The last words I ever heard in my classroom, after forty-two years of chalk dust and scraped knees, were “Whatever, old man.”

The bell hadn’t even finished its ragged, shrieking cry before the boy, Brayden, was gone. A flash of sneakers that cost more than my first car and the scent of some sugary spray deodorant. The words, not shouted but tossed over a shoulder with the casual indifference of a discarded gum wrapper, just hung there in the air.

I stood behind the old oak desk I’d inherited from Mr. Abernathy back in ’78. I ran a hand over its surface, a roadmap of my life. I knew every scar: the faint circles from a thousand coffee cups, a deep gouge from a protractor used as a dagger in some long-forgotten pirate war, the nearly invisible initials of a girl who’s probably been a grandmother for a decade. The wood grain felt as familiar as the lines on my own face. Forty-two years. It doesn’t feel real to say it.

I looked at the empty space where Brayden had sat. He wasn’t a bad kid, not really. He was just… empty. His eyes, when they bothered to look up from that little glowing rectangle in his hands, held a flat, uncurious sheen. To him, I wasn’t the man who taught his mother how to multiply or his uncle how to find Egypt on a map. I was just an obstacle. An old, boring man standing between him and summer.

My gaze drifted to the window, past the manicured lawn the school district is so proud of, to the cracked asphalt of the playground. A ghost of a memory flickered, so sharp it made my chest ache. 1985. A skinny kid named Michael, all elbows and ears, with a worn-out Star Wars lunchbox and a stutter that made the other boys cruel. Michael’s father had just been laid off from the steel mill, a wound the whole town was bleeding from.

One spring afternoon, during recess, I’d watched from this same window as the bigger boys cornered Michael by the swing set. I was about to step outside, to use that voice that could stop a spitball fight at fifty paces, when I saw it. Michael didn’t cower. He just stood there, his small jaw set, and took the shoving. Never said a word.

Later, as the class filed back in, reeking of playground dust and freedom, Michael hung back. His knuckles were raw, and there was a tear in the knee of his jeans. He walked right up to my desk, looked down at his scuffed shoes, and placed a single, ragged dandelion on the blotter.

“For you, Mr. C,” he’d stammered, the ‘C’ catching in his throat. “For… for not yelling.”

I kept that dandelion. Pressed it between the pages of a heavy history textbook. It’s still in the bottom drawer of this desk, a fragile, faded ghost of a thing. A payment made in the only currency a broke, proud little boy had. A currency of respect.

I opened the drawer now. My personal effects were mostly packed in a cardboard box. My coffee mug, a picture of my late wife, a stack of the best-written student reports. Beneath them was the textbook. I opened it, and there it was. A pale, tissue-thin silhouette.

I thought of Brayden’s glowing rectangle, a device that could show him the whole world in an instant. And I thought of Michael’s dandelion, a universe of meaning plucked from a cracked playground. One was a window to everything, and meant nothing. The other was a weed, and meant everything.

I closed the book, gently, and placed it in the box. It wasn’t Brayden’s fault, I told myself. You can’t value something you’ve never been taught to see. You can’t miss a silence you’ve never known. I wasn’t angry, not anymore. Just tired. A deep, seismic tired that came from holding the line for forty-two years, only to watch the line disappear.

I picked up the box, the weight of it a final, physical burden. I didn’t look back at the empty desks or the clean-swept floor. I just walked out, turned off the lights, and closed the door on a room full of ghosts, leaving it to a world that no longer knew their names.

News

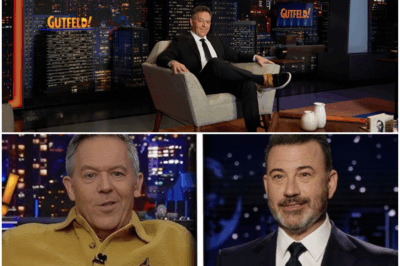

Greg Gutfeld vs. Jimmy Kimmel: Why Fox News’ Late-Night King Reigns Supreme

Greg Gutfeld vs. Jimmy Kimmel: Why Fox News’ Late-Night King Reigns Supreme In the ruthless, competitive world of late-night television,…

Fox News Faces Backlash After Jesse Watters and Julie Banderas Comments About Barron Trump

Fox News Faces Backlash After Jesse Watters and Julie Banderas Comments About Barron Trump Fox News is once again at…

Shockwaves in Television: How The Charlie Kirk Show Shattered the Rules and Redefined Media Power

Shockwaves in Television: How The Charlie Kirk Show Shattered the Rules and Redefined Media Power Shockwaves rippled through ABC headquarters…

Sandra Smith Joins Greg Gutfeld on The Five: A Bold New Era for Fox News

Sandra Smith Joins Greg Gutfeld on The Five: A Bold New Era for Fox News In a surprising move that…

“Shockwaves Across Television: Jeanine Pirro Joins Erika Kirk and Megyn Kelly on The Charlie Kirk Show — Fans Call It ‘The Most Powerful Program Ever,’ ABC Executives Panic as Unthinkable Happens With Over 1 Billion Views in Days

Trump Taps Jeanine Pirro as DC Prosecutor: A Media Earthquake and the Rise of The Charlie Kirk Show When Donald…

What would you do if, upon entering prison for the first time, everyone thought you were weak, not knowing you could defeat them single-handedly? When Tomás walked through the rusty gates of the Santa Cruz penitentiary, the air seemed heavier

What would you do if when you entered prison for the first time everyone thought you were weak without knowing…

End of content

No more pages to load