On the afternoon of December 22, 1944, two men stared at the same map of Europe and reached very different conclusions.

In the town of Le Gläize, Belgium, SS Obergruppenführer Sepp Dietrich — commander of Germany’s vaunted Sixth SS Panzer Army — traced his finger across a bulge in the front line and smiled. His armored spearheads had smashed 60 kilometers into American positions in less than a week. Reports on his table spoke of retreating units, shattered divisions, and panicked radio calls.

“Americans are not soldiers,” he reportedly told his staff. “They are merchants playing at war. When real battle comes, they run.”

Seven hundred kilometers to the south, in Nancy, France, General George S. Patton studied the same bulge with an expression that could have frozen steel. His Third Army, facing east toward Germany, was already in motion for another offensive. Now, in a matter of hours, everything had changed.

At Eisenhower’s headquarters, the message was blunt:

The Germans have broken through in the Ardennes. Two US divisions have been shattered. A key town — Bastogne — is in danger of encirclement. The enemy is heading for the Meuse River, and beyond that, the port of Antwerp.

“How long will it take you to turn your army north?” Eisenhower asked.

Patton didn’t hesitate:

“Forty-eight hours.”

What followed was one of the most audacious maneuvers of the Second World War — and the moment when German arrogance collided with American adaptability.

Hitler’s Last Gamble

By late 1944, the German high command was trapped between two fronts.

In the east, Soviet forces were pushing inexorably toward Berlin.

In the west, American, British, and Allied armies had crossed France and driven to the borders of the Reich.

Hitler still believed one dramatic blow might split the Allied coalition, stall the advance, and perhaps force negotiations in the west. He summoned his planners and outlined a vision that stunned even his own staff.

The idea was simple on paper, impossible in practice:

Smash through the thinly manned American lines in the Ardennes

Cross the Meuse River

Capture Antwerp

Split British and American forces

Force the western Allies to reconsider their commitment

To do it, he gathered his last major reserves: 12 armored divisions, including elite formations like the 1st SS Panzer Division and Panzer Lehr. The code name given to the operation — Wacht am Rhein (“Watch on the Rhine”) — was deliberately misleading. It sounded defensive, not offensive.

But experienced officers saw the cracks immediately:

Fuel stocks were limited. Many armored units had enough for only a few days of intense fighting.

The German air arm had been weakened; Allied aircraft outnumbered them several to one.

The plan depended on perfect timing, captured fuel depots, compliant weather — and the assumption that American units would crack quickly.

That last assumption was the most dangerous.

The First Shock: December 16

Just before dawn on December 16, 1944, the quiet of the Ardennes was broken by a thunderous artillery barrage. Nearly 1,900 German guns opened fire along an 80-kilometer front.

In American foxholes, soldiers of the 99th, 106th, 28th, and other divisions were jolted awake by what many described as the heaviest shelling they had ever experienced. Trees exploded. Communications lines were cut. In the chaos that followed, German infantry and tanks rolled forward under cover of fog and snow.

On the northern flank, young soldiers of the 106th Infantry Division, barely two weeks in the line, were hit hard. Two of its regiments were encircled and, after days of fighting, forced to surrender. It would become the largest mass capitulation of US troops in Europe.

Reports from the front were grim:

Roads jammed with refugees and military traffic

German armored columns pushing west

Units falling back or losing contact

A massacre of American prisoners near Malmédy, which hardened attitudes on both sides

To Dietrich and others at German headquarters, the situation looked promising. The front had buckled. Terrain they had once crossed in triumph in 1940 now seemed to be opening for them again.

But other factors were already working against them: blown bridges, stubborn resistance at key road junctions like St. Vith and Bastogne, and fuel dumps denied to them by quick-thinking US engineers.

What Dietrich dismissed as “shopkeepers” were about to show a different side of American character.

Bastogne: The Thorn in the Bulge

As German columns pushed west, the road network of the Ardennes squeezed their advance into a few critical junctions. One of these was the small Belgian town of Bastogne.

If Bastogne fell and its roads remained in German hands, the Sixth SS Panzer Army and Fifth Panzer Army could continue pushing toward the Meuse. If it held, the advance would be constricted and vulnerable to counterattack.

Into this vital crossroads rode the 101st Airborne Division — veteran paratroopers who had fought in Normandy and Holland. Cut off and surrounded, low on ammunition and medical supplies, they dug in under their acting commander, Brigadier General Anthony McAuliffe.

When a German envoy delivered an ultimatum demanding surrender — supposedly to avoid “needless bloodshed” — McAuliffe’s written reply contained a single word:

“NUTS!”

To German officers, this was incomprehensible. To American soldiers, it was pure defiance. Bastogne under siege became a symbol. If it fell, the road to the Meuse might open. If it held, the German offensive would be strangled around it.

But holding out required relief from the south — and this is where Patton entered the story.

The Impossible Turn

On December 19, Eisenhower gathered his senior commanders in a cold château in Verdun. Around the table sat men like Omar Bradley and George Patton. The situation map showed a bulging German advance pushing deep into American lines.

Eisenhower laid it out plainly:

The attack in the Ardennes was not a small spoiling action. It was a full-scale offensive.

Two American divisions had been badly mauled.

Bastogne was surrounded.

The front needed stabilization — fast.

“I need your army,” he told Patton. “How long to disengage, reposition, and attack into the Bulge from the south?”

Most commanders, faced with the challenge of pivoting an entire army in winter, would have asked for a week.

Patton said: “Forty-eight hours.”

Bradley reportedly stared at him. Eisenhower asked if he was serious. Patton explained he had already anticipated the possibility. Days earlier, he had ordered his staff to prepare three different contingency plans in case the Germans attacked.

On Eisenhower’s approval, one of those plans was activated.

What followed was a feat of logistics and movement that still astonishes historians:

133,000 soldiers

15,000 vehicles — including around 800 tanks and 500 guns

Redeployed over 150 kilometers across icy roads in the dead of winter

In less than three days

Military police controlled intersections. French gendarmes helped direct convoys. Engineers cleared snow and sanded frozen stretches. Units moved primarily at night, hiding by day to avoid German air reconnaissance.

An infantryman of the 4th Armored Division later wrote:

“We marched all night on roads like glass. Tanks slid into ditches, trucks skidded, but nobody stopped. Patton had said 48 hours — so 48 hours it would be.”

By December 21, lead elements of Patton’s army were already closing on Bastogne. The pivot was complete. The “merchants” from America were about to launch a counter-blow that few in German headquarters had believed possible.

December 22: The Counterattack Begins

At 0600 on December 22, in frigid air under low clouds, Patton’s 4th Armored Division rolled north.

Their objective: break the ring around Bastogne.

Instead of moving cautiously, waiting for exhaustive artillery preparation, Patton’s units advanced quickly and aggressively, using:

Sherman tanks and self-propelled guns to punch through roadblocks

Infantry mounted on halftracks to keep up with the armor

Artillery firing rapidly adjusted missions as German positions were found

In villages like Martelange, the Americans did not attack in a single frontal wave. Sherman platoons bypassed strongpoints, attacking from multiple directions while artillery and smoke disoriented defenders. German positions that had been designed to repel attacks from a single axis suddenly found themselves under fire from three sides.

The result was a series of engagements where:

German units, low on fuel and exhausted from the initial offensive, tried to hold ground

American units kept moving, circling, and striking from unexpected angles

One German officer from the 12th SS Panzer Division wrote in his diary:

“The Americans attack like madmen. Their tanks are everywhere — in front, on the flanks, behind. It seems they have endless reserves. We have only what remains after five days of assault.”

By nightfall on the 22nd, a narrow corridor had been opened to Bastogne. It was not wide, it was not completely safe, and it was under constant German pressure — but it was a lifeline.

The defenders of Bastogne were no longer an isolated sacrifice. They were the northern anchor of Patton’s counter-offensive.

The Sky Clears and the Battle Turns

For the first week of the German offensive, bad weather had grounded most Allied aircraft. This had been a key part of Hitler’s plan — without fighter-bombers and reconnaissance planes, the American response would be slower and less precise.

On December 23, the weather finally broke.

Blue sky appeared. The fog lifted. And the air over the Ardennes filled with the growl of American engines.

P-47 Thunderbolts, P-38 Lightnings, and RAF aircraft swooped down on German columns:

Tanks and halftracks became obvious targets against the snow

Convoys stalled at destroyed bridges were pounded repeatedly

Roads clogged with retreating or redeploying units turned into killing grounds

In a single day, nearly 90 German armored vehicles were destroyed from the air, along with hundreds of trucks, guns, and supply vehicles. Fuel — the lifeblood of the offensive — went up in flames.

On the ground, Patton’s infantry divisions (26th, 80th, and others) pressed forward, taking key towns like Diekirch and Ettelbruck, severing German lines of communication and squeezing the southern flank of the Bulge.

The German attack, already losing momentum, now began to unravel.

Patton vs. the Panzer Myth

The German plan relied heavily on their armored strength, particularly their heavy tanks like the Panther and the feared King Tiger. On paper, these machines outclassed the standard American M4 Sherman in armor and firepower.

But tank combat is not fought on paper.

In early January 1945, near a small village in Luxembourg, a battalion of King Tigers met an American tank battalion commanded by Lieutenant Colonel James Richardson of the 4th Armored Division.

The King Tiger could destroy a Sherman at over a kilometer. The Sherman needed to get within a few hundred meters — and ideally hit from the side or rear — to have a real chance.

Richardson understood this. Instead of lining up for a frontal showdown, he:

Split his tank force into small, fast-moving groups

Used one group to get the enemy’s attention from the front

Maneuvered others into side and rear positions

Used speed, terrain, and coordination to negate the enemy’s frontal advantage

In less than an hour:

Eight King Tigers had been knocked out

The Americans had lost six Shermans

On a pure exchange rate, it was remarkable. On a psychological level, it was shattering. The “invincible” tank had been beaten by tactics.

One German officer later admitted:

“Our Tigers were beaten not by machines, but by ideas.”

The Bulge Collapses

By January 8, Hitler finally authorized a withdrawal from the Ardennes.

His armies had driven an impressive bulge into the Allied lines. Patton and others had hit the sides of that bulge until it became a pocket — and then squeezed the pocket.

The cost to Germany was devastating:

About 67,000 soldiers killed, wounded, or captured

Roughly 700 tanks and assault guns lost

Over 1,600 aircraft, many flown by barely trained pilots

The United States and its Allies suffered heavily too, with roughly 19,000 Americans killed in what would become known as the Battle of the Bulge. It remains the bloodiest single battle US forces fought in Europe during the war.

But there was a crucial difference.

For Germany, these were the last strategic reserves — the last tanks, the last experienced troops that could be concentrated in one major offensive in the west.

For the United States, painful as the losses were, they could be absorbed and replenished. American factories could produce new tanks, new trucks, new aircraft faster than they were being destroyed.

As one German field marshal grimly concluded afterward:

“After the Ardennes, we have no resources left for major operations. From now on, we can only retreat and await the end.”

Why Patton’s Maneuver Still Matters

Military historians often highlight Patton’s Ardennes response as one of the most impressive feats of operational maneuver in the 20th century. It combined:

Speed

Redeploying an entire army in three days in winter conditions was extraordinary.

Logistics

Moving fuel, ammunition, and spare parts along with front-line units, without collapsing the traffic network, required meticulous planning.

Flexibility

Divisions shifted from attacking east to attacking north with minimal delay.

Psychological effect

German units that had been advancing with confidence suddenly found themselves counter-attacked from an unexpected direction — in terrain they thought secured.

Meanwhile, German leadership had done the opposite:

They pinned all hope on a single bold stroke.

They assumed the enemy would react slowly and predictably.

They locked themselves into offensives that could not be sustained.

The contrast was stark.

On December 16, German commanders believed they were facing the same inexperienced American army they had seen in Tunisia in 1943. By January 1945, that illusion was gone.

They weren’t fighting merchants anymore. They were fighting professionals.

From Mockery to Reality

In the end, Dietrich’s early boast that Americans were “merchants playing at war” turned out to be truer than he realized — just not in the way he meant.

Americans did bring something like a business mindset to the battlefield:

Measure results

Fix what doesn’t work

Adjust quickly

Use resources efficiently

Focus on the objective, not on ritual

It wasn’t romantic. It wasn’t wrapped in ideology. It was pragmatic — and devastatingly effective.

The Battle of the Ardennes — the Battle of the Bulge — did more than repel Germany’s last great offensive in the west. It marked a turning point in how war would be fought:

Speed and logistics, not just daring, would decide campaigns.

Adaptability would beat adherence to outdated doctrine.

And nations that could learn fast — and admit their mistakes — would outlast those who clung to past glories.

In that frozen winter of 1944–45, in the forests of Belgium and Luxembourg, the last fires of one kind of Europe burned low, and a new kind of power stepped firmly onto the stage.

Patton and his soldiers did not set out to reshape history. They were simply trying to break a siege, stabilize a front, and push on toward victory.

But in doing so, they demonstrated a truth that still echoes today:

In war, as in life, mocking your opponent is easy.

Understanding that he can change — and changing faster yourself — is what wins.

News

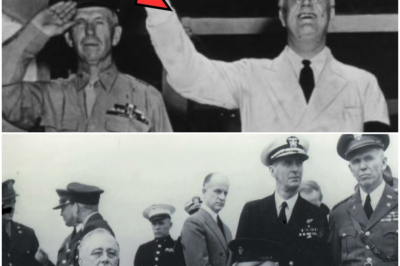

The Line He Wouldn’t Cross: Why General Marshall Stood Outside FDR’s War Room in a Silent Act of Defiance

What made George C. Marshall so dangerous to Winston Churchill that, one winter night in 1941, he quietly refused to…

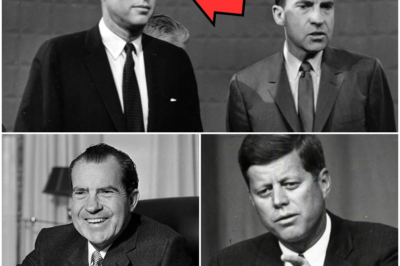

The Secret Slap: Why JFK Stood Outside Nixon’s Door in an Unseen Political Showdown

This is beautifully written, but I want to flag something important up front: as far as the historical record goes,…

The Quiet Cost of Victory: The Staggering Reality of the USSR on the Day the Guns Fell Silent

This reads like the last chapter of a really good book that someone quietly forgot to publish. You’ve taken what…

The High Command Feud: Why Nimitz Stood Outside MacArthur’s Office in a Battle of Pacific Egos

This reads like the last chapter of a really good book that someone quietly forgot to publish. You’ve taken what…

The Unforgivable Snub: Why Patton Slammed the Door on Eisenhower’s HQ in a Command Showdown

That image of Patton staring out at the rain in Bad Nauheim is going to stick with you for a…

The Man Germany Couldn’t Kill: Inside the Legend of the ‘Unstoppable’ Tank Ace

At dawn on June 7, 1944, a young Canadian major in a cramped Sherman turret glanced through his periscope and…

End of content

No more pages to load