Lieutenant General George S. Patton Jr. walked into the Ardennes crisis with a reputation that was already larger than life. What he did there turned that reputation into something else entirely: proof that one man’s preparation, instinct, and audacity could change the course of a campaign that had begun as a catastrophe.

In December 1944, Hitler launched his last great offensive in the West. By the time the attack was fully understood, three German armies had smashed through thin American lines in the Ardennes forest, forming a massive salient that the newspapers would soon nickname “the Bulge.” It was a shock on a scale few Allied commanders had anticipated.

The Germans believed they had achieved the impossible: complete tactical surprise against an opponent they had come to see as predictable and overly dependent on comfort and material. Their goal was ambitious—drive through Belgium to capture Antwerp, split British and American forces, and force a political settlement.

They never imagined that George Patton would be the one to answer them.

A New Crisis in a Long War

By December 16th, 1944, the war in Europe seemed to be grinding toward an Allied victory. Patton’s Third Army had raced across France after the breakout from Normandy, covering hundreds of miles in four months, liberating vast territory and taking large numbers of prisoners. The German army in the West had been pushed back to its own borders.

Then, in the pre-dawn darkness, 29 German divisions struck the Ardennes sector—a region the Allies had treated as a quiet, secondary front.

American units there were thinly spread, many of them inexperienced or resting after heavy fighting. German troops advanced under cover of bad weather that grounded Allied aircraft. Within hours, armored spearheads were deep into American positions, and the front began to buckle. Villages fell. Road junctions changed hands. Maps at headquarters were suddenly full of question marks.

By the time Eisenhower’s staff grasped the scope of the assault, the Germans had punched some 20 miles into Allied territory and were still moving.

It was in this moment that Eisenhower convened a conference near Verdun on December 19th—a meeting that would determine the Allied response to the crisis.

Patton: Prepared Long Before the First Shot

To the other generals around the table, the situation was alarming and confusing. Units were reporting from unexpected directions, if they could report at all. Communications were frayed. The size and direction of the enemy thrust were still being pieced together.

Patton was the exception.

For him, the Ardennes attack was not a complete surprise. His intelligence officers had noticed unusual German movements and radio silence weeks earlier. While others dismissed these hints as defensive repositioning, Patton had already ordered his staff to draw up contingency plans for a sudden shift of his army to the north.

He walked into the Verdun meeting with three separate plans in his briefcase.

When Eisenhower asked, almost as a test, “How soon can you turn your army and attack to the north?”, the answers around the room hovered in the range of days or more. The scale of such a maneuver—pivoting entire divisions, rerouting supplies, changing axes of advance—was daunting.

Patton said he could attack with three divisions in 48 hours.

Some thought he was exaggerating. Others suspected he had misunderstood the question. He had not. Patton had already put the first steps in motion.

His confidence was not reckless bluster. It was grounded in weeks of preparation: scouting routes, earmarking units for quick movement, and mentally rehearsing the enormous logistical effort required. Where others saw chaos, he saw an opportunity—to strike at the base of the German advance while it was still forming.

A Bold Plan Against a Flawed Strategy

Hitler’s offensive, for all its daring, was built on fragile foundations.

The German plan depended on speed. Fuel supplies were limited; their armored columns had only enough to drive a handful of days before they would need to capture Allied stocks. The winter weather that helped them initially—by grounding Allied aircraft—could not last forever. Once skies cleared, Allied air power would again become a decisive factor.

In effect, the Germans were running on a clock. Every day of delay hurt them more than it hurt their opponents.

Patton immediately recognized this. Instead of trying to blunt the German attack head-on at its strongest point, he proposed to strike its flank and base. By driving north with multiple divisions, he aimed to relieve the encircled town of Bastogne and simultaneously threaten to cut off the leading German units from their supply lines.

It was a classic application of maneuver warfare: attack the weak point that holds the strong point together.

The concept was straightforward on paper. The execution, especially in winter, was anything but.

“Play Ball”: The Army Begins to Turn

After the Verdun meeting, Patton telephoned his headquarters and gave a prearranged code phrase: “Play ball.”

With those two words, the Third Army’s complex emergency plans sprang into action.

Orders rolled out across France and Luxembourg. Tank and infantry divisions that had been facing east toward Germany began to pivot north. Over snowy roads and through bitter cold, columns of vehicles moved in staggering numbers—trucks, halftracks, tanks, artillery, fuel carriers, ambulances. Supply units rerouted. Field kitchens followed.

In a matter of hours, a massive war machine began to change direction.

The numbers hint at the scale. Tens of thousands of vehicles, more than 100,000 troops, and some 60,000 tons of supplies were involved. Units that had been attacking now had to move laterally, without losing cohesion or combat capability, over distances that would challenge even peacetime planners.

They did it in roughly 72 hours.

It was one of the most complex and rapid changes of direction attempted by any army in the war. And it happened under constant time pressure, in the depths of a European winter, while the enemy was still advancing.

Winter: The Second Enemy

The weather that had initially favored the Germans did not spare the Americans during their march north.

Temperatures hovered well below freezing. Snow obscured vision and made roads treacherous. Many soldiers lacked proper winter clothing. Engines refused to start unless they were run periodically through the night to keep oils from congealing.

Weapons froze. Fingers went numb. A long march in such conditions is punishing even without an enemy waiting at the end of it.

Yet Patton insisted on being out in front, exposed to the same cold and danger as the men. He rode in an open jeep in all but the worst conditions, bundled in a heavy coat but otherwise unprotected from the elements. It was not theatrics; it was deliberate leadership. The sight of their commander traversing the same icy roads, enduring the same bitter wind, mattered deeply to the soldiers.

Stories quickly spread through the ranks about his visits, his short speeches, his refusal to hide in a warm headquarters. The Third Army, already proud of their record, took fresh strength from the sense that their leader believed they could accomplish something unprecedented.

That belief was contagious.

Bastogne: A Symbol and an Objective

At the center of the growing German bulge lay the town of Bastogne—a crucial road junction and the focus of some of the fiercest fighting in the battle.

American paratroopers and other units had been surrounded there, cut off by the German advance. Their defense, under Brigadier General Anthony McAuliffe, became legendary—especially after his one-word reply, “Nuts,” to a German surrender demand. But even the most determined defense can only last so long without relief.

Patton’s advancing troops aimed like a spear toward Bastogne.

On December 22nd, they launched a major assault along a wide front under heavy snow. Tanks and infantry pushed forward against determined resistance. German forces, surprised that any large-scale maneuver was even possible in such weather, were forced to divert reinforcements and resources just to keep their flanks from collapsing.

The following days saw intense, close-quarter fighting. Tigers and Panthers clashed with Shermans and tank destroyers across frozen fields and among small villages blackened by shellfire. Progress was sometimes measured in yards, not miles.

Patton understood that the battle was as much about momentum as geography. Every gain, every attack, even when it did not immediately break the line, contributed to an overall shift in initiative.

He also understood, very practically, that he needed the weather to change.

A Prayer and Clear Skies

Patton’s faith, like his personality, was intense and unconventional. He believed in both hard preparation and in seeking divine favor.

In the midst of the Ardennes crisis, he asked his chaplain, Colonel James Hugh O’Neill, to write a special prayer for improved weather. Copies were printed and distributed throughout the Third Army:

“Grant us fair weather for battle…”

Whether by coincidence or meteorological inevitability, the skies began to clear not long afterward. When they did, Allied aircraft—grounded for days by low clouds and snow—returned in force.

Fighter-bombers and medium bombers fell upon German columns and supply routes. Tanks moving along narrow forest roads suddenly found themselves under attack from above as well as from the front. Trucks carrying fuel and ammunition burned. The German logistical ticking clock sped up.

The combination of Patton’s ground offensive and renewed Allied air power turned the situation inside out. What had begun as a confident German thrust now became a struggle to escape encirclement and avoid collapse.

Breaking the Encirclement

On December 26th, elements of the Fourth Armored Division finally broke through to Bastogne, making contact with the defenders after days of persistent assault.

The corridor they opened was narrow and vulnerable, but it was enough. Supplies could move in. Evacuation of the wounded became possible. The symbolic and strategic achievement was enormous: Bastogne had held, and now it was no longer isolated.

For many commanders, that alone would have been enough—a successful relief mission under appalling conditions.

Patton saw it as only the beginning.

With the German advance stalled, their armored spearheads overextended, and their logistics strained, he pushed for continued offensive action. The goal was not just to restore the original line but to punish the German audacity so severely that they could not mount another major offensive in the West.

As he famously told Bradley: “They’ve stuck their head in the meat grinder, and I’ve got hold of the handle.”

The weeks that followed were grueling. Clearing the bulge meant fighting through towns and woods under ongoing winter weather. Both sides suffered heavily. American and German units struggled not only against each other but against frostbite, exhaustion, and the psychological toll of constant combat.

By mid-January 1945, American forces advancing from north and south met near the town of Houffalize. The salient was sealed. The front line, though reshaped, was restored. The German offensive had failed.

Aftermath: A Final Turning Point

The cost of the battle was terrible on all sides. But its strategic impact was clear.

Germany had committed some of its last operational reserves to an offensive that did not achieve its aims. They lost irreplaceable men, tanks, vehicles, and aircraft. More importantly, they lost the ability to seize the initiative in the West ever again.

For the Allies, the Battle of the Bulge became proof of resilience. Units that had been surprised, pushed back, and battered in the first days reorganized, fought back, and prevailed. The American army that had once been dismissed as inexperienced and reliant on material proved it could endure and overcome a major crisis.

Winston Churchill, not quick to offer unqualified praise, later called it “undoubtedly the greatest American battle of the war.” He was referring to the scale of the engagement and the extent to which American troops bore the brunt of it. But implicit in that statement was also recognition of the leadership that made the turnaround possible.

Patton’s role was central. His ability to anticipate a possible crisis, plan for it, and then execute a massive maneuver under the worst conditions helped prevent a temporary setback from turning into something far worse.

A Life Prepared for One Moment

For George Patton, the Ardennes was not just another campaign. It was, in many ways, the test he had spent his life preparing to confront.

He had always believed he was destined to command in a moment of supreme danger. In the winter of 1944–45, with enemy forces driving into the Allied line and hope wavering, he was given that chance.

His actions in those weeks demonstrated more than aggressiveness. They showed foresight, organizational skill, psychological insight, and a willingness to trust his soldiers with missions that others thought impossible. He did not win the battle alone—no general ever does—but his decisions shaped its outcome at critical junctures.

The Germans who had once regarded American forces as clumsy and overly cautious came away with a very different view. Many would later single out Patton as the Allied commander they most respected—and most feared—because he thought and fought in ways closest to their own doctrine of rapid, decisive operations.

It is tempting to remember the Battle of the Bulge solely through images of snow, forests, and encircled paratroopers. Those are powerful symbols. But behind them lies a less visible story: of staff officers quietly drawing contingency plans, of dispatch riders and radio operators relaying sudden orders, of drivers coaxing vehicles along icy roads, and of a general who had his army ready to move before most people realized they needed to.

When fate called in the Ardennes, George Patton did not improvise from a blank page. He opened a book he had been writing his entire life—and turned the crisis into a turning point.

News

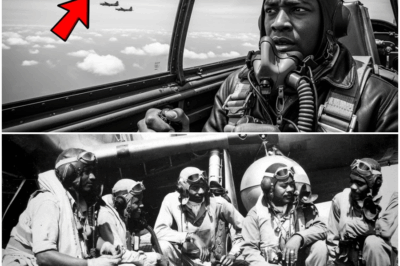

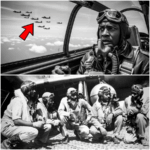

THE TUSKEGEE GAMBLE: The Moment One Pilot Risked Everything With a ‘Fuel Miracle’ to Save 12 Bombers From Certain Death.

Thirty thousand feet above the Italian countryside, Captain Charles Edward Thompson watched the fuel needle twitch and understood, with a…

THE ‘STUPID’ WEAPON THAT WON: They Mocked His Slingshot as a Joke—But It Delivered the Stunning Blow That Silenced a German Machine-Gun Nest.

In the quiet chaos of Normandy’s hedgerow country, where every field was a trap and every hedge could hide a…

THE HIDDEN MESSAGE IN A MARINE’S PORTRAIT: It Looked Like a Standard Family Photo, But One Tiny Detail in Their Hands Hides a Staggering Secret.

In a small studio at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, a photographer captured what looked, at first glance, like a routine…

This Farm Boy Fixed a Jammed Machine-Gun — And Changed the Battle

On a foggy French hillside in the early hours of September 13, 1944, a 19-year-old farm boy from Iowa found…

They Gave a Black Private a “Defective” Scope — Until He Out-Sniped the German Elite in One Hour

On a cold October morning in 1944, the fog over the Moselle Valley hid more than just treelines and concrete…

THE DAY THEIR WORLD CRUMBLED: German Women POWs See Black American Soldiers for the First Time—And the Shockwave Changes Everything.

On a muddy patch of ground outside Remagen in March 1945, two worlds that had been taught to despise one…

End of content

No more pages to load