Eisenhower in Britain: The Inspections That Quietly Reshaped the Allied Path to Victory

When General Dwight D. Eisenhower first arrived in Britain in the summer of 1942, he did not yet resemble the confident Supreme Commander history now celebrates. Instead, he entered as a careful observer—an American newcomer stepping into a nation that had already endured nearly three years of unrelenting strain. What he encountered was a society weathered by bombing, stretched by shortages, and strengthened by survival.

Eisenhower came not to judge but to learn. And what he learned during those early months would quietly shape the strategic foundations of the entire Allied war effort.

A Nation Forged in Emergency

Britain in 1942 still bore visible reminders of the earlier crisis years. Streets carried the scars of air raids. Factories operated under blackout regulations. Rail networks worked under intense pressure, servicing both civilian needs and global wartime commitments. The British Army, though steadily rebuilding, still carried the imprint of earlier setbacks—from the collapse in France to the losses in Greece and North Africa.

Eisenhower traveled through coastal fortifications, airfields, armored training grounds, supply centers, and industrial regions. Everywhere he looked, he saw experience etched into people and equipment. Soldiers drilled with a discipline born from constant threat. Anti-aircraft crews reacted with the reflexes of veterans. Engineers kept vehicles and weapons in service through creativity, salvage, and repair.

But alongside resilience, Eisenhower detected strain. Equipment types varied widely. Mechanical reliability fluctuated across tank models. Small-arms production reflected years of improvisation rather than standardized mass manufacturing. Training practices differed between units, the result of learning under fire rather than developing doctrine through dedicated planning.

None of these conditions represented failure in Eisenhower’s eyes. They were the natural outcome of a nation that had stood alone during its darkest hour. Britain had fought with what it could build, repair, or adapt. It had chosen survival over efficiency—and survival had demanded sacrifices that shaped every part of its military system.

A Defense Built from Necessity Meets a Vision of Return

One of Eisenhower’s early realizations emerged while inspecting coastal defenses. These fortifications had been designed with one purpose: to repel invasion. Concrete bunkers faced the sea. Gun positions were oriented for defensive firing arcs. Logistic hubs were arranged for territorial protection rather than expeditionary movement.

This was entirely logical for a country that had survived the crisis of 1940. Yet it revealed a psychological orientation toward defense that no longer matched the strategic moment. Eisenhower’s mission differed fundamentally from Britain’s earlier struggle. The Allies would not win by merely preventing catastrophe—they would need to reconquer the continent.

He observed that even as British planners discussed future offensives, infrastructure, doctrine, and planning remained deeply influenced by the fear of renewed attack. Britain had fought a defensive war because it had to. Now, the Allies needed an offensive war because the stakes required nothing less. For Eisenhower, time had become the decisive factor. The longer the Allies remained structured around defense, the more entrenched German control of Europe became.

Divergent Military Cultures: Experience Meets Industrial Momentum

American and British forces brought fundamentally different wartime experiences to the partnership. British forces were shaped by years of loss, recovery, and adaptation. Their caution reflected bitter memories—Dunkirk, Crete, early desert defeats. For them, delay meant safety.

American forces arrived with new equipment, standardized systems, and a philosophy built on mass production and rapid movement. For them, delay meant danger.

Eisenhower stood at the intersection of these contrasting worldviews. He understood that the challenge ahead was not simply to combine armies, but to merge doctrines, logistical systems, and command structures. The goal was a single unified Allied instrument capable of fighting a large-scale continental campaign.

This required an unprecedented level of structural integration. And Eisenhower recognized that it would not happen on its own.

Logistics: The Quiet Battlefield Eisenhower Needed to Win

The more Eisenhower inspected, the more he saw that logistics—rather than tactics alone—would determine the future success of the war in Europe. British supply systems were extraordinarily efficient within their limits. They were built around conservation, rationing, and making the most of scarce resources.

Yet the liberation of Europe would demand something far beyond conservation. It would require volume, velocity, and sustained flow at levels never previously attempted in military history. Armies numbering in the hundreds of thousands would need continuous supplies of food, fuel, ammunition, vehicles, and spare parts.

Britain’s infrastructure had been built to endure attack. Eisenhower needed it to launch an offensive of unprecedented scale.

Thus began a quiet but profound transformation.

Ports were expanded to handle immense volumes of cargo.

Rail systems were upgraded to support heavy military transport.

Airfields multiplied across rural landscapes.

Storage depots grew beyond anything the pre-war planners had ever envisioned.

Fuel pipelines were laid in secrecy across vast regions.

These changes did not appear revolutionary in public announcements. But collectively, they reshaped the island into a logistical platform capable of supporting the coming return to Western Europe.

The Integration of Two War Machines

As American troops arrived in ever-increasing numbers, cultural contrasts became more pronounced. British officers brought invaluable battlefield knowledge. American officers brought fresh doctrine and industrial-scale thinking. Staff planning traditions differed sharply. Risk assessment differed even more.

Eisenhower understood that uncontrolled divergence could undermine the Allied cause. So he began introducing procedural changes that nudged the two systems into alignment:

planning staffs became integrated

command structures began merging

logistics forecasts used unified metrics

training programs increasingly operated under shared doctrine

By unifying assumptions, timelines, and operational metrics, he quietly rebuilt the Allied command environment from within.

What emerged over time was not a British system or an American one, but a hybrid structure capable of coordinating air, land, and sea power at a continental level.

Britain Transformed into a Launching Platform

By late 1943, Britain itself had changed beyond recognition. What Eisenhower had initially observed—a cautious fortress shaped by necessity—had evolved into the staging ground for the war’s decisive act.

Airfields expanded from grass strips into hardened bases.

Road networks carried ceaseless columns of vehicles.

Ports operated without pause, unloading cargo day and night.

Industrial zones produced equipment at the limits of their capacity.

Rural fields turned into training grounds, depots, and aircraft corridors.

The island had become a single, integrated war engine. It was an organism built not for survival but for projection—prepared to support the largest military operation in modern history.

A Fusion of Strengths

In the end, Eisenhower did not seek to replace the British system. He sought to expand it—preserving its strengths while reinforcing its limits with American abundance. British intelligence networks, radar systems, naval coordination, and disciplined command culture became the stabilizing backbone of a much larger structure.

American industry provided mass and momentum. British experience provided precision and resilience.

This combination produced an Allied force unlike any before it.

The Lasting Significance of Eisenhower’s Early Inspections

The importance of Eisenhower’s first months in Britain lies not in dramatic pronouncements but in quiet recognition. He saw that Britain’s system—remarkable for the war it had survived—was not yet optimized for the war still to come.

His response was not critique but architecture.

Not replacement but reinforcement.

Not confrontation but coordination.

The transformation he initiated turned an island recovering from crisis into the launch point of Europe’s liberation. It aligned two nations shaped by different wartime experiences into a single operational body. It created the infrastructure, doctrine, and logistics that would support the decisive campaigns of 1944 and beyond.

Eisenhower arrived in Britain as a student.

He left as the architect of Allied unity and the commander of a war machine built to overwhelm, not merely endure.

News

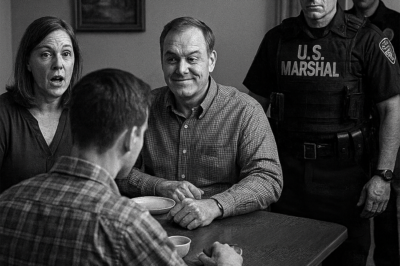

BETRAYAL AT TEA: We Sold Your House and Split the Money! — A Quiet Family Reunion Explodes as Parents Confess Shocking Act of Financial Treachery, Demanding the Unjustified ‘Contribution’

We sold your empty house and split money. Mom declared at tea the family reunion. You’re never even there. Dad…

The Unstoppable Rebuttal: Kid Rock Silences Critics Live on Air by Reading Every Word of Rep. Crockett’s “Dangerous” Demand, Freezing the Studio in Awe

The studio lights glowed softly as cameras prepared to roll, but no one in the room sensed the explosive moment…

CNN SHOCKWAVE: Senator Kennedy Unleashes Pete Buttigieg’s ‘Greatest Hits’ Resume Live on Air, Triggering a Terrifying 11-Second Silence That Tanked the Panel

The moment Jake Tapper leaned forward with that familiar smirk, viewers thought they were about to watch another predictable Washington…

You Can’t Serve Two Flags’: Crisis Hits Congress as 14 Lawmakers Instantly Ousted

The United States woke up today to a political firestorm unlike anything seen in modern history, as an explosive fictional…

‘State-Sponsored Kidnapping’: Senator Declares Total Legal War Over Secret School Policy

The uneasy political truce between Washington and Sacramento shattered violently this week when Senator John Kennedy stormed into the Senate…

The 5-Second Silence: Senator’s One-Line Challenge Leaves Two Leaders Speechless

Kennedy’s Confrontation With Jeffries and Harris Sparks Debate After Viral Capitol Hill Exchange A tense policy confrontation on Capitol Hill…

End of content

No more pages to load