The Race to Messina: How Patton Outpaced Montgomery and Redefined Allied Leadership

In the summer of 1943, as the Allies prepared to invade Sicily, British and American commanders entered the last major campaign before the liberation of mainland Europe. The operation, code-named Husky, marked the first time the Western Allies would conduct a large-scale invasion together, coordinating amphibious, airborne, and ground forces across a vast front.

On paper, the hierarchy was clear.

Britain, with years of combat experience, would lead the main thrust.

America, newer to the European theater, would provide support.

Yet what unfolded over the next five weeks challenged those assumptions, reshaped Allied relations, and left behind one of the most memorable rivalries of the Second World War.

This is the story of the race to Messina—a contest one general never wanted and another refused to lose.

Two Armies, Two Philosophies

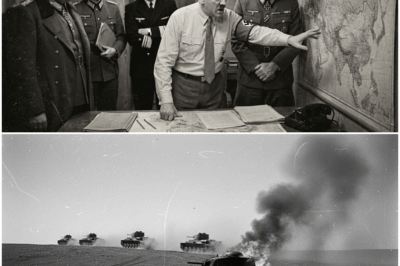

The Allied plan placed Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, commander of the British Eighth Army, in the central role. His army would land on the southeastern side of Sicily, then push northward toward the island’s ultimate prize: Messina, the gateway to mainland Italy.

Montgomery was viewed across Britain as the architect of the victory at El Alamein, the general who halted the Axis advance in North Africa and restored Allied confidence. His approach to warfare was meticulous and measured—built on preparation, secure supply lines, and well-coordinated assaults.

By contrast, the American Seventh Army was commanded by Lieutenant General George S. Patton Jr., whose style could not have been more different. Patton favored speed, boldness, improvisation, and relentless pressure. His formation was assigned a supporting role: land on the southern and western coasts, secure beachheads, and protect Montgomery’s left flank as the Eighth Army advanced toward Messina.

The divide between the armies was clear in the planning stages. British commanders were openly skeptical of American experience, recalling early setbacks in North Africa. Patton, highly aware of this perception, was determined to prove the American Army’s capability.

Montgomery saw the plan as a straightforward progression toward victory.

Patton saw it as an opportunity.

Operation Husky Begins

On July 10, 1943, the Sicily landings began under challenging conditions. Rough seas scattered airborne units, pushed landing craft off course, and complicated the initial assault. Despite this, both armies established beachheads.

Montgomery’s forces advanced up the eastern coast but soon encountered well-prepared defensive positions. German and Italian troops used Sicily’s rugged terrain to their advantage. Each ridge and town became a strongpoint, slowing the British advance to a methodical grind.

Meanwhile, Patton, having secured his initial objectives, began thinking beyond simple flank protection. The available routes to Messina were not confined to the eastern coastal road. There was also a longer but less fortified route along the north coast and another path through the island’s interior—both technically within the latitude of his command responsibilities.

Patton recognized something crucial:

If the British advance stalled, the Americans could reach Messina first.

And in Patton’s mind, that was an opportunity he could not ignore.

Patton’s Shift Toward Palermo

Within days of the landings, Patton launched a rapid push westward toward Palermo, Sicily’s capital. This was not part of Montgomery’s vision for the campaign, nor was it a requirement for protecting the British flank. But by seizing Palermo, Patton achieved several objectives at once:

He captured a major port that improved American logistical support.

He demonstrated to Allied command—and to the American public—that his army could operate independently and effectively.

He positioned himself advantageously for a push along the northern coast toward Messina.

Palermo fell on July 22, only twelve days after the landings. It was a stunningly fast advance, especially compared to the difficult fighting on the eastern front.

Montgomery was not pleased. To him, Palermo was a distraction from the main effort. To Patton, it was preparation for what came next.

The Race Takes Shape

By early August, Patton’s Seventh Army controlled much of western and central Sicily, leaving him poised to sweep east along the northern coastal road. This route, though narrow and difficult, was less heavily defended than Montgomery’s eastern approach.

British intelligence soon noticed the American movements and informed Montgomery. His initial reaction was disbelief. He still viewed the American role as supporting, not competing. The idea that Patton might be driving directly for Messina seemed to him out of step with the agreed plan.

But the reports continued. American forces were advancing rapidly. They were closer to Messina than the British. And their pace was increasing, not slowing.

Montgomery now understood what Patton had been planning all along.

A race was underway—one Montgomery had neither expected nor wanted.

A Tale of Two Advances

The differences between the two armies’ progress became increasingly stark:

Montgomery’s Eighth Army moved along a narrow corridor defended by experienced German units. Each town demanded careful coordination and preparation. Progress was steady but slow, consistent with Montgomery’s doctrine.

Patton’s Seventh Army moved through lighter resistance. Patton employed flexible tactics: amphibious landings to outflank defenders, rapid motorized thrusts, and bold maneuvering. His subordinates understood the urgency; their drive toward Messina took on the energy of a competitive sprint.

By mid-August, the American advance was measured in miles per day while the British advance was measured in yards.

Montgomery was now fully aware he would not reach Messina first unless he dramatically accelerated his operations.

The Final Push

On August 16, Montgomery’s headquarters received definitive intelligence:

American forces had entered the outskirts of Messina.

He issued a final series of urgent orders, urging his troops forward with unprecedented speed. But the terrain and German rearguard actions made rapid progress nearly impossible.

The next morning, August 17, 1943, the American Third Division marched into Messina. Patton arrived shortly afterward, posing for photographs that would soon circulate worldwide. American flags flew in the city center.

A few hours later, Montgomery entered Messina to find Patton already there, smiling cordially.

Accounts from both sides record a tense exchange of congratulations—polite on the surface, competitive beneath.

Patton later described the moment simply:

“We got there first.”

Montgomery’s Reaction

While Montgomery maintained official decorum, his private reaction was markedly different. Senior members of his staff recorded his disappointment and frustration. He believed that Patton’s independent maneuvers had jeopardized coordination and exaggerated the importance of reaching Messina itself, which the Germans were already abandoning.

Montgomery later wrote that both armies succeeded and that the Americans had merely taken the longer, less dangerous route. But the sting remained. For the remainder of the war, he regarded Patton with a mixture of respect, caution, and rivalry.

Patton, by contrast, embraced the competitive edge of the moment.

To him, the race to Messina symbolized the arrival of the American Army as an equal partner.

What the Race Revealed

The Sicily campaign demonstrated several key truths:

1. The United States Army had matured.

The rapid maneuvers, improvisation, and operational initiative displayed by American forces proved they were fully capable of independent, complex action.

2. British-American command dynamics were changing.

Montgomery’s assumption of British primacy was no longer automatically accepted.

3. Patton and Montgomery represented contrasting doctrines.

One valued precision and preparation; the other velocity and audacity. Sicily showed both strengths—and both limitations.

4. The race to Messina reshaped Allied perceptions.

After Sicily, the idea of Americans as junior partners faded permanently.

Legacy of the Race

The rivalry between the two generals endured for the rest of their lives.

Montgomery viewed Patton as reckless.

Patton viewed Montgomery as overly cautious.

Yet their competition produced something larger than personal achievement:

It proved that Allied diversity of thought—methodical and aggressive, slow and fast, planned and improvised—could combine to achieve decisive victories.

The race to Messina was not just a contest of personalities.

It was a turning point in Allied cooperation and a moment when the balance within the coalition subtly shifted.

From that day onward, no one—not even Field Marshal Montgomery—could reasonably deny the operational strength of the American Army.

And Patton, for all his flaws, had made that point in the most dramatic way possible.

News

The Forbidden Library: N@zi Colonel Discovers Banned Books in Captivity—And What He Read Destroyed His Beliefs

From Captive Officer to Scholar of Freedom: The Remarkable Transformation of Friedrich Hartman In the final year of the Second…

The Defector’s Strike: Nazi Spy Master Learned Democracy in US Captivity—Then Wrecked His Old Comrades

The Noshiro’s last bubbles had scarcely broken on the surface before the sea erased her presence. Oil spread in a…

The ‘Stupid’ Alliance: Hitler’s Furious, Secret Reaction to Japan’s Massive Betrayal

The Noshiro’s last bubbles had scarcely broken on the surface before the sea erased her presence. Oil spread in a…

The Tactic That Failed: One Torpedo, One Ship, and the Moment Admiral Shima Ran Out of Doctrine

The Noshiro’s last bubbles had scarcely broken on the surface before the sea erased her presence. Oil spread in a…

Atlantic Apocalypse: How Dönitz’s Deadly U-Boat ‘Wolf Packs’ Lost 41 Subs in One Month

Unmöglich”: What German High Command Really Said When Patton Did the Impossible On December 19, 1944, a phrase circulated through…

History’s Verdict: The Nazi Who Faced US Justice Before War’s End—A Story You Haven’t Heard

The Execution of Kurt Bruns: The First Nazi War Criminal Shot by U.S. Forces On June 15, 1945—only five weeks…

End of content

No more pages to load