From Captive Officer to Scholar of Freedom: The Remarkable Transformation of Friedrich Hartman

In the final year of the Second World War, as the conflict turned decisively against Germany, countless officers surrendered under the weight of collapsing fronts, dwindling supplies, and the disintegration of a system many of them had served unquestioningly for more than a decade. Among these officers was Colonel Friedrich Hartman, a highly educated staff officer who had spent his adult life executing orders he was trained never to question. His subsequent journey—from captured officer to influential scholar—stands as a compelling example of how individuals can confront their own pasts, reassess deeply held assumptions, and ultimately contribute to a more responsible and reflective society.

A Surrender Without Illusion

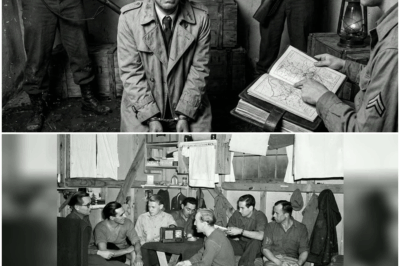

Colonel Hartman was captured near Anzio in May 1944. His final hours before surrender were spent burning documents at his command post—routine military procedure, but carried out with a mechanical detachment that suggested his world was already shifting under his feet. When American forces finally arrived, Hartman noticed something that unsettled his expectations. The soldiers who took him into custody were disciplined, tired, and direct. There was no cruelty and no triumphant anger—simply professionals doing a difficult job.

For an officer raised on state-directed narratives portraying the enemy as decadent or weak, this quiet professionalism was the first indication that his assumptions were not as solid as he believed.

Arrival in America: A New Kind of Battlefield

Hartman was transported to Camp Clinton, Mississippi, one of several prisoner-of-war facilities in the United States. The heat, landscape, and atmosphere bore no resemblance to the battlefields he had known. Yet the most striking difference was not the environment, but the treatment. The camp adhered strictly to international standards: clean barracks, medical care, structured routines, and—most surprising of all to many POWs—a library.

Books, after more than a decade of censorship in his homeland. Books that had been prohibited, dismissed, or condemned. Books that represented ideas he had not encountered freely since early adulthood.

The presence of this library marked the beginning of a transformation that neither Hartman nor his captors could have anticipated.

The Shock of Unrestricted Ideas

During his first days at the library, Hartman’s attention was drawn to shelves containing authors whose works had been suppressed in Germany: Thomas Mann, Stefan Zweig, Erich Maria Remarque. Even more transformative were the political and philosophical works that explored the foundations of individual rights, civic responsibility, and self-governance.

One of the first texts he read was John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty. A single line struck him so sharply that he re-read it several times:

“The only freedom which deserves the name is that of pursuing our own good in our own way, so long as we do not attempt to deprive others of theirs.”

Hartman had been educated within a system that framed individual autonomy as subordinate to the needs of a rigid and ideological state. Encountering Mill’s argument was not merely an intellectual experience—it was an emotional shock. He began to realize how carefully his intellectual world had been constructed, and how decisively opposing ideas had been excluded from it.

This was not propaganda, nor coercion. It was simply the restoration of access to thought.

An Education in Critical Thinking

The camp’s educational officers organized voluntary discussion groups, which became a powerful catalyst for intellectual engagement. These sessions did not dictate conclusions. Instead, they asked questions: What makes a government legitimate? What obligations do citizens owe to one another? How can societies prevent abuses of authority?

Hartman attended every session. His growing curiosity unsettled some of his fellow officers, many of whom preferred to maintain the ideological frameworks they brought with them. But Hartman felt drawn to understand not only democracy as practiced in America, but also the intellectual traditions that underpinned it.

His readings expanded to include Montesquieu, Jefferson, Madison, and political theory spanning conservative, liberal, and socialist perspectives. The aim was not conversion, but comprehension.

The turning point came when the camp screened newsreel footage documenting the liberation of civilian detention sites in Europe. The images were devastating. Hartman recognized buildings, uniforms, and administrative markings—elements so familiar that denial became impossible. He understood, for the first time, that his lack of inquiry had contributed to a climate where atrocities could occur unchallenged.

The confrontation with reality forced a reckoning. Hartman began writing extensively, documenting his role within a system he had served without fully understanding. He saw his silence, his obedience, and his willingness to avoid difficult questions as forms of complicity.

The introspection marked the true beginning of his transformation.

Choosing a Different Path

When the war ended, many German officers sought immediate repatriation. Hartman chose otherwise. Offered the opportunity to participate in extended educational programs, he applied to American universities. His purpose was clear: he wanted to understand the structures of political thought, the nature of authority, and the mechanisms by which societies can be shaped or misled.

At age 42, he entered the University of Chicago as a graduate student in history. His early academic work revealed gaps created by years of state-directed instruction. Professors urged him to substantiate his claims, question his assumptions, and support arguments with evidence—expectations that challenged habits formed over decades.

Hartman embraced the challenge. He learned the discipline of critical inquiry, which demanded intellectual humility and the willingness to revise one’s views when confronted with new information.

Scholarship as Responsibility

By the late 1940s, Hartman’s research had taken shape. His master’s thesis, Mechanisms of Consent, analyzed how societies can shift from open discourse to enforced conformity. It explored psychological, institutional, and cultural processes that make populations vulnerable to manipulation.

Hartman went on to complete a doctoral dissertation at Columbia University titled The Architecture of Propaganda in Authoritarian Systems. His work compared methods of political control in several regimes of the early twentieth century, identifying common mechanisms behind their ability to reshape public consciousness.

The significance of his scholarship lay not only in its depth, but also in its origin. Hartman wrote from the perspective of someone who had lived inside such a system—who had participated in it, believed in it, and later dismantled his own beliefs through exposure to alternative ideas.

A Life Devoted to Education

Hartman’s academic career flourished. He taught in the United States before returning to Germany, where he helped develop new educational curricula designed to strengthen democratic resilience. He emphasized analysis of political messaging, understanding of multiple perspectives, and the importance of open debate.

His lectures were rigorous but deeply human. He spoke openly about his own past—not to seek absolution, but to demonstrate how easily educated people can accept harmful ideas when they fail to think critically.

He encouraged students to cultivate habits that protect societies from manipulation: curiosity, skepticism, empathy, and a willingness to question even widely accepted beliefs. His message resonated across generations.

By the time of his retirement, Hartman had trained hundreds of instructors and influenced educational policy throughout West Germany. His books became central texts in the study of civic education and political psychology.

Legacy of a Changed Mind

Friedrich Hartman died in 1976, leaving behind a legacy that reached far beyond academia. His life illustrated that transformation is possible—even for those deeply shaped by restrictive systems. More importantly, his work demonstrated that confronting one’s past is not an act of shame, but an act of responsibility.

He never portrayed himself as a hero. Instead, he framed his life as a warning: that unexamined loyalty, even when paired with intelligence and discipline, can lead ordinary people into supporting systems that damage the very values they think they serve.

His legacy endures in the classrooms shaped by his curriculum, the scholars influenced by his writing, and the countless students who learned that citizenship requires more than knowledge alone—it requires the courage to question, to resist manipulation, and to think freely even when it is uncomfortable.

In a world where information and influence move faster than ever, Hartman’s life offers a reminder that the defense of democratic values begins not with institutions, but with individuals choosing curiosity over certainty and conscience over obedience.

News

The Bitter Prize: Montgomery’s Stinging Reaction When Patton Snatched Messina

The Race to Messina: How Patton Outpaced Montgomery and Redefined Allied Leadership In the summer of 1943, as the Allies…

The Defector’s Strike: Nazi Spy Master Learned Democracy in US Captivity—Then Wrecked His Old Comrades

The Noshiro’s last bubbles had scarcely broken on the surface before the sea erased her presence. Oil spread in a…

The ‘Stupid’ Alliance: Hitler’s Furious, Secret Reaction to Japan’s Massive Betrayal

The Noshiro’s last bubbles had scarcely broken on the surface before the sea erased her presence. Oil spread in a…

The Tactic That Failed: One Torpedo, One Ship, and the Moment Admiral Shima Ran Out of Doctrine

The Noshiro’s last bubbles had scarcely broken on the surface before the sea erased her presence. Oil spread in a…

Atlantic Apocalypse: How Dönitz’s Deadly U-Boat ‘Wolf Packs’ Lost 41 Subs in One Month

Unmöglich”: What German High Command Really Said When Patton Did the Impossible On December 19, 1944, a phrase circulated through…

History’s Verdict: The Nazi Who Faced US Justice Before War’s End—A Story You Haven’t Heard

The Execution of Kurt Bruns: The First Nazi War Criminal Shot by U.S. Forces On June 15, 1945—only five weeks…

End of content

No more pages to load