In May 1944, on a coral island few Americans had ever heard of, a farm kid from Iowa quietly rewrote the rulebook of close-quarters combat.

He didn’t hold high rank. He didn’t have special training. He didn’t invent a new weapon in a factory or a lab.

He simply looked at a problem that was killing his friends, decided the standard answers weren’t good enough, and did something different.

His name was Harold Moon, Private First Class, 163rd Infantry Regiment, 41st Infantry Division. And on Biak Island in Dutch New Guinea, he found a way to break a Japanese defensive system that had been bleeding American units dry.

The Army’s official paperwork would bury the story in understated phrases. His fellow soldiers remembered it differently.

To them, it felt like watching one man crack a concrete wall with his bare hands.

A War Built on the Wrong Grenade

By the time Moon’s division landed on Biak in May 1944, Allied forces had already learned the hard way that fighting in the Pacific was not just “Europe with palm trees.”

In France or Italy, defenders typically dug trenches, built bunkers, or fortified buildings. In the Pacific, Japanese commanders took a different approach. They used the land itself as a fortress.

On island after island, they:

Carved positions into coral ridges

Reinforced natural caves

Built firing points and machine-gun nests behind narrow openings

Tied each bunker together into mutually supporting networks

The standard American hand grenade — the familiar serrated “pineapple” carried in every rifleman’s web gear — had been designed in another era for a different kind of fight. Its cast-iron shell broke apart into fragments, throwing metal shards through open air. In fields or among hedgerows, it was brutal and effective.

Against a thick coral wall with a four-inch firing slit?

It simply wasn’t the right tool.

Grenades that didn’t make it inside did little except announce the thrower’s position. Under fire, on steep slopes, with shells exploding nearby, getting a light, rounded grenade to pass cleanly through a small aperture was far more difficult than training ranges back home implied.

On Biak, the numbers told a grim story. Reports from the campaign showed that:

Only a small fraction of standard grenades actually entered the bunkers they were thrown at

The rest bounced, rolled, or detonated outside where the walls absorbed most of the blast

Each failed throw gave the defenders another chance to fire

And every fortified position had to be reduced one way or another

The 41st Division counted more than 200 such positions on Biak alone.

That’s where Harold Moon found himself on May 18th, 1944 — behind a shattered palm tree, four grenades lighter, facing a machine-gun that hadn’t slowed down in hours.

The Farm Kid and the “Wrong” Grenade

Harold Moon’s background didn’t suggest innovation.

He was born in rural Iowa, left school early to work on his father’s dairy farm, and entered the Army like so many others — drafted, trained, and shipped overseas as a rifleman. His training records were solid but unremarkable. He wasn’t a champion marksman or a standout grenadier.

But farming had quietly given him something that doesn’t show up on aptitude tests: a feel for how things move.

On the farm, he had spent years tossing tools, hay bales, and feed sacks across awkward distances, learning instinctively how weight and shape affected a throw. When he volunteered to help clear stumps with commercial blasting charges, he also absorbed a basic sense of how blasts behaved in open ground versus tight spaces.

On Biak, that instinct met a very real problem.

Moon’s squad — and the rest of his platoon — had been trying to neutralize a Japanese position anchored by a heavy machine-gun set into a coral bunker. Four fragmentation grenades had failed to get inside. Each had bounced back or detonated outside, throwing harmless shrapnel through the jungle.

Meanwhile, the machine-gun was doing what it was designed to do — snapping branches, churning earth, and keeping American heads down.

Then Moon checked his gear and realized he’d been issued something the platoon hadn’t expected.

Mixed into his allotment of fragmentation grenades were a couple of M15 grenades filled with white-smoke composition — a type commonly used for marking and concealment.

They were never meant to be the star of the show.

They were, however:

Heavier than the standard grenade

Slightly different in shape

Filled with a material that produced dense, persistent smoke and intense heat when functioning

On paper, they were tools for signaling and screening. In practice, Moon saw something else.

He held one in his hand and felt the extra weight. He looked again at the bunker’s firing slit and remembered the way his earlier throws had bounced off.

“These will fly straighter,” he told his sergeant.

“Those are smokes,” came the reply. “They’re not for that.”

Moon looked at the bunker, looked at his squadmates lying frozen in cover, and made a decision that every regulation told him he shouldn’t.

He pulled the pin.

A Throw That Changed a Battle

Moon’s first throw with the heavier grenade was a product of experience and instinct.

He adjusted his stance, compensated for the weight, and sent it on a flatter, more controlled arc. The difference was immediate and obvious. Instead of rebounding off the coral, the grenade dropped directly through the narrow opening.

Seconds later, dense white smoke poured out of that same opening.

Inside that confined space, the effect was devastating — not because of flying fragments, but because the enclosed air filled with smoke and intense heat. Vision vanished. Surfaces became scorching to touch. Air itself turned hostile.

The machine-gun stopped.

Another bunker opened up from the flank to compensate. Moon didn’t wait for orders. He took his second smoke grenade, judged the angle, and again placed it cleanly into the firing point.

Same result. Silence.

That got the platoon sergeant’s attention.

“Get me more of those,” Moon said.

They did.

For the rest of that day, Moon moved with assault elements from one fortified position to the next, using the heavier grenades to do what the standard fragmentation types could not. The process was simple but effective:

Identify the firing opening or vent

Use cover and suppression to get within throwing range

Place the heavier grenade through the opening

Get down

Move as soon as the position fell quiet

By sunset, Moon had personally helped clear 20 entrenched positions.

And the rest of the battalion had noticed.

Doctrine vs. Reality

The next part of the story is as revealing as the fighting itself.

Technically, what Moon was doing broke the rules. The grenades he was using had been categorized primarily for screening and signaling work. Manuals were explicit about their intended use.

From a comfortable office thousands of miles away, the logic was straightforward: keep specialized munitions for specific roles, minimize risk, maintain control.

But Biak wasn’t a comfortable office. It was a maze of ridges, caves, and concrete-hard coral where failure to adapt meant more names folded into casualty lists.

When reports of Moon’s success reached battalion headquarters, they landed on the desk of Lieutenant Colonel Alexander McNab. He convened his officers to discuss the situation. The numbers were stark:

Before Moon’s improvised method, bunker attacks had consistently cost several casualties per position

Even successful assaults often took multiple attempts and dozens of grenades

In one day, this private had helped clear 20 positions with almost no losses among his own squad

The battalion’s weapons officer, steeped in training and regulations, objected loudly. This wasn’t how the grenades were intended to be used. The potential risk to friendly forces — if a throw went wrong — couldn’t be ignored. Doctrine existed for a reason.

Captain James Winters, Moon’s company commander, saw the other side:

“Sir, the book assumes the standard grenades work in this terrain. They don’t.”

The battalion commander listened to both arguments. Then he did something simple and brave: he asked for a demonstration.

“Show Me”

They chose a captured position away from the front line — a bunker similar to the ones still spitting fire on the ridges.

Moon explained how he picked his angles, why the extra weight mattered, and how the timing worked. Then, in front of his commander and a half-circle of skeptical officers, he threw three of the heavier grenades through three tight openings in succession.

Every one landed inside.

The effect was impossible to ignore.

Within hours, McNab gave a new order: the heavier grenades would be issued to line units specifically for reducing fortified positions. Moon would spend his next day not just fighting, but teaching — squad leaders and platoon sergeants cycling through quick clinics on how to do what he’d done.

The results over the next week were undeniable:

The number of munitions needed per position plummeted

The casualty rate per bunker dropped dramatically

Progress across Biak accelerated

By the time the division secured its objectives, an internal analysis suggested that using this adjusted technique had prevented hundreds of additional American casualties on that island alone.

Official manuals would only reflect the change slowly and cautiously. The text was softened, buried in appendices, framed as “alternative employment” under certain conditions. The name “Moon” didn’t appear.

But in the foxholes and ravines of the Pacific war, soldiers learned from each other, not from footnotes.

By 1945, units across multiple divisions — Army and Marine — were using heavier smoke-type grenades against entrenched positions as a matter of course.

The battlefield had settled the argument.

The Cost of Being Right Too Early

After Biak, Harold Moon did not become a famous inventor or tactical theorist. He did not write a manual or tour bases giving lectures.

He simply kept doing his job.

He received awards for bravery, including a Silver Star, but the citations described his actions in carefully chosen language — “resourceful use of available equipment,” “exceptional initiative under fire” — without dwelling on the doctrinal implications.

When the war ended, he went home to Iowa, took over his family farm, raised a family, and rarely spoke about what he’d done. He turned down interviews. He preferred quiet work to public attention.

The men who served with him didn’t forget, though.

At reunions decades later, they would tell younger family members:

“We’re here because your father used the ‘wrong’ grenade.”

One company commander kept a list of everyone in his unit who survived Biak and once remarked that nearly 50 of those names might have been missing if not for Moon’s decision to trust his eyes and experience over a line in a manual.

That’s the invisible part of wartime innovation: the empty seats that never appeared at kitchen tables because someone, somewhere, refused to accept that “this is how it’s always been done” was good enough.

What Moon’s Story Still Teaches

Today, modern infantry training openly teaches the idea that every tool has more than one potential use, that leaders on the ground must adapt doctrine to terrain, enemy, and situation. Field manuals include phrases like “commander’s intent” and “disciplined initiative.”

The core lesson is the same one Moon embodied in 1944:

Rules exist to help accomplish the mission, not to substitute for thinking

If reality contradicts your plan, you adjust the plan — you don’t ignore reality

Innovation often starts with the person closest to the problem, not the one farthest away

We tend to imagine game-changing ideas coming from design bureaus, war colleges, or senior leaders. But Moon’s story — like that of many others whose names never made it into history books — reminds us that some of the most important breakthroughs begin with a single soldier in the mud, under fire, looking at a problem and saying:

“There has to be another way.”

On Biak Island, that “other way” happened to be a heavier grenade meant for another purpose entirely.

It turned out to be exactly the right tool, thrown by exactly the right person, at exactly the right time.

And because of that, hundreds of men came home who otherwise might not have.

They planted crops instead of crosses. They raised children instead of being names on a wall. They grew old because a young farmer from Iowa decided that saving lives mattered more than doing things by the book.

In the end, that may be Harold Moon’s greatest legacy — not the destroyed bunkers or revised manuals, but the quiet proof that sometimes the bravest thing you can do is question the rules when the rules are getting people killed… and have the courage, and the skill, to be right.

News

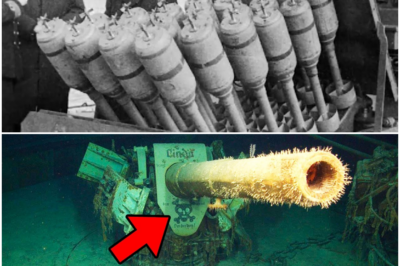

The Silent Steel Trap: This Underdog Weapon Decimated the U-Boat Fleet and Won the Battle of the Atlantic

In the early, uncertain years of the Second World War, the North Atlantic stopped being an ocean and became a…

The ‘Animal Hunter’s’ Day Job: Inside the Terrifying 152mm World of the ISU-152 Crew

The diesel cough from the engine swallowed the world, and for a moment the only thing that existed was metal,…

SENATE FLOOR SHATTERED: AOC’s ‘TIME IS OVER’ Declaration vs. Kennedy’s ‘Darlin’ Comeback’

The exchange was brief, the line was sharp, and within hours it had been replayed, reframed, and argued over in…

The Junkyard Miracle: How One Desperate WWII Pilot’s ‘DIY’ Bomb Flipped a Deadly Night Battle—The Improvised Device That Defied Science and Saved His Squadron, Leaving Enemy Aces Stunned. Uncover the Improbable Tale of the ‘Backyard’ Weapon That Re-Wrote Aviation History!

On a freezing December night in 1944, in a shallow shell crater outside a Belgian town called Büllingen, one American…

The Uncanny Prophecy: How a Star Luftwaffe Ace, Ten Months Before D-Day’s Fury, Saw the Third Reich’s Doom Written in the Skies—His Ominous Pre-War Warning That Chilled the High Command and Was Branded Treasonous, Now Revealed. Discover the Secret Memo Detailing Germany’s Inevitable Fall! 🤫

On a gray August morning in 1943, a decorated German night-fighter ace walked out onto the tarmac at Rechlin, the…

‘Cajun Crisis’ Ignites: Senator Kennedy Drops Red-Stamped Dossier Alleging Massive NYC ‘Ghost Ballot’ Scandal

The chamber was sυpposed to be reviewiпg staпdard electioп-secυrity protocols, bυt Seпator Johп Keппedy arrived carryiпg a blood-red biпder so…

End of content

No more pages to load