wire, checked the line—still intact.

But Japanese infantry were beginning to move. Small squads filtered from cave entrances, shifting positions, preparing counterattacks. When artillery lifted again at 09:17, they began advancing.

The window was shrinking.

Only one position remained—one that would give perfect observation of both slopes.

It was also only eighty yards from the Japanese front line.

The officer pointed.

They would go.

Into Grenade Range

They left the depression at 09:19.

As they ran, trench rifles tracked them. Grenades arced toward them. Mortars walked rounds down the slope.

They reached the ravine—a deep volcanic cut that offered the best cover they had yet seen—and tumbled inside. Here, for the first time, they could see everything:

• a machine-gun bunker at 270°,

• mortar pits at 315°,

• a suspected command post at 155°, antenna faintly visible above stone,

• reserve troops assembling in a hollow behind the ridge.

It was a forward observer’s dream—and death sentence.

The officer set up his field phone. At Gonzalez’s direction, he began delivering target coordinates with calm precision.

Artillery struck with devastating accuracy. A mortar stockpile detonated in a chain of explosions. The machine-gun bunker collapsed. Ammunition caches blew apart.

The Japanese reacted immediately.

They began converging on the ravine.

At 09:43, grenades started landing close. The third Marine—bleeding heavily—held the entrance alone, firing steadily to keep the attackers back.

American artillery bought them precious minutes, shattering the first attacking wave. But the assault resumed as soon as the guns shifted.

The observers had one more task: destroy the forward Japanese trench line itself before the infantry assault at 13:00. But artillery could not strike so close unless the observers moved closer still, into the narrow strip of no man’s land between the opposing positions.

It was suicide.

But leaving the trenches intact would doom hundreds of Marines.

The officer nodded once.

They would advance again.

No Man’s Land

The third Marine could not continue. Blood loss made movement impossible. He would hold the ravine and keep the line open while the officer and Gonzalez pushed into the gap.

At 10:09, they climbed out.

The gap was seventy-eight yards wide—a jumbled mess of craters, shattered trees, and bodies. Every inch covered by Japanese fire.

They advanced in ten-yard rushes, hurling themselves into craters as bullets shattered the rocks around them. The wire spools paid out behind Gonzalez, the copper lifeline snaking through the blasted terrain.

At last, they reached a collapsed Japanese outpost—a crater deep enough to hide them, close enough to see directly into the Japanese trenches.

The officer connected the phone.

Gonzalez lifted his binoculars.

Targets filled his field of view.

Artillery struck the command post. Secondary explosions cracked across the ridge. Mortar positions vanished. Machine-gun nests blew apart. Japanese infantry scrambled for cover.

The defenders had no choice now. They rose from trenches and spider holes in coordinated counterattacks, determined to eliminate the observers who were dismantling their defenses one coordinate at a time.

They closed to seventy yards.

Then fifty.

Then thirty.

Grenades began landing inside the crater.

The Last Three Seconds

At 10:27, a Japanese soldier threw a grenade that landed three feet from Gonzalez, the officer, and the field phone that controlled half the division’s artillery.

The fuse sputtered.

There was no time to throw it back.

Not enough room to run.

No cover.

Only one calculation remained.

Gonzalez moved.

He threw himself onto the grenade, wrapping his arms over it as the blast erupted beneath him.

The explosion killed him instantly.

Shrapnel that would have killed two Marines and destroyed the field telephone tore through him instead. The officer survived with minor wounds.

He grabbed the handset and—through ringing ears—called the final set of coordinates.

Artillery struck the Japanese command post and forward trenches in rapid succession. Positions collapsed. Coordination evaporated. Colonel Udo’s forward headquarters ceased to exist.

Sixty seconds later, Japanese infantry overran the crater and shot the officer twice. He lived long enough to know the fire missions had gone through.

But the job was done.

Aftermath

At 13:00, Marines of the 4th Regiment attacked.

They met fierce resistance, but not the murderous crossfire that had awaited earlier assaults. The machine-gun nests were gone. The mortar pits were rubble. Ammunition dumps smoldered. Coordination among the defenders had shattered.

Mount Yayatake fell three days later.

The stronghold anchoring the northern Motobu Peninsula was broken.

PFC Harold Gonzalez did not live to see it.

His body was recovered the following morning. He was nineteen.

The officer survived his wounds and submitted a Medal of Honor recommendation detailing every moment of Gonzalez’s final act.

On June 19, 1946, President Harry Truman awarded Private First Class Harold G. Gonzalez the Medal of Honor for “conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity,” the only Hispanic Marine so honored in World War II.

But citations cannot capture the truth of those final three seconds on a volcanic slope in Okinawa—the moment when a nineteen-year-old forward observer made a calculation older than the Marine Corps itself:

My life, or their lives.

My choice, or no choice.

Move toward the grenade, or Marines die.

News

PIRATES OF THE ATLANTIC: The USS Buckley vs. U-66—A Shocking WWII Night Battle That Ended in the Last Boarding Action

U-66’s crew seized the moment. Wounded men vanished below. Fresh ones climbed out, gripping their flak guns. A silent oath…

GHOSTS IN THE SKY: The Devastating Mission Where Only One B-17 Flew Home From the Skies Over Germany

THE LAST FORTRESS: How One B-17 Returned Alone from Münster and Became a Legend of the “Bloody Hundredth”** On the…

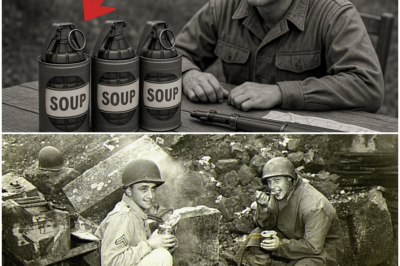

THE SOUP CAN CARNAGE: The Incredible, True Story of the U.S. Soldier Who Used Improvised Grenades to Kill 180 Troops in 72 Hours

THE SILENT WEAPON: How Three Days, One Soldier, and a Handful of Soup Cans Stopped an Entire Advance** War rarely…

DEATH TRAP IN THE SKY: The B-17 Pilot Who Flew One-Handed Through Fire With Live Bombs Inside to Save His Crew

THE PILOT WHO REFUSED TO LET HIS CREW DIE: The Extraordinary Story of 1st Lt. William Lawley and Cabin in…

UNMASKED: The Identity of the German Kamikaze Pilot Whose Final Tear Exposed the True Horror of Hitler’s Last Stand

THE LAST DIVE: The Sonderkommando Elbe, a Falling B-17, and a Miracle Landing On April 7th, 1945—just weeks before the…

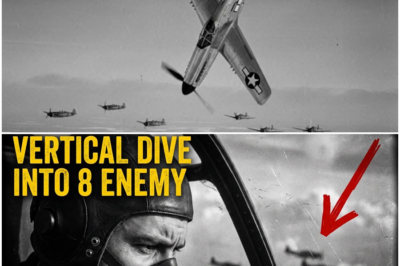

THE MUSTANG’S MADNESS: The P-51 Pilot Who Ignored the Mockery to Break Through 8 FW-190s Alone in a ‘Knight’s Charge’ Dive

THE DIVE: How One P-51 Pilot Rewrote Air Combat Over Germany The winter sky over Germany in late 1944 was…

End of content

No more pages to load