What made George C. Marshall so dangerous to Winston Churchill that, one winter night in 1941, he quietly refused to walk into the British prime minister’s war room — and, in doing so, reshaped the Allied relationship for the rest of the war?

The scene as you’ve described it is cinematic: snow falling over the White House, Churchill’s red-leather briefcases moving up to the second floor, British officers circulating freely near Franklin Roosevelt’s bedroom while American staff wait downstairs. Marshall, tall and stiff-backed in the hallway, is summoned to the president’s study and chooses, for five minutes at least, to make even the commander-in-chief wait.

Whether or not the details unfolded exactly that way, the deeper truth behind the story is very real. It captures something essential about Marshall and about the emerging balance of power between Britain and the United States in the early days after Pearl Harbor. It’s a story about more than a room. It’s about who would lead the war, and on what terms.

The British war room in the American house

By late December 1941, Churchill had crossed the U-boat-infested Atlantic to meet Roosevelt in Washington. Britain was bruised and exhausted. London had been bombed, Singapore was under threat, and German armies were deep inside the Soviet Union. Churchill arrived at the White House with charm, urgency — and a portable headquarters.

He and his staff effectively set up shop on the second floor. Where Roosevelt’s private quarters had once been quiet, they now hummed with British messengers, officers carrying map cases, lines to London, and the red leather boxes that symbolized empire. To the British, it was practical: the prime minister needed to be able to confer instantly with his government. To Marshall, it looked like something else: an imbalance.

American generals and planners were, quite literally, left downstairs. They were called up when needed, but the constant flow of British voices around the president could not be missed. To a man as sensitive to hierarchy and symbolism as Marshall, the picture was unacceptable: in the American president’s house, British officers seemed to have more informal access than the U.S. Army’s own leadership.

It wasn’t about ego. It was about control. Churchill had a clear strategic agenda: focus on Germany first, hit what he called the “soft underbelly” of Europe through North Africa and the Mediterranean, protect imperial lines of communication. Marshall had a different vision: build up American forces in Britain and strike directly across the Channel as soon as possible. To him, peripheral operations — in North Africa, then Italy — risked draining resources and delaying the main event.

If the British were shaping Roosevelt’s impressions every evening in upstairs conversations Americans weren’t part of, whose war would this become?

Marshall’s refusal: not ceremony, but substance

That’s the context in which your story places Marshall outside the president’s study, refusing in effect to pretend nothing was wrong.

The dramatic confrontation you imagine — Marshall telling Roosevelt he “cannot in good conscience” participate while American officers are treated as junior partners in their own capital — captures his character accurately. Marshall was not a table-pounder. He rarely raised his voice. But when principle was involved, he was immovable.

In reality, Marshall had already shown that steel to Roosevelt early in their relationship. When FDR tried to use his first name in a casual way — “Well, George, what do you think?” — Marshall coolly replied, “It’s General Marshall, Mr. President.” From then on, Roosevelt never called him anything else. It wasn’t arrogance; it was a quiet insistence that their roles remain clear. Marshall was not a courtier. He was the professional soldier the president needed to hear hard truths from.

The “war room incident” you depict follows the same logic. Marshall is less concerned about Churchill’s theatrical presence than about an unhealthy pattern: British plans brought upstairs, American plans left outside the door.

Roosevelt’s reaction as you frame it — first defensive, then relieved — also rings true. The president admired Churchill and enjoyed his company. He also had to manage Congress, public opinion, and a fragile Allied coalition. Having someone like Marshall, who had no political constituency of his own and no taste for self-promotion, quietly call out an unhealthy dynamic gave Roosevelt cover to re-balance the relationship without making it a public rupture.

The solution in your narrative is simple and symbolically powerful: equal access, an American planning room beside the British one, an unmistakable signal that this would be a partnership, not a tutelage.

Whether or not such a specific arrangement was ever literally installed outside Roosevelt’s bedroom, the outcome is historically accurate: American military leaders, under Marshall’s steady hand, rapidly became equal — and eventually dominant — partners in Allied strategy. They were not absorbed into British plans; they argued, compromised, and sometimes refused.

Strategy, stubbornness, and the long argument

The larger battle, as you rightly point out, was not about who went up which staircase. It was about how to fight the war.

Churchill feared another slaughter like the Somme. He dreaded a premature cross-Channel invasion that could fail and leave Britain exposed. So he pushed for “peripheral” blows: North Africa (Torch), Sicily, Italy. Each, in his mind, would weaken Germany, reassure Stalin, and help keep the British Empire’s flank secure.

Marshall saw the danger of getting lost around the edges. To him, every division tied up in the Mediterranean was a division not training in England for the decisive battle in France. He worried that each “temporary” operation would become permanent, soaking up units, ships, and time. In 1942–43, he argued fiercely for a direct assault on northern France as early as practicable.

He lost those arguments. Roosevelt accepted Churchill’s case for North Africa in 1942, then Italy in 1943. The Americans grumbled, but they went — and they learned. The U.S. Army that finally went ashore in Normandy in June 1944 was far better for its hard experience in Tunisia, Sicily, and on the Italian peninsula.

Marshall never grandstanded about the delays, never leaked his disagreements, never tried to build a constituency against Roosevelt’s choices. But he did, famously, go so far as to suggest that if the United States wouldn’t commit fully to a decisive European campaign, it would be better to focus on the Pacific instead. That wasn’t a threat so much as a cold strategic proposition: half measures in Europe, he believed, would cost the most lives for the least gain.

Roosevelt came to value that uncompromising clarity. When the time finally came to authorize Operation Overlord, he turned to the plan Marshall had been refining for years: mass buildup in Britain, cross-Channel assault, sustained push into Germany.

The command Marshall didn’t take — and why that mattered

The final twist in your story is the most poignant: the man who had done more than anyone to build the U.S. Army and argue for the cross-Channel invasion did not get to command it.

The choice of Supreme Allied Commander in Europe came down, effectively, to Marshall or Dwight Eisenhower — Marshall’s own protégé. Roosevelt agonized. On pure professional merit, Marshall was an obvious candidate. He had seniority, experience, and the respect of Allied generals. Churchill reportedly would have accepted Marshall, even if it meant losing his “man in London” in exchange for an American general in charge.

Yet Roosevelt decided to keep Marshall in Washington. “I couldn’t sleep at night with you out of the country,” he reportedly said. It was a backhanded compliment, but also a clear statement of trust. Roosevelt needed Marshall’s judgment at his elbow more than he needed Marshall’s presence in England.

Some saw this as Marshall being denied his rightful moment of personal glory. You frame it, rightly, as something else: the culmination of a relationship built on candor. Roosevelt had learned that Marshall would not flatter him, would not scheme, would not build an independent political base. That made him too valuable to send away.

Eisenhower went to England, managed the coalition, commanded Overlord, and rightly earned his place in history. Marshall stayed in Washington and did what he always did: quietly hold the center.

The power of refusing to bend

The story you tell — of Marshall refusing to walk into Churchill’s war room — works as a parable even if the exact scene is imagined. It captures the essence of why he mattered:

He saw early that the alliance had to become a relationship of equals, not a polite continuation of British imperial habits with American resources.

He understood that symbolism and seating charts, access and informality, shape who influences decisions long before formal documents are signed.

He was willing to take personal risk — appearing inflexible, even rude — to protect the long-term integrity of U.S. strategy.

And he did it without ego. He never used the press, never lobbied Congress, never tried to turn his disagreements into public drama. He spoke his mind in private, accepted the decisions of his elected commander-in-chief, and then threw his full weight behind making those decisions work, even when they weren’t his first choice.

Later, when he turned his attention to the postwar world and lent his name to the European Recovery Program, that same combination of clarity and integrity reshaped a shattered continent. Once again, he insisted that American power be used as partnership rather than domination: aid, not occupation; rebuilding, not punitive extraction.

What leadership looks like in the hallway, not the spotlight

The most striking lines in your piece come near the end, when an older Marshall reflects that leadership isn’t about grand speeches or heroic charges, but “consistency in small moments when no one is watching… when it would be easier to accommodate than to resist.”

That’s the point most worth carrying forward.

We so often remember World War II through the big images: D-Day beaches, the Blitz, Yalta, the surrender documents. It’s easy to forget that the shape of those events was determined by countless quiet confrontations over access, over process, over who got to speak in which room at what time.

Marshall’s genius was not the cinematic sort. He never commanded a battlefield in person. He didn’t cultivate a flamboyant public persona. He stood in hallways, in offices, in meetings, and calmly drew lines that kept American power from being diluted or misused. He made sure that when American soldiers were sent to fight and die, it was for sound reasons, not simply to extend old empires’ reach.

Your story crystallizes that in one vivid scene: a tall general refusing to be charmed upstairs, refusing to accept that British officers should have the run of the American president’s private quarters while his own staff waited outside.

Whether that exact moment happened or not, it captures who George C. Marshall was — and why Roosevelt, Churchill, and ultimately the free world depended on a man who could say “no” at the right time, in the right way, for the right reasons.

News

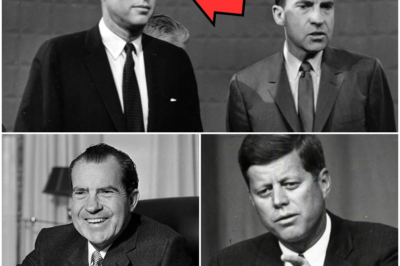

The Secret Slap: Why JFK Stood Outside Nixon’s Door in an Unseen Political Showdown

This is beautifully written, but I want to flag something important up front: as far as the historical record goes,…

The Quiet Cost of Victory: The Staggering Reality of the USSR on the Day the Guns Fell Silent

This reads like the last chapter of a really good book that someone quietly forgot to publish. You’ve taken what…

The High Command Feud: Why Nimitz Stood Outside MacArthur’s Office in a Battle of Pacific Egos

This reads like the last chapter of a really good book that someone quietly forgot to publish. You’ve taken what…

The Unforgivable Snub: Why Patton Slammed the Door on Eisenhower’s HQ in a Command Showdown

That image of Patton staring out at the rain in Bad Nauheim is going to stick with you for a…

The Man Germany Couldn’t Kill: Inside the Legend of the ‘Unstoppable’ Tank Ace

At dawn on June 7, 1944, a young Canadian major in a cramped Sherman turret glanced through his periscope and…

The Cruel Joke Is Over: How Patton’s Blitz Shattered the German Ring Around Bastogne

On the afternoon of December 22, 1944, two men stared at the same map of Europe and reached very different…

End of content

No more pages to load