The Climb That Could Not Fail: The Rangers at Pointe du Hoc

At 7:10 a.m. on June 6, 1944, Lieutenant Colonel James Earl Rudder stood at the base of a sheer limestone cliff on the coast of Normandy, watching grenades tumble down toward his men. The ropes meant to carry the Rangers upward were soaked with seawater, too heavy to throw, too slick to climb. The ladders had not yet arrived. Above them, German defenders occupied fortified positions carved into the cliff top.

Behind Rudder lay the English Channel. Ahead of him rose Pointe du Hoc.

For a brief moment, the mission appeared to be collapsing.

A Mission Defined by Necessity

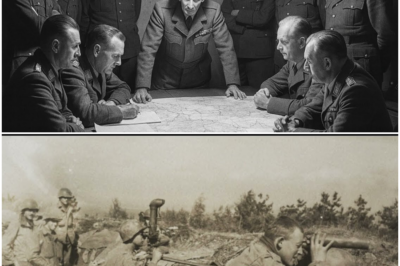

Months earlier, in a crowded briefing room in London, Rudder had been told that the success of the Normandy landings depended in part on a single point of land jutting into the sea. Atop Pointe du Hoc, intelligence believed, sat six French-made 155-millimeter artillery pieces with the range to strike both Omaha and Utah beaches.

If those guns remained operational, they could inflict devastating losses on Allied forces landing below.

Rudder’s orders were unambiguous: land at the base of the cliffs, scale them under fire, destroy the guns, and hold the position until reinforcements arrived. The cliffs rose nearly one hundred feet, reinforced with barbed wire, minefields, and concrete emplacements. Roughly two hundred German troops defended the area.

The briefing concluded with a warning few commanders ever forget: this would likely be the most difficult mission of his career.

Crossing the Channel

Before dawn on June 6, Rangers from the 2nd and 5th Battalions boarded landing craft and amphibious vehicles in heavy seas. Weather conditions favored the defenders. A strong tidal current pushed the small craft eastward, scattering the formation.

Supplies were lost when overloaded craft swamped and sank. Men were rescued, but equipment vanished beneath the waves. By the time the shoreline emerged through smoke and haze, Rudder knew something was wrong.

They were off course.

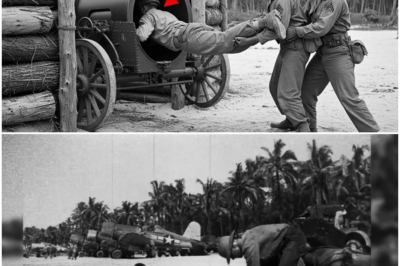

German fire intensified as the Rangers closed the final distance. Mortars and automatic weapons tore into the water. One amphibious vehicle carrying ladders was hit and sank. Others struggled ashore only to stall in craters and sandbars.

The Rangers disembarked under fire and ran across open ground toward the base of the cliffs.

At the Foot of the Wall

German defenders waited until the Rangers were within range, then opened fire in full. As the Rangers hugged the cliff face for cover, grenades and debris rained down. Attempts to fire rocket-launched ropes failed; most fell short and bounced back.

Reports came quickly: the ropes were useless, too heavy from seawater to deploy effectively.

For a moment, there appeared to be no viable way up.

Naval gunfire from offshore began pounding the cliff face, dislodging rock and earth. As dust settled, Rudder noticed something unexpected: the bombardment had created a sloping mound of debris at the cliff’s base.

It was not a ramp—but it was enough.

The Decision to Climb

Rudder ordered the ladders forward.

Under fire, Rangers assembled the sections, working together with practiced precision despite explosions and gunfire. Technician Fifth Grade George J. Putzek climbed first, anchoring the ladder at the top. Others followed in quick succession.

Within minutes, Rangers crested the final sixty feet and spilled onto the plateau.

The impossible climb had been completed.

A Troubling Discovery

Once atop Pointe du Hoc, the Rangers moved rapidly through trenches and craters, clearing German positions with grenades and small-arms fire. Resistance was fierce but disorganized. The defenders had not expected attackers to reach the summit so quickly.

As Company D advanced toward the artillery positions identified in pre-invasion intelligence, First Sergeant Leonard Lomell made a startling discovery.

The guns were gone.

In their place stood wooden decoys.

The artillery had been moved inland.

The mission, it turned out, was not yet complete.

Securing the Point

Rudder, already wounded, established a command post in one of the captured bunkers and attempted to contact Allied headquarters. His message was blunt: Pointe du Hoc was secure, but the Rangers were badly depleted and needed ammunition and reinforcements.

The reply was equally blunt: no reinforcements were available.

The Rangers were on their own.

Despite this, Rudder ordered patrols inland to locate the missing artillery. Lomell and Staff Sergeant Jack Kuhn moved through hedgerows and orchards, eventually locating the guns concealed along a road.

Using thermite grenades, they disabled all six artillery pieces, rendering them permanently inoperable.

The original threat to Omaha and Utah Beaches was eliminated.

Holding Against the Counterattack

Destroying the guns solved one problem. Holding Pointe du Hoc created another.

As night fell, the Rangers prepared for counterattacks. German forces probed their defenses repeatedly, attacking under cover of darkness with whistles, flares, machine guns, and mortars.

The fighting was brutal and close. Ammunition ran low. Casualties mounted. At one point, the German assault briefly overran Ranger positions, forcing a hasty withdrawal and reorganization.

By dawn on June 7, Rudder had fewer than ninety able-bodied men holding the point.

Yet the Germans did not press further. The Rangers’ resistance had disrupted the defenders’ coordination and sapped their will to continue.

On June 8, American forces advancing from Omaha Beach finally reached Pointe du Hoc.

The mission was complete.

Cost and Consequence

Of the Rangers who landed under Rudder’s command, seventy-seven were killed and 152 wounded. Rudder himself had been wounded three times during the assault and defense.

The casualty rate was severe—but the mission succeeded.

The feared artillery at Pointe du Hoc never fired on the invasion beaches. The cliffs did not become a killing ground for Allied troops. The Normandy landings gained the foothold needed to push inland.

The Rangers’ role at Pointe du Hoc was not the largest action of D-Day, but it was one of the most consequential.

Leadership Under Impossibility

What distinguished the assault at Pointe du Hoc was not flawless execution. Plans failed. Equipment was lost. Intelligence proved incomplete.

What mattered was adaptability.

Rudder did not freeze when the ropes failed. He did not abandon the mission when the guns were missing. He adjusted, redirected, and pressed forward under conditions where hesitation would have meant failure.

The Rangers followed not because the situation was favorable, but because retreat was not an option.

Memory at the Cliff’s Edge

Today, Pointe du Hoc stands quiet, its bomb-scarred landscape preserved as a memorial. Concrete bunkers remain shattered. Craters dot the ground. A monument honors the Rangers who climbed where climbing should not have been possible.

Eighty years later, the cliffs still rise steeply from the sea.

They remind visitors not only of courage, but of the cost of decisions made under fire—decisions where delay would have changed history.

The Rangers who scaled Pointe du Hoc did not know whether reinforcements would come. They did not know if the guns were still there. They only knew the mission could not fail.

And so they climbed.

News

The ‘Suicide’ Dive: Why This Marine Leapt Into a Firing Cannon Barrel to Save 7,500 Men

Seventy Yards of Sand: The First and Last Battle of Sergeant Robert A. Owens At 7:26 a.m. on November 1,…

Crisis Point: Ilhan Omar Hit With DEVASTATING News as Political Disasters Converge

Ilhan Omar Hit with DEVASTATING News, Things Just Got WAY Worse!!! The Walls Are Closing In: Ilhan Omar’s Crisis of…

Erika Kirk’s Emotional Plea: “We Don’t Have a Lot of Time Here” – Widow’s Poignant Message on Healing America

“We Don’t Have a Lot of Time”: Erika Kirk’s Message of Meaning, Loss, and National Healing When Erika Kirk appeared…

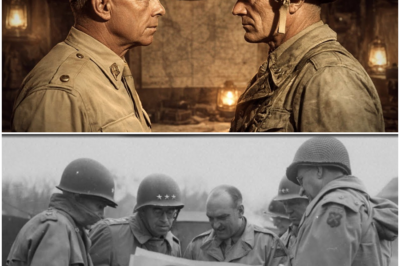

The Führer’s Fury: What Hitler Said When Patton’s 72-Hour Blitzkrieg Broke Germany

The Seventy-Two Hours That Broke the Third Reich: Hitler’s Reaction to Patton’s Breakthrough By March 1945, Nazi Germany was no…

The ‘Fatal’ Decision: How Montgomery’s Single Choice Almost Handed Victory to the Enemy

Confidence at the Peak: Montgomery, Market Garden, and the Decision That Reshaped the War The decision that led to Operation…

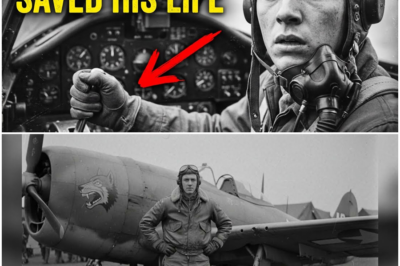

‘Accidentally Brilliant’: How a 19-Year-Old P-47 Pilot Fumbled the Controls and Invented a Life-Saving Dive Escape

The Wrong Lever at 450 Miles Per Hour: How a Teenager Changed Fighter Doctrine In the spring of 1944, the…

End of content

No more pages to load