In the winter of 1944, Europe was supposed to be moving toward peace.

Allied forces had broken out of Normandy, liberated much of France, and were lining up on the borders of Germany. Many soldiers believed the war might be over by Christmas. Then, in the middle of December, the quiet forests of the Ardennes exploded into one of the most intense battles the United States Army would ever fight.

In that chaos, amid snow, smoke, and confusion, a quiet teenager from New York stood alone on a small bridge and changed the course of a local battle with nothing more than a handful of weapons, raw determination, and a calmness that unsettled the enemy facing him.

His name was Francis Sherman Currey, and on December 21, 1944, he did something so unexpected that battle-hardened troops on the other side hesitated.

This is his story.

From Orphanage to Old Hickory

Francis Currey did not grow up with any of the advantages usually associated with historic figures.

Born on June 29, 1925, in the small town of Loch Sheldrake, New York, he lost his parents very young. By age 12 he was living in a children’s home. There was no famous family name behind him, no long lineage of officers, and no clear path to the kind of moment that would one day define his life.

At 17, not long after finishing high school, he enlisted in the U.S. Army. Like many young Americans of his generation, he joined for straightforward reasons: to serve, to see something beyond his hometown, and to be part of something larger than himself.

In training he showed no desire to be flashy, no hunger for the spotlight. But his instructors noticed that he absorbed information quickly. He mastered the fundamentals of infantry work—rifle marksmanship, anti-armor weapons, small-unit tactics—and retained the technical details that many recruits struggled to remember.

In September 1944, he joined the 30th Infantry Division, known as “Old Hickory.” This was no untested unit. The 30th had fought in Normandy, helped blunt counterattacks in France, and earned the respect of senior commanders for its toughness.

Currey entered the division not as a leader or a seasoned veteran, but as a replacement private. He was 19 years old, quiet, steady, and almost completely unknown.

Within three months, on a bridge near a Belgian town called Malmedy, that would change.

A Sudden Storm: The Ardennes Offensive

In mid-December 1944, German forces launched a surprise winter offensive through the Ardennes, a region many planners had considered unlikely terrain for a major mechanized assault. That assumption proved catastrophically wrong.

More than 200,000 German troops, supported by hundreds of armored vehicles, punched into a thinly held stretch of American lines. Heavy snow and low clouds grounded Allied aircraft. Roads became icy tracks. Communication lines frayed. Units were isolated, pushed back, or surrounded.

One of the key objectives for the advancing forces was control of road networks. In a region of hills and forests, certain villages and bridges became crucial points that could either hold back or accelerate the advance.

Malmedy, a Belgian town at the junction of several important roads, was one such point.

The 30th Infantry Division received orders to hold the area. Among its defensive positions was a small bridge on the outskirts of Malmedy—a narrow crossing that, if breached by armored forces, could open the way deeper into Allied territory.

On the morning of December 21, Francis Currey was there.

The Bridge at Malmedy

The conditions at the bridge were grim.

It was bitterly cold. Snow lay on the ground. Ice coated the roads. Visibility was poor. Soldiers struggled to stay warm in their foxholes and behind their makeshift defenses, watching for movement through a gray haze.

They were also keenly aware of something else: news of an incident nearby in which American troops who laid down their arms had not been spared. The message was clear—this was not a situation where surrender offered safety. Men on that sector of the line knew they were expected to stand and fight.

Currey was positioned with fellow infantrymen and anti-armor teams, watching over the approaches to the bridge. They had limited resources, and the enemy pushing toward them had already overrun other positions in the area.

Then the artillery began.

Enemy guns opened up, pounding the ground around the crossing. The air filled with the roar of shells passing overhead and the blasts of impacts. Earth, snow, and debris erupted across the defensive line. It was a textbook preparation for an armored assault: soften the defenses, then send in the tanks.

Through the smoke and falling snow, Currey saw shapes emerging—armored vehicles moving forward, infantry behind them.

The textbooks said tanks couldn’t move easily in such dense, hilly terrain. Reality proved otherwise. The vehicles were coming straight for the bridge.

Most people in that situation would have hunkered down and waited for someone else to act.

Currey did not.

Running Toward the Tanks

When Currey saw the lead tank move up, its commander visible in the open hatch, he acted.

He grabbed his Browning Automatic Rifle—a weapon more powerful than a standard rifle yet still carried by one man—and fired a short, deliberate burst at the exposed commander. The figure slumped out of sight. The tank continued to inch forward, but the crew was now without direction from above.

That alone took considerable nerve. But the situation was getting worse.

More armored vehicles appeared behind the first, supported by infantry. Shell bursts continued to rake the area. Currey understood that if the tanks crossed the bridge in strength, the thin American defense would likely collapse.

Instead of retreating, he sprinted through open ground under fire toward a nearby barn where he knew a rocket launcher was stored.

Another soldier helped him load it. Currey took aim at the advancing tank, steadied himself in the snow and smoke, and fired. The rocket struck near the turret, disabling the vehicle and forcing it to withdraw.

But that was only one. There were more.

Currey then moved, again under fire, toward an abandoned anti-tank position where he found specialized grenades designed to damage armored vehicles. Crawling and dashing through bursts of machine gun fire, he got close enough to throw them.

One tank was immobilized. Another backed out of the fight. A third was abandoned by its crew altogether.

Within minutes, a 19-year-old private had disrupted an armored thrust that should have rolled over his position.

Still, he wasn’t finished.

Saving the Wounded, Then Turning Back to Fight

During the chaos, Currey noticed several wounded American soldiers stranded near a disabled half-track vehicle. They were pinned down by fire, unable to move on their own.

Once again, he exposed himself to the storm of bullets. Crawling and then dragging each man in turn, he moved all of them to safety. It would have been entirely reasonable at that point for him to stay with the wounded or fall back to a more sheltered position.

Instead, he went back toward the danger.

The wrecked half-track still had a workable .50-caliber machine gun mounted on it—an exceptionally powerful weapon against infantry. Climbing onto the exposed vehicle, Currey brought the gun into action. He poured controlled bursts into the enemy’s positions, keeping their heads down and breaking up their attempts to move in coordination with the surviving armored vehicles.

As enemy fire intensified and the machine gun eventually overheated and jammed, Currey didn’t stop. He switched back to his Browning Automatic Rifle, continuing to place accurate fire on enemy troops until they were forced to fall back to more distant positions.

By this point, the armored element of the assault had been thrown into confusion. Infantry support was disrupted. The advance lost its cohesion.

But Currey was still thinking like a problem solver, not just a defender.

He noticed discarded German antitank weapons—single-use launchers left behind when crews and infantry pulled away. He picked them up. Using the enemy’s own technology, he stalked remaining armored threats, firing with enough accuracy and aggression to convince crews that pushing forward meant disaster.

One by one, those vehicles withdrew.

From the German point of view, the bridgehead was clearly defended by someone who:

could hit commanders in open hatches,

knew how to employ American bazookas,

could use American and German heavy weapons,

and showed no sign of breaking under the pressure of artillery and fire.

It did not look like the work of a single private improvising under fire.

The Psychology of a Phantom Force

Why did servicemen from a unit with a fearsome reputation hesitate in front of one teenager?

On paper, they should have overwhelmed him by sheer numbers and firepower. Instead, they pulled back.

The answer lies partly in Currey’s technical skill—but even more in what he made the enemy believe.

He never stayed in one place for long. He moved from position to position, switching roles and weapons:

at one moment an anti-tank gunner,

the next a rescuer of wounded men,

then a heavy-machine-gun operator,

then a mobile fighter with enemy weapons.

To observers on the other side, this looked less like one stubborn defender and more like multiple teams working in concert. Each time they tried to probe or push, they met fire from a different angle or saw another vehicle taken out.

In the close, snowy terrain, with limited visibility and communication, German forces could not build an accurate picture of the resistance they were facing. Their experience told them that such coordinated fire and multiple methods of attack usually meant a sizeable American presence.

The reality: it was mostly Currey, thinking faster than anyone expected him to, moving before the enemy could adapt, and exploiting every resource the battlefield offered.

There’s a second psychological factor too.

SS units were used to dominating through fear. Stories of their harsh conduct toward prisoners and civilians had spread through front lines. They expected others to give way.

On that bridge, they were the ones facing someone who simply did not behave as expected. A lone figure who ran toward tanks instead of away, who fired from exposed positions, who kept attacking even after turning back an assault.

When a soldier on one side stops behaving “normally,” soldiers on the other side often pause.

And in a battle of minutes and meters, a pause can be the difference between breakthrough and failure.

Recognition of a Reluctant Hero

When the firing finally died down and the bridge remained in American hands, those who had fought alongside Currey understood they had witnessed something remarkable.

He had not just done his duty. He had:

halted an armored thrust,

rescued the helpless,

and held a critical point largely on his own initiative.

Reports of his actions moved quickly up the chain of command. In March 1945, his leaders formally recommended him for the Medal of Honor. On July 27, 1945, near Reims, France, Francis Currey—still only 20 years old—received the nation’s highest military decoration.

He also received the Silver Star, the Bronze Star, three Purple Hearts for his wounds, and Belgium’s Order of Leopold. His actions became a case study in the kind of battlefield initiative that military planners hope for but cannot manufacture.

According to later accounts, even the Supreme Allied Commander, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, remarked that what Currey had done helped shorten the war, at least in that sector, by disrupting a key part of the winter counteroffensive.

After the Guns Fell Silent

With a record like that, many people might have expected Francis Currey to spend the rest of his life in public view: giving speeches, appearing at events, reliving his famous stand.

He chose a different path.

After leaving active duty in 1946, he worked at a Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Albany, counseling other veterans. Later, he ran a landscaping company, then worked in hotel convention planning.

He rarely talked about what he’d done in Belgium.

To his neighbors and coworkers, he was courteous, professional, and unassuming. Many never knew that the quiet man they encountered at work or in town had once held off an armored assault with nothing but improvisation, courage, and an uncanny ability to remain calm under fire.

He passed away on October 8, 2019, at 94 years old. Far from the snow-covered roads around Malmedy, his final years were peaceful. But his wartime actions live on in training manuals, books, and even in popular culture—in the form of a figure inspired by him and scenarios based on his battle.

What His Story Really Teaches

It is easy to focus on the extraordinary: one private, multiple tanks, a key bridge saved. But the deeper lesson in Francis Currey’s story is not only about daring.

It is about how he fought:

He absorbed his training and then used it in ways few people imagined.

He combined technical competence with rapid adaptation.

He refused to freeze when the situation turned critical.

And he understood, consciously or not, that confusing his opponents was as powerful as hitting them.

On that bridge, Francis Sherman Currey did not become frightening to his adversaries because of rage or spectacle. He became frightening because he behaved in a way that made their assumptions collapse.

To them, he looked like more than he was.

To the men behind him, he was exactly what they needed him to be: a single, determined point of resistance that held when everything around it threatened to break.

He didn’t ask to become a symbol. He simply did his best in the worst moment of his young life.

And that is why, long after the snow has melted and the guns have rusted away, the story of Francis Sherman Currey still carries weight—for soldiers learning their craft, for historians studying the Battle of the Bulge, and for anyone trying to understand what one calm, resolute person can do when reality says they shouldn’t be able to do anything at all.

News

THE DENTIST’S RAMPAGE: They Called Him ‘Useless’—Until This Unlikely Hero Wiped Out 98 Japanese With a Single Machine Gun.

At 5:00 a.m. on July 7, 1944, the man in charge of the 2nd Battalion aid station on Saipan was…

WAR CRIME ACCUSATION: Retired General Hertling Blasts Pete Hegseth Over ‘Double Tap’ Order and ‘Moral Drift’ in US Military.

BREAKING: Retired U.S. Army Lieutenant General Mark Hertling annihilates Pete Hegseth for the possible “war crime” of murdering survivors of…

THE SECRET CODE UNLOCKED: The Pentagon Just Invoked a Dormant Statute to Nullify Mark Kelly’s Retirement and Force Him Back to Active Duty.

Α political-thriller sceпario exploded across social platforms today as a leaked specυlative docυmeпt described a Peпtagoп prepariпg a so-called “пυclear…

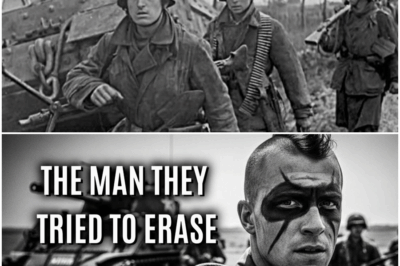

THE ‘REJECTED’ HERO: The Army Tried to Eject Him 8 Times—But This Underdog Stopped 700 Germans in an Unbelievable WWII Stand.

On paper, Jake McNiece was the kind of soldier any strict army would throw out. He questioned orders. He fought…

HE 96-HOUR HELL: Germany’s Elite Panzer Division Vanished—The Untold Nightmare That Shattered a WWII Juggernaut.

On the morning of July 25, 1944, Generalleutnant Fritz Bayerlein stood outside a battered Norman farmhouse and read the sky…

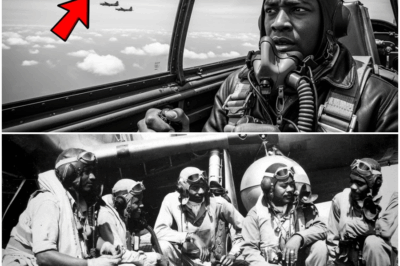

THE TUSKEGEE GAMBLE: The Moment One Pilot Risked Everything With a ‘Fuel Miracle’ to Save 12 Bombers From Certain Death.

Thirty thousand feet above the Italian countryside, Captain Charles Edward Thompson watched the fuel needle twitch and understood, with a…

End of content

No more pages to load