On paper, Jake McNiece was the kind of soldier any strict army would throw out.

He questioned orders. He fought military police. He ignored regulations that everyone else treated as sacred. His personnel file was a stack of disciplinary reports thick enough to choke a filing cabinet.

And yet, when some of the most critical moments of the Second World War arrived—Normandy, a shattered bridge in France, the frozen siege of Bastogne—Jake and the small knot of men around him were exactly where the United States needed them most.

The same army that tried to get rid of him eight times kept calling on him when the odds were worst.

This is the paradox of Jake McNiece: a man who never fit the uniform, but wore it better in combat than almost anyone else.

Building a Misfit’s Platoon

Jake grew up in rural Oklahoma during the Great Depression, one of ten children in a family that survived by working the land and taking every opportunity they could find. He learned to shoot as soon as he could hold a rifle. Hunting wasn’t a sport; it was how meat ended up on the table.

By the time most boys were still in school, Jake was working as a firefighter. Running into burning buildings while others ran out became his normal. It tuned him to a simple logic: if something needs doing, you do it. You don’t wait for permission.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, he volunteered for the paratroopers. Not for ceremony or speeches, but because jumping behind enemy lines with explosives sounded like the most direct route to the job he wanted: breaking the enemy’s ability to fight.

The army assigned him to Fort Benning for training. Almost immediately, he collided with military culture.

In the mess hall one morning, a staff sergeant took his butter ration and told him to sit down and be quiet. Jake warned him once. When the sergeant laughed, Jake broke his nose. It was the kind of incident that usually ended with a courtroom and a dishonorable discharge.

That same day, on the demolition course, Jake set a base record for speed and accuracy.

This pattern repeated. Every time he caused trouble, he also did something the instructors couldn’t ignore: outshooting their best marksmen, outrunning their strongest runners, enduring more weight on longer marches than anyone else.

He refused to call officers “sir” unless he respected them. He skipped formations he thought were pointless. When a lieutenant demanded to know why he couldn’t behave like a “proper soldier,” Jake answered with a line that would echo across the base: “I’m here to fight the enemy, not shine boots.”

The higher-ups were torn. On one hand, he was a discipline problem. On the other, he was exactly the kind of fighter they knew they would need.

Their solution was, unintentionally, to create something unique.

Instead of throwing him out, they gave him his own platoon, his own barracks, his own little corner of the 101st Airborne. When other units produced men who were too wild to handle but too capable to waste—brawlers, outsiders, rule-breakers with talent—those men were quietly reassigned to Jake.

In a matter of months, he had collected a dozen such misfits. A coal miner who had knocked down three military policemen in a single bar fight. A multilingual former smuggler whose talent for reading people made him a natural interrogator. A demolitions enthusiast who once used explosives to “study blast patterns” on a latrine. A street fighter with a boxing record that made even instructors hesitant to spar with him.

To everyone else, these men were problems. To Jake, they were raw material.

They became known as the “Filthy 13”—partly for their appearance, partly for their contempt for spit-and-polish discipline. They trained harder than anyone. They ran farther. They shot more. They practiced fieldcraft until moving silently and surviving on almost nothing became second nature.

Jake didn’t enforce discipline the way most officers did. There were no lectures about posture. Instead, he had a single standard: be extremely good at your job, or go somewhere else.

The army disapproved of almost everything about how he ran his platoon. But they could not ignore the outcome: in every meaningful military test—marksmanship, endurance, hand-to-hand training—Jake’s misfits came out on top.

Normandy: Falling From Fire into Water

In early June 1944, as Allied forces prepared to invade Normandy, Jake added another layer to his legend.

He shaved his hair into a mohawk and painted white stripes across his face. It was not a stunt, at least not in his mind. It was a ritual. Once he stepped out of the aircraft, he wanted to feel that he had crossed a line into another self—one focused purely on survival and mission.

His men followed suit with their own variations. A military photographer from the armed forces newspaper happened to see them and took several photos. Those images—bare-chested paratroopers with mohawks and war paint—would become some of the most iconic pictures of airborne troops in the war.

On the night of 5 June, Jake and his platoon boarded a C-47 transport aircraft bound for France. The plan was to jump into Normandy ahead of the main invasion, seize and hold key routes, and prevent German reinforcements from reaching the beaches.

The flight was tense but uneventful until they reached the French coast after midnight.

Then the sky lit up.

German anti-aircraft guns opened fire, filling the air with bursts of fire and steel fragments. The aircraft bucked under the impacts. Inside, the jumpmaster yelled for the men to hook up their static lines.

Three minutes later, an anti-aircraft shell hit the plane’s fuel tank. The explosion tore through the fuselage. Fire and shrapnel ripped into the troop compartment. The rear of the aircraft began to disintegrate.

Jake was standing in the door when the blast blew him into the open air.

He didn’t feel the wind at first, only heat and impact. His parachute deployed automatically, but it was damaged—partially burned, partially shredded. He dropped fast toward a flooded marsh.

Hitting water under canopy can be as dangerous as hitting ground. The harness tangled around his legs, dragging him under. Many paratroopers drowned that night in similar situations.

Jake used his knife.

Calmly, he cut himself free, pushed through the cold water, and surfaced amid floating debris from the exploding aircraft.

The countryside around him was chaos: burning wreckage, stray gunfire, distant shouting. He swam, crawled, and stumbled through hedgerows and ditches until he began to find others—men from his own platoon and from scattered units.

By dawn, he had gathered nine survivors from the Filthy 13. Four were missing—presumed dead or captured. They were behind enemy lines, with no clear map, no radio, and no resupply.

Their orders had been to capture and hold a bridge near a village called Chef-du-Pont to block German movements. The intelligence estimate said hundreds of German troops guarded the area.

Jake didn’t consider those numbers decisive. He had men, weapons, and a mission.

They moved.

The Bridge and the Hill

Using terrain and surprise, Jake’s group ambushed small German patrols, hit hard, and disappeared before organized counterattacks could form. As they advanced, they picked up scattered American paratroopers from other units. Nine men became fifteen. Then twenty. Eventually thirty-five.

By late morning on 6 June, this small, improvised force seized the bridge at Chef-du-Pont.

It was an important tactical achievement. Holding that crossing restricted German ability to move west toward the beaches. For a few hours, the mission looked like a complete success.

Then American fighter-bombers appeared.

Acting on orders issued before the airborne drops—orders that assumed the bridge would be in German hands—P-47 pilots attacked the structure. Jake’s men tried desperately to signal that they were friendly, but smoke and confusion obscured everything.

The bridge was destroyed by American bombs.

The objective Jake’s men had fought to secure no longer existed. They were stranded on the far side of a destroyed crossing with no way back, deep in contested territory.

For many units, this would have been the moment to try to slip away and reconnect with larger formations. Jake took a different view. There was still high ground overlooking the crossing, and high ground is always valuable.

He studied the hill above the ruined bridge and saw what others might not: narrow approaches, natural choke points, angles that would favor defenders.

He turned it into a fortress.

He placed his machine guns where their fields of fire overlapped. He stationed riflemen with clear views of likely approach routes and told them to target leaders—officers and noncommissioned officers—to collapse German command and control. He kept a small reserve on hand to plug any break in the line.

The men were exhausted, hungry, and dehydrated. They had been fighting, moving, and evading for nearly two days without proper rest or supplies. But their positions were sound.

On the German side, reports indicated that roughly 700 troops of varying units were assembling for an assault on the hill.

“If You Want It, Come Take It”

On the morning of 9 June, as German forces prepared to attack, an officer approached the American positions under a white flag.

He came not to surrender, but to offer terms.

From his perspective, the situation was obvious. Thirty-odd paratroopers, cut off and unsupplied, facing repeated assaults by a force twenty times their size. He pointed out that he had heavy weapons, food, water, and more men ready. The Americans, in his view, had courage and nothing else.

Logic, from the German vantage point, dictated surrender.

Jake listened. Not because he was considering it, but because he understood respect for a formal gesture, even between enemies.

After the officer finished his argument, Jake gestured back at the slope.

“If you want this hill,” he said, “start climbing.”

The German walked back down. The white flag went away. The attacks began.

Wave after wave came up the hill—infantry in formations, then with mortar support, then with tanks and artillery. Each time, the ground forced them into narrow channels where Jake’s machine guns and rifles could reap maximum effect.

He instructed his men not to fire too early. Let the attackers get close. Let them bunch up. Then concentrate fire where it would cause the most chaos.

German mortars pounded the crest. Jake had wisely put many of his positions just behind it on the reverse slope, where shell fragments were less lethal. Tanks rolled forward along the road, their guns unable to elevate enough to hit his hidden positions while his men focused on the infantry they sheltered.

By the end of several attacks, more than a hundred German soldiers were dead or incapacitated. Many more were wounded. Jake’s men recorded no casualties in their own ranks.

The numbers seemed nearly impossible. But they were the combined result of terrain, skill, discipline of a very particular kind, and a willingness to stand in place long after a more conventional unit might have broken.

Another Kind of War

Jake’s combat record could have easily ended in 1944 and still marked him as an extraordinary soldier. But his war did not end with Normandy.

Six months later, another crisis called him.

In December 1944, when German forces launched a surprise offensive in the Ardennes, the town of Bastogne became the focal point of the fight. Surrounded, undersupplied, and under nearly constant attack, the American defenders needed food, ammunition, and medical supplies desperately.

The only realistic way to get those supplies into a ringed city under poor weather was by air. And the only way to make those drops precise enough to matter in fog and snow was to send in pathfinders—specialist paratroopers to jump into the cauldron, set up radio beacons, and guide the planes in.

It was a mission commanders described, even privately, as near-suicidal.

Jake volunteered.

He and a handful of other pathfinders jumped into Bastogne through clouds and flak, landed amid chaos, dodged shells, and located each other in a town on the edge of being destroyed. Working with local units, they set up and operated beacons in shifting locations under constant threat.

Over roughly twenty-four hours, they guided in hundreds of supply drops. Without those supplies—ammunition, food, medical kits, winter clothing—the exhausted defenders could not have held out until ground relief arrived.

Most people in America never learned the names of those pathfinders. The operation was classified. In the public mind, the narrative of Bastogne fixated on the famous “Nuts” reply to a German surrender demand and on the dramatic arrival of armored units.

Somewhere beneath that story, men like Jake worked in freezing conditions with barely any rest, making sure that the boxes falling from the sky landed among allies instead of enemies.

Quiet Years, Quiet End

When peace finally came, the army did not quite know what to do with Jake.

He had served in some of the fiercest battles of the European war. He had saved more men than anyone could count. He had also broken more regulations than could neatly fit into an average service file. He never rose above the lowest enlisted rank, despite his achievements, because his disciplinary record was as long as his combat record.

Eventually, after another clash with military police during occupation duty, the army did something that probably relieved both sides. It discharged him honorably.

Jake went home to Oklahoma.

The transition to civilian life was not easy. Like many combat veterans, he carried the war inside him long after it ended. He drank heavily for a time, struggled with anger and restless energy, and crashed hard—literally, in a car accident that made him confront the fact he had survived too much to waste the life he had left.

He stopped drinking. He married. He took a job at the post office, raising children, sorting mail, and attending church.

He didn’t fill his home with war memorabilia. He didn’t brag in bars. He didn’t replay his battles at the dinner table. To most who met him in those later years, he was simply the polite man who sold stamps and cheered from the sidelines at local games.

He died in 2013 at the age of 93. Only then, as old photographs and unit histories resurfaced, did many people realize that the quiet postal worker had once told a German officer, “If you want this hill, come take it,” and meant it.

The Measure of a Man the System Couldn’t Rate

It is tempting to view Jake McNiece as an exception, a wild card who somehow slipped through the cracks of a system designed for order. There is some truth to that.

But his story also reveals something important about that system: when it mattered most, the army did not just tolerate him—it needed him.

The rigid structures of military life can produce discipline. They can also stifle initiative if enforced without thought. Jake’s refusal to obey meaningless rules, combined with his absolute dedication to what he saw as the real mission—protecting his men and defeating the enemy—made him a problem in barracks and an asset in combat.

He refused to separate discipline from purpose.

When he built the Filthy 13, he wasn’t undermining the army. He was, in his own rough way, sharpening it. He took men the institution didn’t know how to use and forged them into a team that could thrive in the kind of chaos no training manual had fully predicted.

That is why, at a destroyed bridge in France, thirty-five of his men held off hundreds. Why, in the frozen fog of Bastogne, his signals kept planes flying. Why, decades later, men who never knew his name nonetheless lived in a world shaped by the battles he fought.

The army tried to throw him away. War would not let it.

News

HE 96-HOUR HELL: Germany’s Elite Panzer Division Vanished—The Untold Nightmare That Shattered a WWII Juggernaut.

On the morning of July 25, 1944, Generalleutnant Fritz Bayerlein stood outside a battered Norman farmhouse and read the sky…

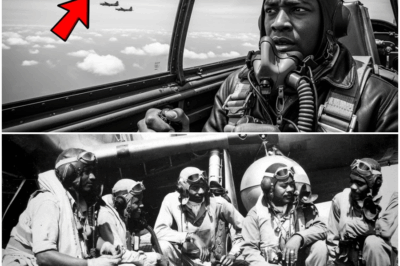

THE TUSKEGEE GAMBLE: The Moment One Pilot Risked Everything With a ‘Fuel Miracle’ to Save 12 Bombers From Certain Death.

Thirty thousand feet above the Italian countryside, Captain Charles Edward Thompson watched the fuel needle twitch and understood, with a…

THE ‘STUPID’ WEAPON THAT WON: They Mocked His Slingshot as a Joke—But It Delivered the Stunning Blow That Silenced a German Machine-Gun Nest.

In the quiet chaos of Normandy’s hedgerow country, where every field was a trap and every hedge could hide a…

THE HIDDEN MESSAGE IN A MARINE’S PORTRAIT: It Looked Like a Standard Family Photo, But One Tiny Detail in Their Hands Hides a Staggering Secret.

In a small studio at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, a photographer captured what looked, at first glance, like a routine…

This Farm Boy Fixed a Jammed Machine-Gun — And Changed the Battle

On a foggy French hillside in the early hours of September 13, 1944, a 19-year-old farm boy from Iowa found…

They Gave a Black Private a “Defective” Scope — Until He Out-Sniped the German Elite in One Hour

On a cold October morning in 1944, the fog over the Moselle Valley hid more than just treelines and concrete…

End of content

No more pages to load