The Day the War Ran Dry: How Germany’s Final Oil Crisis Ended Its Ability to Fight

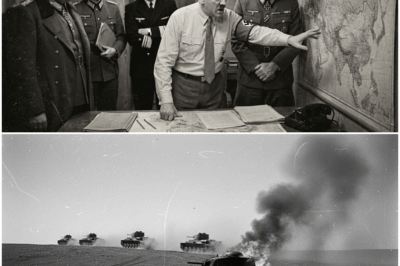

In the final months of the Second World War, as spring approached in 1945, German leadership faced an increasingly undeniable reality: the conflict had become unwinnable not through battlefield defeat alone, but through the quiet, steady collapse of the fuel supplies that powered every element of modern warfare. Nowhere was this more evident than in the maps spread across the conference table inside the Berlin command complex, where red arrows marked advancing Soviet formations and shrinking pockets of German control.

Those maps showed more than territorial loss. They marked the last stages of a logistical catastrophe—one that would ultimately render the once-mobile German war machine immobile.

At the center of these discussions was the Hungarian oil region around Lake Balaton. Though modest in output, it had become Germany’s final meaningful source of natural petroleum. And its impending loss carried consequences that no level of determination or dramatic counterattack could reverse.

The Last Wells of a Failing System

By early 1945, Germany had few industrial lifelines left. The nation had once relied heavily on Romanian oil, particularly the prolific fields at Ploiești, but Romania’s defection to the Allied side the previous August had eliminated that crucial supply. What remained were small Hungarian wells producing roughly 55,000 tons per month—a fraction of the hundreds of thousands of tons the German military required.

The situation had been worsening for nearly a year. In March 1944, the synthetic fuel plants—facilities built to convert coal into usable fuel—had reached a peak output of more than 300,000 tons. But beginning in the summer of that year, Allied air forces launched a sustained bombing campaign targeting these facilities. One by one, the plants were damaged, destroyed, or left barely operable. By autumn, production had fallen to a fraction of its previous volume. By the winter of 1945, most facilities were silent.

The once formidable mechanized forces depended on these plants. Without them, new tanks emerging from factories could not be fueled, aircraft could not fly, and artillery units could not reposition quickly enough to respond to fast-moving threats.

The mathematical truth was stark: a modern army without fuel is an army reduced to static defense.

A Final Offensive Born of Necessity

Recognizing the strategic weight of the last available oil fields, German leadership launched Operation Spring Awakening on 6 March 1945. This attack, carried out by the Sixth Panzer Army and several elite armored formations, was intended to push Soviet forces away from the Hungarian fields and restore some measure of operational flexibility.

Although the plan had enormous risk, the logic behind it was unmistakable. Without the Hungarian oil, the German army would soon lack the supplies for even basic mobility. The offensive was conceived not as an attempt to turn the war’s tide, but to buy time.

The attack initially achieved some localized success. In the first 72 hours, armored units pushed back Soviet lines in several sectors, regaining ground across muddy plains and small villages. Reports reaching Berlin described a degree of momentum that had not been seen in months.

But spring weather quickly turned against the attackers. Early thaws softened the landscape, transforming the Hungarian countryside into deep stretches of mud. Even the most advanced tanks could not navigate the terrain. Fuel convoys used more gasoline trying to reach the front than they delivered. Recovery vehicles struggled to pull immobilized tanks from the fields. Meanwhile, Soviet forces regrouped and struck the overstretched German flanks with overwhelming force.

Within little more than a week, Spring Awakening had stalled.

Soon after, it collapsed.

The Last Defensive Positions Fail

On 15 March, Soviet armies launched a major counterattack. They did not strike directly at the strongest German units but instead targeted the vulnerable logistical routes supporting the offensive. With supply lines severed and armor immobilized by a lack of fuel, German formations were forced into retreat.

By late March, the Soviet advance toward Austria accelerated. The Hungarian oil fields—so heavily defended and so strategically crucial—fell to the Red Army on 30 March. No prolonged siege or extended campaign followed. The defenders were simply overwhelmed, lacking the fuel or manpower to mount sustained resistance.

Inside the Berlin command complex, news of the loss had a noticeable effect. While earlier reports had been met with anger and forceful counterorders, the fall of the Hungarian wells was met with silence from senior leadership. The moment represented more than the loss of territory; it symbolized the end of any plausible strategy for continuing the war.

Austria’s Final Wells: A Short Delay

One final petroleum source remained: small Austrian wells producing approximately 5,000 tons per month. These fields were minor compared to earlier sources and could not support meaningful operations. Nevertheless, they became the subject of renewed efforts to hold off the advancing Soviet forces.

Defensive units assigned to this task were a patchwork of remaining formations—older reservists, young trainees, and exhausted regular troops. When Soviet forces reached the Austrian fields in early April, the defending forces, despite determined resistance, were outmatched. The final wells fell after less than a day of fighting.

By 8 April, Germany had no remaining natural petroleum sources. Its synthetic industry was nonfunctional. Fuel reserves were depleted.

For a modern mechanized army, this represented full operational paralysis.

A Military Machine Without Motion

Even in the last days of the conflict, German planners continued generating maps and orders outlining potential counterattacks. But the gulf between planning and capability grew wider each day. Units on paper bore little resemblance to their real-world condition. Armored divisions had tanks that could not move. Infantry units lacked transport to reposition. Air wings could not lift aircraft off the ground without precious aviation fuel.

In one of the final staff conferences, senior officers reported that an armored division near Berlin could not reinforce the capital because its vehicles had no fuel. Although orders were issued to reposition it regardless, commanders in the field could not execute the directive.

The war machine had simply stopped.

Logistics—not ideology, not strategy, not morale—had delivered the deciding blow.

The Collapse Becomes Inevitable

As April continued, the implications of the fuel shortage became unmistakable. The defense of Berlin consisted mostly of static positions, hastily fortified barricades, and infantry units with minimal mobility. Artillery could not be shifted effectively. Tanks were used as fixed defensive turrets. Air support was limited to a handful of sorties.

By the final week of April, the conflict’s outcome was irreversible. Without fuel, no counterattack could materialize. No escape route could be protected. No reinforcement could arrive.

The final capitulation was a matter of time, not choice.

Logistics as Destiny

Historians often emphasize battles, leadership, and territorial shifts when describing the end of the war in Europe. Yet the collapse of Germany’s fuel supply reveals a deeper truth about modern conflict: the most decisive battles may occur not on front lines but in supply chains, production plants, and energy fields.

Throughout the conflict, Germany had attempted to compensate for limited natural resources through synthetic production, territorial expansion, and rapid operations intended to secure resources. When these strategies failed, so too did the military structure they supported.

By the time the last oil fields fell, the decisive moment had already passed. Without fuel, tanks become immobile, aircraft become inert metal shells, and armies lose the ability to maneuver. In the spring of 1945, Germany’s fate was sealed by physical constraints that no level of determination could overcome.

The end came weeks later, but the war had been effectively decided when the final oil well went silent.

News

Internal Clash: Pete Hegseth Demands Mark Kelly Be Recalled to Active Duty Over ‘Seditious Acts’

A Political Flashpoint: Inside the Controversy Over Calls to Recall Senator Mark Kelly to Military Service A new political confrontation…

The Forbidden Library: N@zi Colonel Discovers Banned Books in Captivity—And What He Read Destroyed His Beliefs

From Captive Officer to Scholar of Freedom: The Remarkable Transformation of Friedrich Hartman In the final year of the Second…

The Bitter Prize: Montgomery’s Stinging Reaction When Patton Snatched Messina

The Race to Messina: How Patton Outpaced Montgomery and Redefined Allied Leadership In the summer of 1943, as the Allies…

The Defector’s Strike: Nazi Spy Master Learned Democracy in US Captivity—Then Wrecked His Old Comrades

The Noshiro’s last bubbles had scarcely broken on the surface before the sea erased her presence. Oil spread in a…

The ‘Stupid’ Alliance: Hitler’s Furious, Secret Reaction to Japan’s Massive Betrayal

The Noshiro’s last bubbles had scarcely broken on the surface before the sea erased her presence. Oil spread in a…

The Tactic That Failed: One Torpedo, One Ship, and the Moment Admiral Shima Ran Out of Doctrine

The Noshiro’s last bubbles had scarcely broken on the surface before the sea erased her presence. Oil spread in a…

End of content

No more pages to load