On a muddy patch of ground outside Remagen in March 1945, two worlds that had been taught to despise one another met inside the barbed wire of a German prisoner-of-war camp.

On one side of the fence were more than 800 German women—former communications officers, nurses, clerks, auxiliaries—captured during the collapse of Germany’s western defenses. On the other side, stepping down from a line of olive-drab trucks that afternoon, were the new guards: thirty-two Black American soldiers of the U.S. 361st Infantry Regiment.

For the women, it was a shock so deep they could almost feel their sense of reality tremble.

They had seen American tanks and white American soldiers briefly, in glimpses through ruined streets or from the windows of transport trucks. But Black Americans—especially as disciplined, capable soldiers and officers—belonged, in their minds, to propaganda posters and distorted newsreels. They were caricatures, not people.

Within weeks, that illusion would be gone.

The Arrival of the 361st

The camp lay three kilometers southeast of Remagen, hastily constructed to house female prisoners captured in the final battles along the Rhine. Wooden barracks leaned slightly in the mud; barbed wire lines crisscrossed the perimeter. Major Robert Stevens, a white American officer from Ohio, had been overseeing the facility with a rotating guard of white MPs.

On March 15th, the routine changed.

The convoy that rolled through the gates was commanded by Captain James Washington, a 28-year-old company commander whose path had taken him from segregated neighborhoods in the United States to the beaches of Normandy and across a battered continent. Behind him, his men climbed from the trucks, their uniforms neat despite the long ride, weapons carried safely at the ready, eyes alert.

From behind the barracks windows, German women watched in absolute silence.

Helga Schmidt, a former communications officer from Munich with a university degree in literature, found herself unable to reconcile what she saw with what she had been told. These men did not stumble or shout or swagger. They moved like the professional soldiers she herself had once helped direct over field telephones: organized, efficient, controlled.

Other women—nurses, radio operators, clerks—felt the same jarring dissonance. Years of carefully crafted messages about “racial hierarchies” collided with the calm presence of Black American officers and NCOs who clearly knew exactly what they were doing.

First Contact: Rations and Records

The camp itself did not change overnight. The women still slept in crowded bunks, still lined up for food at set times, still answered roll call three times a day. But the rhythm of life—who gave orders, who kept the lists, who fixed the broken things—began to look very different.

Sergeant Marcus Johnson, a former factory worker from Detroit, was assigned to supervise evening meal distribution. Clipboard in hand, he took up his post near the serving window. His job was simple on paper: ensure every prisoner received her ration, and record it. In practice, it was a front-row position in the first sustained interaction many of these women had ever had with someone they had been taught to see as categorically “other.”

One prisoner, a former radio operator from Dresden, approached the line with shaking hands. She expected shouting, or worse. Instead, Johnson glanced up, met her eyes briefly, and spoke in careful German:

“Guten Abend. Bitte, Ihre Nummer.”

Good evening. Please, your prisoner number.

He had learned the phrases deliberately, out of respect for good procedure and a desire to be understood. His handwriting on the record sheet was precise. His tone was neutral, even polite. He was clearly literate, clearly attentive, clearly in charge.

The moment was small, over in seconds. But for Anna Braun, and for dozens of women in line behind her, it lodged in memory like a stone in still water. The ripples would spread slowly.

Breaking the Script: Library, Workshop, Infirmary

Captain Washington had not brought his men to the camp to teach social lessons. Their primary duty was security. But he understood, from experience, that the way tasks were delegated could shape perceptions as powerfully as any speech.

He designed a rotation that would put his men in every corner of camp life. Not just on the towers or the gate, but in the places where skills were most visible.

Corporal David Thompson, a college student from Chicago before the war, was put in charge of the small camp library and educational programs. The German prisoners quickly learned that he spoke fluent German. They were slower to realize just how much else he knew.

When Helga Schmidt engaged him in conversation about Goethe, she expected polite bafflement. Instead, she found herself discussing Faust with someone who had read it in German and could quote passages from memory. Their discussion wandered from Sturm und Drang literature to the American Transcendentalists, to the differences between German Romanticism and the Harlem Renaissance.

For a woman whose worldview had been shaped by a belief in European intellectual superiority, it was a quietly shattering experience.

In the camp workshop, similar moments unfolded. When a pump in the water system failed, work details stalled. The German women knew enough about machinery to understand that repairs were non-trivial. Yet Private Tommy Williams, a 20-year-old from rural Alabama, disassembled the pump, improvised a replacement part from scavenged metal, and had it functioning again within hours.

He explained what he was doing as he went—not in perfect German, but in enough words and gestures for the watching women to follow the logic. It was the language of practical intelligence.

In the infirmary, Corporal Robert Jackson’s presence was even more impactful. Jackson had studied medicine before being drafted and now assisted the camp medic in treating illnesses and injuries.

When a prisoner, Greta Müller, fell seriously ill with a lung infection, Jackson monitored her through the night, adjusting her blankets, checking her breathing, administering medicine under the medic’s supervision. He did not rush her, did not snap at her questions, did not treat her as less deserving of care because she wore a different uniform.

Greta had been told that Black people were less rational, less capable, less disciplined. Jackson’s steady hands and quiet focus forced her to confront the absurdity of those beliefs.

Complex Stories on Both Sides of the Wire

As days turned into weeks, conversations deepened.

Many of the German women had served as clerks or radio operators. They were educated. They had grown up in cities, read newspapers, attended theaters. Now they found themselves speaking—sometimes hesitantly, sometimes with surprising ease—with men from Detroit, Birmingham, Chicago, and rural Mississippi.

They learned that these American soldiers had grown up in a country that combined democratic ideals with harsh segregation. That some had been denied jobs or promotions because of the color of their skin. That “separate but equal” was a legal phrase that rarely matched reality.

Sergeant Johnson told one prisoner how he had been turned away from factories that later desperately needed workers, solely because of his race. Only when the war came did his country decide it wanted him—in a uniform, in danger.

Corporal Thompson spoke of college lectures interrupted by news of Pearl Harbor, of professors debating democracy and hypocrisy in the same breath. Private Williams spoke quietly about grandparents born into slavery, parents who sharecropped land they did not own, and his own determination that his children would not live the same way.

For the German women, who were still absorbing emerging reports of concentration camps and mass killings, the moral landscape grew more complicated with each new story.

They were prisoners of a nation that had unleashed a war of aggression and genocide. But the men guarding them, whose professional behavior and compassion they now experienced daily, were not exempt from injustice at home.

A Turning Point: News from Other Camps

In early April, news filtered in about the liberation of Buchenwald, Bergen-Belsen, and other camps. Official announcements painted pictures that many Germans had never been allowed to see: emaciated survivors, mass graves, institutionalized cruelty.

Some of the women in the Remagen camp refused to believe the reports. Others suspected exaggeration. But a growing number—especially those who had seen enough of the regime’s darker corners to harbor private doubts—began to accept that the stories might be true.

At the same time, they looked at their own situation: being treated humanely by soldiers whom their newspapers had depicted as brutal savages. The contrast could not be ignored.

In conversations by bunks and in exercise yards, women like Ingrid Weber and Dr. Elisabeth Hoffmann (a former university professor captured while serving as a medical auxiliary) began to articulate uncomfortable truths: if the ideology had lied to them about Black people, what else had it lied about?

It was not an overnight conversion. Old habits of mind die slowly. But in small exchanges—over bandages, books, broken pumps, and ration lines—the foundation under racist assumptions eroded.

Helga, who had flinched at the first sight of Black guards, found herself correcting newer arrivals who repeated old propaganda. “You have not seen how they behave,” she would say. “I have.”

Beyond the Wire: Ripples That Lasted

When Germany formally surrendered in May 1945, the camp did not vanish instantly. There were procedures, paperwork, and transport schedules. Prisoners were interviewed by Allied officers. Many were asked about their treatment.

Again and again, German women described their surprise at the professionalism and humanity of their Black American guards.

Captain Washington, writing his final reports, noted the shift he had observed: initial fear and hostility slowly replaced by respect, and in some cases, genuine appreciation. His documentation didn’t just list disciplinary incidents or food statistics. It recorded anecdotes about conversations, repairs, late-night medical care.

Those reports would later feed into broader U.S. military discussions about integration. They offered concrete evidence that Black soldiers, given opportunity and authority, could perform at the highest levels of responsibility—even in the delicate context of prisoner management.

The German women went home, often to towns that had seen little of this kind of contact. They carried with them stories that few neighbors wanted to hear at first. It was easier to talk about hardships, bombings, and losses than about rethinking racial hierarchies.

Yet some persisted.

Greta, once recovered, spoke openly about Corporal Jackson’s skill and kindness. Anna Braun took up community work and quietly advocated for racial tolerance. Dr. Hoffmann returned to academic life and wrote about race, prejudice, and democracy, influenced heavily by what she had seen in that camp.

On the other side of the Atlantic, the men of the 361st returned to a United States that still segregated schools, restricted voting rights, and limited where they could live. They fought new battles—for fair housing, equal treatment in the workplace, recognition of their service. Some, like Thompson, documented their experiences in journals and letters that would later help historians reconstruct these quiet but powerful episodes.

Correspondence continued between a few former prisoners and guards. Letters crossed the ocean, carrying updates on children, job changes, and slow social shifts.

Why This Story Matters

The scene at Remagen in March 1945 could easily disappear into the larger sweep of history—a minor episode in a war dominated by huge offensives, famous generals, and dramatic liberation photographs.

But stories like this one matter because they reveal how change really takes root.

No law was passed inside that camp. No treaty was signed. No grand speech was given. Instead, thirty-two Black American soldiers showed up, did their jobs with competence and dignity, and treated the people in their charge as human beings—even though those people came from a nation that had denied their humanity.

The German women, raised under a regime that ranked human beings by supposed racial worth, encountered daily evidence that their categories made no sense. They watched a pump get fixed, a novel discussed, an infection treated, a ration line organized—and with each observation, the gap between propaganda and reality widened.

By the time they walked back through the gates toward whatever post-war Germany would become, many carried with them a different understanding of who was “civilized,” who was “inferior,” and what those words even meant.

The 361st Infantry Regiment might not appear prominently in most World War II textbooks. But its legacy, like that of so many segregated units, runs deeper than battle honors. It lies in changed minds: in the prisoners who returned home with new stories, in the officers who cited their performance in arguments for integration, in the quiet step-by-step erosion of a lie that had justified unspeakable things.

In that sense, the muddy camp outside Remagen was not just a holding facility. It was, for a brief moment, a place where the future was being negotiated—not at a conference table, but in the simple, stubborn practice of treating supposed enemies with decency, and letting the evidence speak for itself.

News

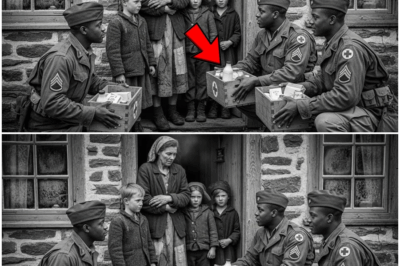

“I Thought They Were Devils,” German Woman Said After Black Soldiers Saved Her Starving Family

The chimneys in Oberkers had been cold for weeks. Snow lay heavy on the sagging roofs of the small German…

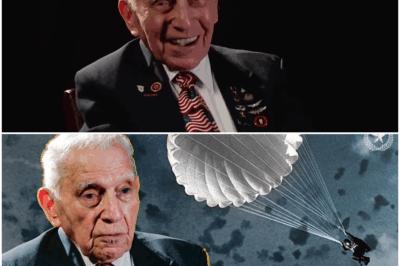

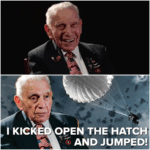

He Bailed out of Crashing B-17 over Germany and Survived being a POW

The young man from Brooklyn wanted to look older. In the fall of 1941, Jerry Wolf was a wiry teenager…

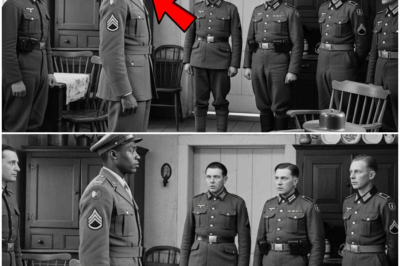

MOCKED. CAPTURED. STUNNED: Germans Taunted a Black American GI — Then His Unthinkable Act Silenced the Entire Nazi Camp.

Caught in the Winter Storm On the morning of December 15th, 1944, the frozen fields of the Ardennes lay under…

THE MOCKERY ENDS: Germans Taunt Trapped Americans in Bastogne—Then Patton’s One-Line Fury Changes Everything.

Lieutenant General George S. Patton Jr. walked into the Ardennes crisis with a reputation that was already larger than life….

THE GENERAL WHO WALKED: The Secret Sicily Incident That Almost Derailed WWII and Forced America’s Greatest Commander to Choose Honor Over Order.

The jeep rolled to a stop, and George S. Patton Jr. refused to go any farther. On the surface, it…

THE CLINTON DEPOSITIONS: A ‘Bombshell Summons’ in the Epstein Probe Demands Answers Under Oath. Are Decades of Secrets About to Shatter?

In a move that has jolted Washington’s political core, House Oversight Chair James Comer has directed Bill and Hillary Clinton to sit for sworn…

End of content

No more pages to load