When the Desert Changed the Future: How the Gulf War Shattered Soviet Military Assumptions

When Soviet military commanders watched the rapid destruction of the Iraqi army by U.S.-led coalition forces in January and February 1991, they were not merely observing a distant regional conflict. They were witnessing the collapse of ideas that had shaped Soviet military doctrine, strategic planning, and ideological confidence for nearly half a century.

Inside Soviet analytical circles, the Gulf War was not interpreted simply as the defeat of one army by another. It was understood as a revelation: proof that the character of modern warfare had changed fundamentally—and that the Soviet Union had failed to keep pace.

By the time Operation Desert Storm began, the Soviet state was already under severe strain. Politically exhausted, economically weakened, and ideologically fragmented, it nevertheless retained one enduring belief: that its military remained one of the two great pillars of global power. The Iraqi army, after all, had been trained, equipped, and doctrinally shaped by Soviet advisers. Its tanks, air defenses, command structures, and operational concepts reflected decades of Soviet influence.

If Iraq collapsed quickly, then something far more consequential was being exposed.

A Shock, Not a Surprise

What unfolded over weeks of aerial bombardment and just seventy-two hours of ground combat was interpreted by Soviet observers not primarily as an Iraqi failure of morale or leadership, but as evidence that American warfare had entered a qualitatively different era.

The speed, coordination, precision, and dominance displayed by coalition forces contradicted long-held Soviet assumptions about how wars between modern armies would be fought. This realization did not arrive gradually. It arrived as a shock.

Senior officers from the Soviet General Staff, air defense specialists, armored warfare theorists, and intelligence analysts followed the conflict closely. They studied satellite imagery, intercepted communications, diplomatic briefings, and—most unsettlingly—live television broadcasts.

The appearance of real-time battlefield coverage was itself a novelty. For many Soviet officers, the sight of armored formations destroyed before contact, command centers neutralized without direct assault, and entire divisions rendered ineffective in hours was profoundly destabilizing.

The Collapse of Mass Doctrine

Since the Second World War, Soviet military doctrine had rested on several core assumptions: mass, depth, and endurance. Wars were expected to be decided by the ability to mobilize enormous forces, absorb losses, and sustain operations across vast theaters. Precision was desirable, but attrition remained central.

In Iraq, these assumptions appeared obsolete.

Coalition forces did not seek attrition in the traditional sense. They sought paralysis.

One of the most disturbing observations for Soviet commanders was the near-total collapse of Iraqi command and control. Communications were severed early, radar networks blinded, and field commanders isolated. This contradicted the belief that centralized control, reinforced by redundancy and discipline, could withstand intense pressure.

Instead, the Americans demonstrated that information dominance could shatter an army without annihilating it physically. The battlefield was no longer merely geographic. It was informational.

A Mirror Held Too Close

Equally troubling was the performance of Soviet-designed weapon systems. T-72 tanks, long considered reliable within Warsaw Pact planning, were destroyed at ranges Iraqi crews could neither detect nor respond to. Soviet air defense systems—SA-2s, SA-6s, radar-guided guns—proved unable to counter stealth aircraft, cruise missiles, and coordinated electronic warfare.

Soviet analysts understood immediately that this was not simply an Iraqi problem. Similar systems formed the backbone of their own defensive architecture.

Within planning departments and military academies, an unspoken conclusion spread: this was a rehearsal. If the Soviet Union ever faced the United States directly, the outcome might be decided not in months or weeks, but in days.

A Gap That Could Not Be Closed

This realization arrived at the worst possible moment. Even as Soviet commanders grasped the implications, they understood that the resources required to adapt—advanced electronics, computing power, satellite networks, precision manufacturing—were precisely those the Soviet economy could no longer reliably produce.

The gap revealed in the deserts of Iraq was not merely military. It was civilizational.

The Gulf War became, in internal Soviet discourse, less a foreign war than a mirror reflecting decades of stagnation, doctrinal rigidity, and technological isolation. Officers trained to plan massive tank offensives across Central Europe now faced the reality that such plans would likely fail catastrophically.

The battlefield had moved beyond the paradigms they had mastered.

The Air War as Revelation

From the Soviet perspective, the decisive phase of the war was not the ground offensive that ended it, but the air campaign that preceded it.

Soviet air defense specialists followed the opening night of Operation Desert Storm with particular intensity. Iraq’s air defense system had been constructed largely along Soviet lines: layered missile belts, early-warning radars, centralized command nodes, and interceptor aircraft designed to respond in coordinated fashion.

On paper, it resembled the systems intended to defend Eastern Europe.

In practice, it collapsed almost immediately.

Stealth aircraft played both a symbolic and practical role. Long debated within Soviet circles, stealth had been viewed by some as a marginal advantage. Iraq provided an answer Soviet analysts did not like.

Radar invisibility combined with precision-guided munitions rendered layered air defense questionable. Electronic warfare compounded the effect, flooding operators with false targets and disrupting communications. Iraqi defenders were not merely suppressed; they were overwhelmed cognitively.

A Different Philosophy of Command

Equally unsettling was the coalition’s command structure. Soviet doctrine emphasized centralized control and detailed planning. The coalition demonstrated decentralized execution within an integrated information framework.

Pilots received real-time updates. Targets were reassigned dynamically. Intelligence flowed continuously between satellites, aircraft, and command centers. To Soviet observers, this suggested a level of flexibility and responsiveness their own systems struggled to achieve.

Precision-guided munitions became a central topic of postwar analysis. Infrastructure targets were destroyed efficiently, contradicting the Soviet emphasis on mass firepower. Precision, it became clear, altered the economics of war. A force that could strike accurately did not need to strike often.

The Fall of Armored Certainty

Perhaps no community within the Soviet military was more shaken than the armored warfare establishment.

Tanks had been the centerpiece of Soviet military identity since the Second World War. From Kursk to Berlin, armored forces symbolized mobility and power. Iraqi tank formations, equipped largely with Soviet-designed vehicles, were assumed to represent a credible modern force.

Their destruction forced a reckoning.

There were no prolonged tank-on-tank battles. Iraqi armor was detected, targeted, and destroyed before it could respond. Thermal imaging, advanced optics, and superior situational awareness turned visibility into a weapon.

Night fighting capability proved decisive. Coalition forces maneuvered and engaged effectively in darkness, while Iraqi crews were effectively blind. Night, once a constraint, became an advantage.

Even accounting for export-model limitations, the vulnerabilities were clear. Ammunition storage, crew survivability, and sensor integration lagged behind Western designs. More importantly, tanks no longer functioned as independent decisive weapons. They became targets within a broader sensor-shooter network.

Systemic Failure, Not Tactical Error

Soviet analysts increasingly concluded that Iraq had not been defeated by clever exploitation of weakness, but by systemic realities. Centralized control, reliance on radar, limited electronic resilience—these were structural vulnerabilities.

The concept of operational depth, long central to Soviet thought, also appeared compromised. Coalition forces bypassed and enveloped Iraqi formations faster than reinforcements could arrive. Depth provided no protection when time itself had been denied.

This led to an uncomfortable insight: the future battlefield would be transparent. Satellites, airborne sensors, and real-time intelligence made concealment increasingly difficult. Geography mattered less than information.

A Cognitive Revolution

Beyond weapons and platforms, Soviet thinkers confronted a more abstract conclusion. The war had been decided less by destruction than by decision-making.

Coalition forces operated inside the Iraqi decision cycle from the first hours. Orders were issued and executed faster than Iraqi command structures could comprehend. By the time Iraqi commanders reacted, circumstances had already changed.

This was described increasingly as a cognitive shift in warfare. Tempo was no longer tied primarily to maneuver and mass, but to information processing and adaptability.

Soviet doctrine prized predictability and control. Iraq demonstrated that flexibility could outperform exhaustive planning. The battlefield became a dynamic system rather than a linear problem.

A Future Without Capacity

These conclusions arrived too late.

The Soviet Union lacked the economic, industrial, and organizational capacity to respond meaningfully. Defense industries struggled with electronics. Budgets shrank. Organizational culture resisted decentralization.

Reform was understood as necessary—and increasingly impossible.

When the Soviet Union dissolved later in 1991, the lessons of the Gulf War passed to successor states burdened with fewer resources and greater uncertainty. Russian military thought would revisit these ideas repeatedly, selectively modernizing in areas like electronic warfare and missile forces, but never fully closing the gap revealed in Iraq.

The End of an Era

In Soviet and later Russian military education, the Gulf War became a case study not in defeat, but in obsolescence. It illustrated what happens when industrial-age forces confront post-industrial systems.

The tragedy, from the Soviet perspective, was not ignorance. The lessons were clear almost immediately. The tragedy was impotence.

The Gulf War did not defeat the Soviet military. It revealed its exhaustion.

For historians, the moment remains pivotal. It marked the end of a way of war defined by mass and endurance, and the beginning of one defined by information, precision, and speed.

When Soviet commanders watched the Iraqi army collapse in just seventy-two hours, they were not simply observing the end of a conflict. They were witnessing the end of an era—and the arrival of a future they no longer had the power to shape.

News

The Führer’s Fury: What Hitler Said When Patton’s 72-Hour Blitzkrieg Broke Germany

The Seventy-Two Hours That Broke the Third Reich: Hitler’s Reaction to Patton’s Breakthrough By March 1945, Nazi Germany was no…

The ‘Fatal’ Decision: How Montgomery’s Single Choice Almost Handed Victory to the Enemy

Confidence at the Peak: Montgomery, Market Garden, and the Decision That Reshaped the War The decision that led to Operation…

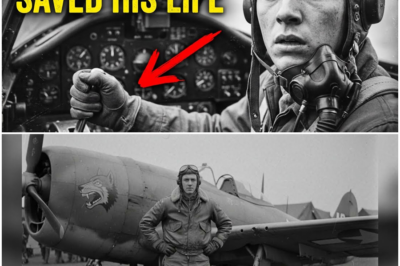

‘Accidentally Brilliant’: How a 19-Year-Old P-47 Pilot Fumbled the Controls and Invented a Life-Saving Dive Escape

The Wrong Lever at 450 Miles Per Hour: How a Teenager Changed Fighter Doctrine In the spring of 1944, the…

The ‘Crazy’ Map That Could Have Changed Everything: How One Japanese General Predicted MacArthur’s Secret Attack

The “Crazy Map”: The Japanese General Who Predicted MacArthur’s Pacific Campaign—and Was Ignored In the spring of 1944, inside a…

The Silent Grave: 98% Of Her Crew Perished in One Single Night Aboard the Nazi Battleship Scharnhorst

One Night, One Ship, Almost No Survivors: The Mathematics of a Naval Catastrophe In the winter darkness of December 1943,…

Matt Walsh Unleashes Viral Condemnation: “Just Shut the F* Up” – The Daily Wire Host Defends Erika Kirk’s Grief*

Matt Walsh Defends Erika Kirk Amid Online Criticism Following Husband’s Death WASHINGTON, DC — Conservative commentator and Daily Wire host…

End of content

No more pages to load