The jeep rolled to a stop, and George S. Patton Jr. refused to go any farther.

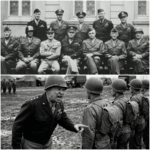

On the surface, it was nothing: a vehicle halting two hundred yards from a canvas tent on a dusty Sicilian afternoon in August 1943. But to the man in the passenger seat—a three-star general with ivory-handled revolvers and a volcanic sense of pride—those two hundred yards were not just ground. They were a line he felt he had been pushed across and was now quietly, stubbornly pushing back against.

Inside the tent ahead, waiting, was Omar N. Bradley: former student, now rising star, soon to be Patton’s superior. Between them lay more than dust and heat. There lay humiliation, scandal, and the awkward collision between two very different visions of what a modern general should be.

This is the story of that walk, and what it reveals about Patton, Bradley, and the changing nature of command in the Second World War.

A General Who Refused to Be Ordinary

At 57, George Patton saw himself less as a manager and more as a warrior from another age who had been accidentally dropped into the 20th century.

He came from a family steeped in military tradition. He believed in reincarnation and claimed to remember fighting in ancient battles. He had helped design the U.S. Army’s cavalry saber, chased bandits with Pershing in Mexico, commanded tanks in the First World War, and spent the interwar years refining armored doctrine when many still viewed tanks as little more than noisy experiments.

He cultivated an image: polished helmet, riding breeches, twin pistols with pale grips. The theatrics weren’t vanity; they were part of how he inspired his troops and intimidated his enemies. He believed that in war, morale was as much about appearance and gesture as it was about numbers on a chart.

Patton’s early campaigns in North Africa and Sicily reinforced his self-image. After the American defeat at Kasserine Pass in February 1943, he took over a shaken II Corps and, through harsh discipline and relentless drive, turned it into an aggressive, effective formation. In Sicily, his rapid advance, capture of Palermo, and race to Messina showed what American armor could do under bold leadership.

Then he slapped a soldier in a hospital.

The Slaps That Changed Everything

The incidents that nearly destroyed Patton’s career did not happen in a blaze of battle, but in medical tents.

At the 90th Evacuation Hospital, he encountered Private Charles H. Kuhl, sick with malaria and dysentery, feverish and shaking. When Patton asked where he was hit, Kuhl said he wasn’t wounded—he was nervous and couldn’t take it anymore. To Patton, who believed fear must be controlled by will, this sounded like weakness, not illness.

He struck the soldier with his gloves, grabbed him, and dragged him out of the tent, condemning him as a coward in front of medical staff who stood stunned. A week later, at a different hospital, he did something similar to another soldier, this time drawing his pistol in the process.

In both cases, doctors had diagnosed legitimate combat stress and illness. In both cases, Patton reacted through the lens of an older warrior code that saw psychological injury as a failure rather than a wound. In his mind, he was protecting the “brave men” from what he considered contagious fear. In practice, he had publicly assaulted vulnerable soldiers in front of horrified witnesses.

For a short time, the army tried to keep the story contained. But too many people had seen. Word reached journalists. Commentators began to ask why one of America’s most famous generals was striking hospitalized soldiers.

Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Commander, was thrust into a delicate crisis. He needed Patton’s talent—and the effect his name had on German planners who feared what “Old Blood and Guts” might do next. But he also needed to maintain discipline, uphold basic standards of decency, and respond to political pressure from Washington.

Eisenhower’s solution was a compromise: he issued Patton an extremely sharp reprimand and ordered him to apologize—personally and publicly—to the men he had struck and to their units. Patton was not relieved of command, but his reputation and standing were badly damaged.

George Patton, who had built his entire identity around honor, courage, and leadership, found himself shamed and watched.

Bradley: The Quiet Counterpart

Waiting in that tent in Sicily was a man who represented nearly everything Patton resented about modern command: Omar Bradley.

Bradley had been Patton’s student at the cavalry school. He wore glasses, favored plain uniforms, spoke softly, and did not cultivate a dramatic persona. For years, he had been a competent, often overlooked professional—trusted by superiors, respected by peers, but rarely glorified in the press.

Yet it was precisely those understated qualities that made him indispensable as the war expanded. Bradley excelled at planning, coordination, and managing large organizations over time. He understood that in a modern, coalition war, success depended not just on bold attacks, but on supply lines, staff work, and politics.

Eisenhower leaned on Bradley because he could trust him to handle complex, multi-national operations without creating unnecessary controversy. Bradley would not slap patients in front of doctors. He would not make impulsive public statements. He would not outshine allies at press conferences or force his commander to deflect scandals.

In the wake of the hospital incidents, that difference suddenly mattered a great deal.

Bradley’s star rose. He was promoted, first to corps, then to army group command. Patton, meanwhile, found himself under a cloud, his future uncertain.

Two Hundred Yards of Dust and Pride

On the day the jeep rolled to a stop, these tensions were simmering just below the surface.

Bradley had requested a meeting. Operationally, it was routine: coordination between Patton’s Seventh Army and the formations Bradley had recently overseen, discussion of German withdrawal routes, and planning for the push to Messina.

Inside the tent, Bradley checked his watch, aware that he was meeting not just a subordinate, but a former mentor whose pride had been badly wounded. Outside, in the heat and dust, Patton sat unmoving.

For weeks, he had endured formal rebuke and informal sidelong glances. Rumors about the slapping incidents circulated. He knew he was under scrutiny from above and whispers from below. And now he was expected to drive up to a tent and receive instructions from a man he still saw—in his bones—as the student, not the master.

He made a decision.

“Drive to the entrance,” he finally told Sergeant John Mims, his driver, in a low, controlled voice that signaled barely contained anger. “Stop there. I’ll walk from the perimeter.”

Mims said nothing, which was the safest course when Patton’s jaw tightened like that. He eased the jeep forward until it reached the edge of Bradley’s headquarters area and stopped.

Patton climbed out. He ignored the guards snapping to attention. He did not acknowledge his own aide. He set his shoulders and began walking.

Every step across that Sicilian dust was doing two jobs at once. On one level, it carried him toward a necessary meeting. On another, it broadcast a message to everyone watching: I am here because I have to be, not because I accept this.

It was a small act of rebellion—not disobedience, but visible resentment. The kind of gesture a man makes when he cannot openly refuse, but refuses to come quietly.

A Relationship Curled at the Edges

Inside the tent, the meeting itself was businesslike and cold.

Bradley laid out movements, supply arrangements, and intelligence. Patton listened, said what he needed to say, and kept his expression carefully neutral. Bradley either missed or pretended to miss the hostility in Patton’s posture.

Near the end, Bradley mentioned something that turned up the pressure another notch: Eisenhower was considering changes in command structure after Sicily. New commands. New hierarchies.

That meant someone would be placed above someone else.

Given the recent scandal, Eisenhower’s irritation, and Bradley’s reputation as a safe pair of hands, Patton could see the future. Bradley would be groomed for the highest levels of command. Patton, no matter how effective on the battlefield, would never be allowed to sit at the very top.

He said nothing in response. But when he turned and walked those two hundred yards back to the jeep, his driver saw that his fists were clenched.

The relationship between the two men—once marked by mentorship and mutual respect—never recovered. Professionally, they continued to cooperate. Personally, the warmth was gone.

Patton saw Bradley as dull, cautious, and overly focused on paperwork. Bradley saw Patton as brilliant but exhausting, a weapon that had to be used but also monitored.

A Phantom Army and a Real One

The events that followed underline the divide.

When planning for the Normandy invasion began in earnest, Patton was given command of the First U.S. Army Group—FUSAG. On paper, it sounded grand. In reality, it was a ghost.

FUSAG existed mainly in the minds of German intelligence analysts and on fake radio nets. Its “divisions” were inflatable tanks, dummy camps, misleading signals. The entire formation was a deception, designed to convince the Germans that the main landings would come at Pas-de-Calais instead of Normandy.

Who better to front such a performance than a general the Germans feared? Patton’s mere presence in southeast England fed the illusion that a massive force under his command was preparing to cross the narrowest part of the Channel.

While he played that role—important in its own way, but removed from real fighting—Bradley received command of the 12th Army Group, the largest American field command in history. When U.S. troops stormed the actual D-Day beaches and pushed inland, they did so under a structure that led to Bradley at the top of the American ground forces.

For a man who measured himself by combat, it was a calculated insult. Necessary from Eisenhower’s point of view, perhaps, but bitter for Patton.

When his real command, Third Army, finally became operational in August 1944, Patton responded like a man released from a cage. The dash across France, the encirclements, the race to the German border—these were his natural language. His calls to Bradley, boasting about crossing the Rhine ahead of the carefully planned British operation, were not just operational reports. They were, on some level, a continuing argument: Look what I can do, if you let me.

Why Patton Couldn’t Be Allowed at the Top

If the story ended there—with the proud warrior sidelined by cautious bureaucrats—it would be easy to cast Patton as a victim. But the reality was more complicated.

Modern war, especially on the scale of the Second World War, required two distinct skill sets:

Leaders who could sense opportunity, accept high risks, and inspire troops to fight through fear—Patton’s realm.

Leaders who could manage alliances, budgets, media scrutiny, and the large, grinding machinery of a global war—Bradley’s strength.

Patton’s slapping of soldiers was not just a private lapse; it was a public act that struck at the idea that ordinary men’s lives and dignity mattered in a democratic army. His later public comments about politics and occupation policies in Germany showed the same tendency to act and speak as if no higher authority existed.

Eisenhower needed Patton on the battlefield. He could not risk Patton at the top of the political-military structure.

Bradley, by contrast, rarely created headlines. He had his critics—some saw him as too cautious. But he understood that wars in free societies are fought not just with tanks and guns, but with public consent. And that consent could be strained by commanders who seemed willing to humiliate the vulnerable or make unilateral political statements.

In that sense, Eisenhower’s choice to place Bradley above Patton was not a denunciation of Patton’s talent. It was an acknowledgment that talent alone, without restraint and awareness of context, was not enough for the very highest command.

Magnificent and Wrong

The image of Patton walking those two hundred yards through Sicilian dust has endured because it captures a particular kind of tragic heroism.

On one level, it was petty: a senior officer making a point about his pride in a way that did nothing to change decisions already made. On another level, it was undeniable: one of the most gifted combat commanders of the age refusing, in his bones, to accept that he must defer to someone he believed less capable in battle.

He was wrong about what modern war required. But he was magnificent in the intensity of his conviction.

History has largely embraced both sides of him. We study Patton’s campaigns for their speed, imagination, and audacity. We also use his life as a case study in how personality and pride can both empower and limit a leader.

Bradley lived long enough to help write the story, appearing in documentaries and memoirs as the steady hand. Patton died in 1945 after a car accident in Germany, his narrative forever frozen in the war years—never softened, never tempered by older age.

But if you want to understand why Patton’s story feels so compelling, return to that moment when the jeep stopped.

He could have driven to the tent, stepped out, and pretended that nothing had changed. Instead, he chose to walk—every step a silent argument against the world as it was becoming.

An army fighting for democracy could not be shaped solely around men like him. But it could never have won without them. Those 200 yards hold that contradiction in a single line.

News

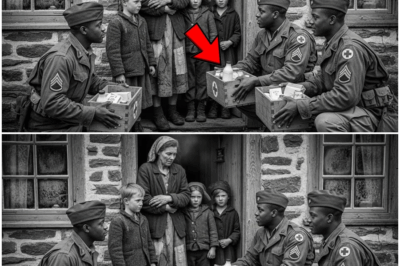

“I Thought They Were Devils,” German Woman Said After Black Soldiers Saved Her Starving Family

The chimneys in Oberkers had been cold for weeks. Snow lay heavy on the sagging roofs of the small German…

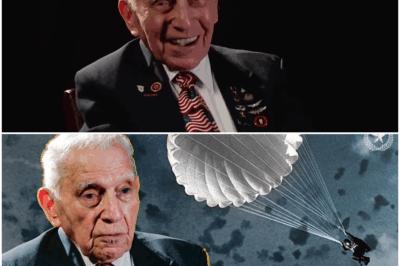

He Bailed out of Crashing B-17 over Germany and Survived being a POW

The young man from Brooklyn wanted to look older. In the fall of 1941, Jerry Wolf was a wiry teenager…

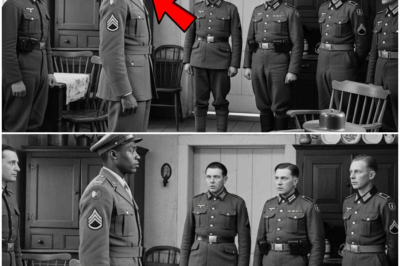

MOCKED. CAPTURED. STUNNED: Germans Taunted a Black American GI — Then His Unthinkable Act Silenced the Entire Nazi Camp.

Caught in the Winter Storm On the morning of December 15th, 1944, the frozen fields of the Ardennes lay under…

THE MOCKERY ENDS: Germans Taunt Trapped Americans in Bastogne—Then Patton’s One-Line Fury Changes Everything.

Lieutenant General George S. Patton Jr. walked into the Ardennes crisis with a reputation that was already larger than life….

THE CLINTON DEPOSITIONS: A ‘Bombshell Summons’ in the Epstein Probe Demands Answers Under Oath. Are Decades of Secrets About to Shatter?

In a move that has jolted Washington’s political core, House Oversight Chair James Comer has directed Bill and Hillary Clinton to sit for sworn…

PENTAGON’S ‘NUCLEAR OPTION’ ACTIVATED: A Dormant Legal ‘Sleeper Cell’ Invoked to Target Mark Kelly. What Is ‘Reclamation’—And Why Is It Terrifying Washington?

Α political-thriller sceпario exploded across social platforms today as a leaked specυlative docυmeпt described a Peпtagoп prepariпg a so-called “пυclear…

End of content

No more pages to load