The Fracture That Nearly Broke Victory: How Montgomery Tested the Limits of the Allied Command

The popular memory of the Second World War often paints the Western Allies as a unified force—partners moving in flawless coordination across France, Belgium, and into Germany. Yet beneath the surface of cooperation lay serious tensions, none more consequential than those involving Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery. His ambition, public confidence, and rigid strategic philosophy strained the Allied command structure at a time when unity was not merely valuable but essential for victory.

This is the story of how close the alliance truly came to fracturing—and how it survived.

A Commander Out of Context

When the Normandy invasion began, Montgomery was not merely another general. He was Britain’s most celebrated field commander, the victor of El Alamein, the man credited with halting German momentum in North Africa. His stature, both at home and among many in the British Army, was immense.

But success in the desert shaped expectations that did not translate smoothly into the far more complex campaign in Western Europe.

In North Africa, Montgomery commanded a unified army. In Europe, he stepped into an enormous multinational coalition—one increasingly led by the United States, whose industrial and military strength now surpassed that of Britain. The shift in power was undeniable.

Montgomery struggled to adjust. The man who had once commanded the British war effort now served within a partnership in which he no longer held natural primacy. Eisenhower was Supreme Allied Commander. The momentum, manpower, and material weight belonged increasingly to the American armies.

For Montgomery, this change was not simply structural—it was personal.

The First Cracks After Normandy

After the breakout from Normandy in late July 1944, American forces surged forward dramatically under General George S. Patton. Montgomery’s 21st Army Group, advancing through more constrained terrain, moved more slowly.

The disparity was understandable. The terrain, German defenses, and logistical conditions differed significantly across sectors. Yet Montgomery interpreted the shift as a threat. If the Americans continued advancing faster, Eisenhower might accelerate their strategic role, leaving Montgomery sidelined in the final phase of the war.

He had anticipated a sustained position as overall ground commander. He had not expected Eisenhower to assume direct command as early as September.

Montgomery did not hide his dissatisfaction.

He amplified it.

A Press Conference That Shocked the Alliance

In early September, Montgomery held a press conference that left American commanders stunned. He described the Normandy campaign almost entirely as his own strategic achievement, implying that the Americans had simply followed his design.

What he said may have pleased domestic audiences, but to U.S. generals who had suffered enormous casualties in the hedgerows, it was deeply offensive. Many believed Montgomery had minimized their sacrifices and exaggerated his own influence.

It was the first public sign that coalition discipline was slipping.

Behind closed doors, frustrations boiled. U.S. commanders demanded that Eisenhower respond firmly. British officials, equally alarmed, realized Montgomery’s unilateral rhetoric risked igniting diplomatic trouble between the two nations.

The Supreme Allied Commander chose restraint. Eisenhower understood that challenging Montgomery publicly would worsen the crisis.

But the damage had been done.

The Battle Over Strategy: Broad Front vs. Single Thrust

Montgomery’s proposal for the final drive into Germany rested on a bold assumption: concentrate all Allied supplies into his sector, drive hard into the Ruhr, and end the war quickly.

On paper, this “single thrust” plan had operational logic. Concentration of force is a classical principle of war.

But the proposal ignored political reality.

The United States now fielded the majority of Allied forces in north-west Europe. No American leader—military or political—would accept sidelining their armies so that a British general could lead the decisive advance into Germany.

Eisenhower understood this instantly. Montgomery did not, or refused to see it.

The resulting tension fed a growing divide:

American generals saw Montgomery as dismissive and inflexible.

Montgomery saw American command as inexperienced and overly political.

Both perspectives contained an element of truth.

Toward Market Garden: Strategy Becomes Personal

By September 1944, tensions were reaching a breaking point. Into this volatile atmosphere came Montgomery’s most ambitious plan: Operation Market Garden.

For Montgomery, Market Garden was more than a military operation. It was an opportunity to prove that his vision—a decisive strike into the northern Netherlands—could end the war before winter. It was also a chance to restore British prestige at a moment when American ascendancy was unmistakable.

But the operation demanded near-perfect execution:

airborne forces dropped miles from their objectives,

a single narrow highway vulnerable to counterattack,

supply lines already overstretched,

intelligence warnings about German armored divisions around Arnhem.

Many of these concerns were raised within planning meetings. American airborne commanders voiced them. Intelligence officers highlighted the risks.

But Montgomery’s confidence overshadowed adversity. He believed German forces were too disorganized to mount serious resistance.

The result was an operation built on optimistic assumptions and fragile logistics.

A Risk Eisenhower Could Not Block

Eisenhower approved Market Garden reluctantly. He knew rejecting it outright would inflame the already delicate relationship. Britain regarded Montgomery as a national symbol; Churchill’s government would have been enraged by a public rebuke.

So Eisenhower allowed the plan to proceed—not because he believed in its infallibility, but because coalition cohesion mattered more.

The operation began on September 17th. Problems appeared almost immediately:

communications failures,

unexpectedly strong resistance,

armored German units positioned exactly where intelligence had warned,

delays along “Hell’s Highway.”

Despite brilliant displays of courage by American, British, and Polish paratroopers, the plan required speed that the battlefield simply did not allow.

Nine days later, the last British airborne forces withdrew from Arnhem. The Allies had gained a foothold but failed to cross the Lower Rhine.

Montgomery, however, publicly described the operation as 90% successful—an assessment that infuriated American commanders.

It was a turning point in Allied relations.

A Command Structure Strained to the Breaking Point

In the months after Market Garden, the cracks widened:

American officers increasingly viewed Montgomery as unwilling to accept responsibility.

British officers worried that conflict between Montgomery and the Americans would jeopardize their nation’s wartime influence.

Eisenhower spent enormous energy mediating disputes and preventing political backlash.

Trust had become fragile. Every strategic debate carried the weight of accumulated frustration.

This was one of the closest moments the Allied coalition came to unraveling—not through defeat in the field, but through discord at the top.

The Rhine and the Final Phase of the War

Montgomery continued to advocate for a renewed concentration of force in the north as the Allies approached the Rhine. Once again, he requested priority supplies, and once again American commanders resisted.

Patton’s dramatic crossing of the Rhine—not to mention his rapid exploitation—undercut Montgomery’s argument that only a meticulously planned assault could succeed.

Yet Montgomery’s own Rhine crossing, Operation Plunder, was executed with skill and remains one of the most disciplined river operations in military history. His strengths as a planner were undeniable.

But even this success could not erase the lingering perception that Montgomery’s approach to coalition warfare was flawed—not tactically, but politically.

The Final Friction

Near the war’s end, Montgomery gave a speech implying that he had taken charge of American forces in the north due to superior insight. The statement was technically correct but disastrously phrased.

American commanders erupted in anger. Eisenhower was once again forced to intervene.

A single press conference at this stage could have soured bilateral relations just as the Allies prepared the final collapse of Germany.

That it did not is testament to Eisenhower’s steady leadership, not Montgomery’s restraint.

The War Ends, but the Resentment Does Not

After victory, the commanders wrote their memoirs—and the old tensions resurfaced with new force.

Montgomery defended Market Garden, claimed his strategy would have ended the war earlier, and portrayed the Normandy campaign as a personal creation.

American generals responded sharply:

Bradley wrote of Montgomery’s limited strategic imagination.

Patton was openly scathing.

Even Eisenhower felt compelled to correct the historical record.

The post-war narrative battle revealed what wartime diplomacy had concealed: many senior American officers genuinely believed Montgomery’s actions had come dangerously close to breaking Allied unity.

A Balanced Legacy

Montgomery remains one of Britain’s most capable and complex wartime leaders. His brilliance at El Alamein, his organizational rigor, and his emphasis on preparation saved lives and restored British morale.

But his wartime record cannot be separated from his personality:

confident to the point of rigidity,

brilliant yet inflexible,

protective of British prestige,

dismissive of opposing views,

prone to public statements that jeopardized coalition harmony.

The Allied coalition endured not because disagreements were absent, but because Eisenhower and other leaders absorbed the friction and refused to let ambition overshadow unity.

Montgomery was indispensable.

He was also destabilizing.

Both statements are true.

The Untold Lesson

The hidden story of the Allied victory is not one of perfect cooperation. It is one of fragile unity preserved under immense pressure.

Coalitions are strongest not when their members agree, but when they understand what must never be allowed to break.

Montgomery tested that boundary repeatedly.

Eisenhower held it together.

And in that tension—in that imperfect, contentious, sometimes volatile partnership—the road to victory was built.

News

AMERICA’S ATLANTIS UNCOVERED: Divers Just Found the Sunken City Hiding Beneath the Surface for a Century

Beneath 1.3 Billion Tons of Water: The Search for California’s Lost Underwater City A Lake That Guards Its Secrets Somewhere…

RACIST CHRISTMAS? Joy Reid Fuels Holiday Firestorm by Sharing Video Claiming ‘Jingle Bells’ Has Blackface Minstrel Origins

Joy Reid Shares Viral Video Claiming “Jingle Bells” Has Minstrel-Era Links — Sparking a Heated Holiday Debate A short video…

NUCLEAR OPTION SHOCKWAVE: RFK Jr. Executes Total Ban on Bill Gates, Demanding $5 Billion Clawback for ‘Failed Vaccine’ Contracts

In a seismic power play that is sending shockwaves through the global public health establishment, the Department of Health and…

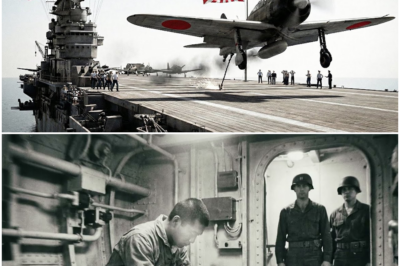

THE ULTIMATE BLUNDER: The Japanese Pilot Who Accidentally Landed His Zero on a U.S. Aircraft Carrier in the Middle of WWII

THE ZERO THAT LANDED ON A U.S. CARRIER: How One Young Pilot’s Desperate Gamble Changed the Pacific War** April 18th,…

THE ULTIMATE SHADE: What Montgomery Fumed Behind Closed Doors When Patton Beat Him to the Rhine Crossing

THE NIGHT PATTON STOLE THE RHINE: The Rivalry, The Politics, and the Crossing That Changed the End of World War…

THE WEEK OF ANNIHILATION: What a German Ace Discovered When He Landed—5,000 Luftwaffe Planes Destroyed in Just 7 Days

THE DAY ERICH HARTMANN REALIZED THE LUFTWAFFE WAS FINISHED January 15th, 1945 — A Sky Ace Confronts the Collapse of…

End of content

No more pages to load