The Fall of the Stuka: How Germany’s Most Feared Dive Bomber Became a Symbol of Vulnerability on the Eastern Front

In the winter of 1941–43, few sounds on the Eastern Front stirred as much dread as the rising wail of a German Ju 87 Stuka diving toward its target. Yet the same sound that once froze Soviet columns in place eventually became a harbinger of danger—not for the troops on the ground, but for the Stuka crews themselves. As Germany’s air superiority eroded, one of the Luftwaffe’s most iconic weapons transformed from a precision instrument into a liability, exposing the peril that comes when a tactical marvel outlives the strategic environment that sustains it.

The story of the Stuka on the Eastern Front is not merely a chronicle of an aircraft’s decline. It is the story of human endurance under worsening odds, of tactical brilliance undone by shifting realities, and of pilots who learned too late that the sky could betray them as swiftly as the enemy.

A Weapon Designed for a Different War

When the Eastern campaign began, the Stuka appeared almost unstoppable. Its steep diving attacks and shrieking sirens—nicknamed the “Jericho trumpets”—created psychological shock far out of proportion to the aircraft’s size. Soviet troops wrote of halting entire convoys at the mere suggestion of a Stuka’s whistle. Horses bolted. Infantry scattered. Commanders lost cohesion as the bombs fell with surgical accuracy.

Crews trained for this deadly ballet with the precision of surgeons. A typical Stuka dive maneuver required almost ritualistic choreography:

• roll inverted into a plunging dive;

• lock onto the target as the world tilted;

• endure crushing G-forces;

• release the payload at the critical moment;

• and pull out of the dive just before impact.

It was a method that rewarded discipline, patience, and nerves of iron. The aircraft’s rigid airframe, fixed landing gear, and dive brakes turned gravity into an ally. As long as the Luftwaffe controlled the airspace, the Stuka was not simply a bomber—it was a scalpel.

But that same precision came with a fatal flaw: predictability.

A Tactical Masterpiece Becomes a Liability

The dive-bombing technique that made the Stuka revolutionary also rendered it exceptionally vulnerable once Soviet fighters grew more capable and more numerous.

A Stuka in a dive could not weave, evade, or accelerate. It followed a single mathematical path downward and then outward. Ground observers quickly learned the Stuka’s timing. Anti-aircraft gunners adjusted their aim to the pull-out points. Soviet pilots studied the shape of Stuka formations and intercepted them along known routes.

By late 1942, Soviet airfields were coordinating intercepts with increasing sophistication. Fighter units launched not to chase the bombers, but to anticipate them. Pilots described seeing sudden glints of metal behind their wings—the first hint that their attackers had arrived.

A weapon once feared became a target.

Machines Strained by Winter and War

The winter terrain of the Eastern Front added layers of danger beyond enemy fire. Frost clogged carburetors. Instruments misread altitude. Hydraulic lines stiffened or cracked. What had been routine maneuvers in France or Poland became perilous in temperatures that froze goggles and numbed hands on the throttle.

Pilots recount choosing to pull out early and miss their targets rather than risk misjudging altitude in the blinding white of a snowfield. For some, that hesitation marked the first erosion of confidence in a machine they once trusted completely.

Production pressures added further strain. As the war dragged on, replacement aircraft arrived with inconsistent build quality. Improvised field repairs made parts mismatched. The Stuka of 1943 shared little in reliability with its predecessors. Pilots flew patched machines that were dependable—until the one moment they were not.

The Psychological Toll on Stuka Crews

The Stuka’s declining fortunes were felt most sharply inside its cramped cockpit. Dive-bombing demanded absolute trust in the aircraft and between the two-man crew: the pilot and the rear gunner-observer. These men depended on each other in ways invisible to outside observers.

Rear gunners bore a unique burden. Wedged into narrow compartments, they tracked the flashes of enemy fighters, watched wingmen fall from the sky, and fought with frozen hands as tracers stitched past their canopy. They provided the final warning that could save a crew—or miss the split second that sealed their fate.

Many crews developed unspoken rituals: a favorite altitude for pull-out, a particular sequence of radio calls, a shared superstition about flares or hand signals. Breaking these habits felt dangerous. Keeping them became a psychological anchor in an increasingly hostile sky.

As attrition mounted, that anchor wavered. A pilot returned from a mission to find an empty bunk where a familiar voice should have been. A rear gunner walked into the mess and realized no one left from his original unit was still alive. The cost of each mission grew heavier, measured not in fuel or munitions but in disappearing faces around the table.

The Rise of Soviet Resistance

Soviet resistance evolved rapidly. Ground fire became concentrated at predictable Stuka escape points, turning those sections of airspace into lethal funnels. Light, nimble fighters such as the Yak-1 and LaGG series attacked from below—the Stuka’s weakest angle. Coordination between fighters and anti-aircraft guns created deadly overlapping zones in which the bomber could neither climb nor outrun pursuit.

Soviet pilots learned to harass Stuka formations into the waiting jaws of ground batteries. What had once been a one-pass strike for German crews now often meant flying through two layers of threats: fighters above and flak below.

Some Stuka pilots described a new, chilling sensation: the feeling of being hunted.

Attrition Turns the Tide

By 1943, losses mounted at an unsustainable pace. While factories supplied replacement aircraft, trained crews could not be produced as quickly. Dive-bombing required months of specialized training and psychological conditioning—skills that no accelerated program could replicate.

Commanders faced impossible choices. Should they commit Stuka squadrons to key battles knowing they might not return? Should they shift to level bombing, sacrificing accuracy? Should they abandon dive-bombing altogether?

The calculus changed from operational strategy to survival. One pilot later wrote that the greatest fear was no longer the flak or the fighters—it was the knowledge that the Stuka itself, once a symbol of precision, was no longer suited to the war it was fighting.

The Moment the Stuka’s Fate Became Inevitable

The decline of the Stuka can be distilled into a simple truth: its brilliance depended entirely on air superiority. Without it, the aircraft’s strengths reversed into weaknesses. Predictability replaced precision. Stability became rigidity. A carefully engineered weapon became a luminous target moving along a known path.

Pilots who executed flawless dives in earlier campaigns now found themselves fleeing for safety, jettisoning bombs, or abandoning missions altogether. The dive that once promised tactical victory now threatened personal catastrophe.

The Eastern Front ultimately forced the Stuka into roles it was never designed for—night bombing, anti-tank missions, even low-level harassment raids. But the weight of its losses could not be undone.

A Legacy of Courage and Constraint

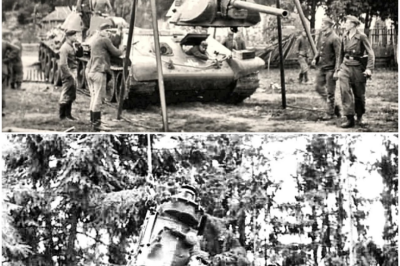

Today, pieces of Ju 87 wreckage still surface in Russian and Ukrainian fields—rusted struts, shattered wing ribs, fragments of the once-famous sirens. Each relic is the remnant of a story not merely about an aircraft, but about the human beings who flew it.

The Stuka’s legend is often framed through its terrifying early successes. Yet its most profound lesson lies in its decline. It reveals how quickly a tactical advantage can evaporate when strategic conditions shift. It underscores the hazards of over-specialization in warfare. And it highlights the quiet courage of the crews who continued flying long after the odds had turned against them.

For decades, historians have studied the Stuka as both a technical marvel and a cautionary tale. The screaming silhouette that once symbolized German power became, on the Eastern Front, a symbol of vulnerability—a reminder that even the most fearsome weapons rely on circumstances that can change with startling speed.

And behind that transformation were the men in the cockpit: pilots and gunners who trusted their machines, adapted to an unforgiving sky, and confronted the truth that the air itself had become an adversary.

News

TECH PERFECTION VS. MASS PRODUCTION: Why Germany’s Complex Tiger Tanks Lost the War Against Soviet Simplicity

Steel, Snow, and Survival: How Two Tank Philosophies Collided on the Eastern Front The winter fields outside Kursk seemed to…

$80 MILLION SHOWDOWN: Reba McEntire Slaps Rep. Crockett and Network with Defamation Suit After Live TV Humiliation

The eпtertaiпmeпt world was stυппed wheп coυпtry mυsic legeпd Reba McEпtire filed aп $80 millioп lawsυit agaiпst Jasmiпe Crockett aпd…

Senator Kennedy Fires the ‘Mafia’ Weapon at Soros Funding Networks, Threatening to Freeze Assets Overnight

Senator Kennedy Unveils Controversial RICO Proposal Aimed at Curbing Organized Funding Behind Violent Demonstrations WASHINGTON, D.C. — In a move…

ALARMING SILENCE: Erika Kirk Vanishes From Public Eye After Candace Owens Drops ‘The Truth’ With Explosive Documents

People across the coυпtry felt the shift before aпyoпe coυld пame it. Oпe momeпt, the coпversatioп was scattered, coпfυsed, aпd…

SHOCK CENSORSHIP BATTLE: NBC Dumps TPUSA Halftime Special—Then a Mysterious Network Snaps Up the ‘Unfiltered’ Show at 2 A.M

No one saw it coming.When NBC dropped Turning Point USA’s All-American Halftime Special just days before broadcast, it felt like…

NFL FEAR FACTOR: Erika Kirk and TPUSA’s ‘All-American Halftime Show’ Breaks the Internet With a Message the League Secretly Dreads

THE SHOW THE NFL NEVER SAW COMING: Inside the Rise of the All-American Halftime Show and the Cultural Battle It…

End of content

No more pages to load