She had been fifteen minutes early and properly ridiculous about it: her favorite beige dress (the one that made her feel like the woman she had been before the car), lipstick in a soft red that made her feel like she still owned faces she could wear, hair pinned back in a loose chignon that took more courage than it should. She’d sat in her wheelchair at the corner table closest to the sidewalk, hands folded in her lap, scanning for the man whose profile had felt plausible and kind in their messages—Daniel, who had asked about her artwork and about the show she’d mentioned, who hadn’t made a fuss about the wheelchair when they texted.

She saw him across the street right on the dot. He stopped, scanned, and his face—when it fell on her chair—shut like a door. For a moment she watched, as if she were observing someone else. The man typed something quickly, and her phone buzzed: “Sorry, something came up. Can’t make it. Good luck.”

Her mouth went dry. She sat very still, as if the body that had carried her this far could hold one more disappointment without crumbling. She felt the old familiar splinter: reduction. Not Serena, the person with a quadrille of terrible coffee habits and a soft laugh, but a wheelchair and a story that made others walk away.

She considered leaving, for dignity’s sake. Finished the tea at the table, she told herself, as if a half-sipped cup could patch pride. She blinked back tears and pulled a sketchbook from her bag, pretending to draw. Her hands trembled enough that the lines blurred into a watercolor map.

Then a small voice broke into the scene like someone tipping a jar of stars onto the pavement.

“Hi,” said a little girl, solemn as if she had paused mid-proclamation to weigh her words. She had blonde pigtails tied with red ribbons and a stuffed unicorn clutched to her chest, one shoe untied. Her blue eyes were enormous with curiosity. “Why are you sad?”

Serena scrubbed the soles of her palms with the back of one hand and smiled with the practiced generosity she reserved for children and dogs. “I’m okay, sweetheart,” she said. “Are you lost? Where’s your—”

“Daddy’s right there,” the girl said, pointing with a sticky finger. A man hurried over, coat flapping like he’d been running errands and been made late by the gravity of the world. He was in his late thirties—handsome, yes, but not the kind of handsomeness that shouted; more the kind that quietly filled a room with order. He wore the look of someone used to being listened to, the CEO sort of composure that came from being responsible for more than his own lunch.

“Lily,” he said gently, but his eyes softened when they landed on Serena. He took in the tear tracks on her face, the empty chair across from her, and something in his stern line eased.

“I’m sorry if she scared you. She has a habit of escaping when I’m not looking.” He glanced at the little unicorn. “Is that Sparkle? Badgered my daughter into naming every toy with a ‘-le’ last week.”

“Sparkle,” Lily confirmed, and then, with the solemnity of a judge, she asked the thing children ask that adults are terrified to answer: “Why do you have wheels?”

The father’s face cooled into a polite rebuke. “Lily, that’s rude—”

Serena interrupted. “It’s okay, really. Ask away.” She folded her fingers around the stuffed animal their daughter offered like an offering. The toy was worn at the edges and smelled faintly of banana-scented sunscreen. Serena smiled at the girl; the smile arrived like a small sun.

“I was in an accident,” she said. “My legs don’t work like yours do, so I use this chair to go places. It helps, like how your daddy drives a car instead of walking everywhere.”

Lily nodded as if logic had been restored to the universe. “Can I sit with you? You look lonely. The nice lady probably wants to be alone.”

Serena laughed soft and honest. “Actually, I’d love the company—if it’s okay with your father.”

The man waited a beat, measuring. “Okay,” he said, and sat down without taking his eyes off her for a moment. “I’ll get the coffees while you tell me all about Sparkle,” he told Lily, and Lily hopped onto the chair that Daniel’s absence had left empty, setting her unicorn carefully on the table between them as if establishing boundaries.

“Daddy’s Adrien,” he said when he returned with two cups and a juice box for Lily in a paper carton she gingerly accepted like a treasure. “Adrien Blackwood.”

“Serena Hayes,” she offered back, embarrassed by the residual dampness around her eyes. She’d never liked pity; the word felt like sand in the mouth.

They talked because—sometimes that’s the way of it—words come easier across strangers than across people who already have everything expected of them. Adrien asked gentle questions about her design work, about how she worked from home and what kind of clients she preferred. He didn’t ask invasive things about the accident; he let her tell that story on her terms, and when she did talk about the car and the ambulance and the months of relearning, he listened the way people listen when they are not inventing a problem to solve.

When Lily’s small hand drew an earnest squiggle on a napkin, she announced emphatically, “Sparkle makes people happy when they’re sad. Do you want to hold her?” She placed the unicorn into Serena’s lap as if bestowing a priesthood.

Serena wrapped her fingers around the stuffed animal. The seams along Sparkle’s horn had been mended once, clumsy stitches in neon thread. It made the toy more human, in the way scars do. She breathed in the faint smell of crushed crayons and forgotten park afternoons and felt something in her chest click into a shape that resembled possibility.

Adrien sat down on the bench across from her. “I’m sorry about the man,” he said after a while, his voice low enough to not interrupt Lily’s nap with a father’s rhythm thrum against a shoulder. “I was in the shop across the street—Malcolm’s Gelato—and I saw him look at you. He typed something and walked away without bothering to meet your eyes. I was furious, honestly. Wanted to—” He stopped, swallowing something that wasn’t coffee. “—wanted to tell him off.”

Serena’s face flushed hot. “You saw that? I thought I had maybe misread it. Maybe I was expecting too much.”

“No,” Adrien said. “You didn’t misread it. I saw it. People like that are small, and not just because of what they can’t handle. They’re small because they refuse to be generous—for whatever reason.” He looked at Lily then, who had fallen asleep against his chest, thumb in her mouth. “Sometimes the best response to cruelty is kindness. Show someone their value, instead of wasting energy on people who would never see it.”

“You don’t even know me,” Serena said, because the polite fences of wariness were still in her, even as her hands relaxed around Sparkle. “You could be a man who just likes to rescue sad women from benches.”

Adrien’s smile was plain but honest. “I could be. But I’m a man who had a wife who died three years ago—cancer—and I’ve been raising a tiny hurricane alone since. I work long hours. I run a company that makes uncomfortable decisions, and I get exhausted. People have dated me for what I am, or for what I can give. Some thought my life with a child was just a prop. Some expected a fairy-tale version of parenthood until the tantrums started. That’s not what I want to re-create. When I watched you with Lily—for the short time that I did—you didn’t stiffen or make a performance out of kindness. You were human. That told me more than any profile ever could.”

Serena let out a laugh that dissolved into a sob and then something like steadiness. She told him things—an edited, dignified version of the night the car hit a light pole, the sterile hum of hospital rooms, the smell of antiseptic and rain. She told him about the months of physical therapy, the way her left fingers had been the first to remember how to hold a brush again, the slow resurrection of small details that meant life had not ended, only become stranger.

Adrien listened. When she described the man who had left, he exhaled a sound that was part anger, part relief. “I’m glad he didn’t stay,” he said finally. “Not because you were hurt, but because if he had, perhaps Lily wouldn’t have found Sparkle and decided the universe needed a new plan. Sometimes doors close so other ones can open. It’s a cliché, but true.”

They exchanged numbers that day because it felt like the right thing to do; Adrien typed his name and hit send with the same casual confidence he had when making investments. He wrote a message that evening—“Coffee again? Lily requests a playdate for Sparkle”—and Serena’s reply came with a tiny clumsy heart emoji, a punctuation she reserved for when she wanted to be brave and a little foolish.

Coffee turned into dinners. Dinners turned into Sundays that began with pancakes and ended with cartoons and ended with lullabies hummed softly enough to stitch a small child’s dreams. Adrien asked practical questions—Is the front door wide enough? Would I be in the way if I bring groceries?—and then listened to the answers, not with obligation but with a willingness to learn.

Lily, for her part, was fierce and precise in her judgments. “You’re different from the other women Daddy dates,” she said one rainy afternoon while they painted with tempera at Serena’s kitchen table. “The other ladies smile when Daddy’s there, but when it’s just me and them, they look like they want to go. You play with me even when Daddy isn’t watching.”

“Is that good or bad?” Serena asked.

“It’s good,” Lily declared. “Because I wanted a mommy who would like me for me. I asked the universe, and the universe sent you sitting sad at the café.” She touched Sparkle’s frayed horn reverently. “I knew you were for both of us.”

The slow accumulation of ordinary tenderness wrapped around Serena like a new skin. Adrien never made the wheelchair into an obstacle to be overcome. He asked practical things when needed, sure—Would a ramp be better than the threshold? How can I help with transfers?—but he did not make pity the foundation of their relationship. He celebrated Serena’s small triumphs; when she took a commission she feared she couldn’t handle, he suggested a practical schedule and then applauded when she completed the piece, frame sent and client pleased. When she had a design that she feared was too personal, he said, “That you’re brave enough to make it matters more than whether other people get it.”

If romance is built on repetition, their repetition was made of quiet steadiness. He came back when he said he would. He introduced her to his team not as a charity story but as a partner he trusted, and when colleagues blinked at the sight of a toddler dragging crayons across the conference room table, Adrien’s only response was a proud, “This is Lily. She’s kindly obsessed with unicorns.”

Months became a year. One evening, after a dinner that had turned into a marathon of building a sofa fort with cushions stolen from Serena’s living room, Lily asleep upstairs with a fever and a damp forehead pressed to Adrien’s shoulder, Serena sat next to him on the couch. They watched the city lights blink awake below them like a scattered constellation.

“You moved into my head,” Adrien said suddenly, his hand finding hers. There was an intensity in it that wasn’t the competence of a boardroom but the tenderness of someone who had been peering at life and found a surprise. “I kept thinking, this—this is what I want to come home to. Not because it’s tidy or easy, but because it’s honest. You are honest.”

Serena let her fingers rest in his. “I was left at a café once,” she said. “It was humiliating. But the man who left created a little space that a little girl filled. That was how my life rerouted, adrien. I don’t know if I would’ve chosen that ugliness, but I’m grateful for its consequence.”

He turned to her, eyes steadying. “Serena, I love you. Not despite anything. Because of the whole of you. The things you’ve lost and the things you still give. I can’t imagine my life without you and Lily in it. Will you marry me? Will you marry us?”

He didn’t make a show of it—no flash mob, no dramatic skyline banner. He took a small, simple ring from his pocket and asked there, on the couch between the sofa fort and the coffee table, where a half-assembled Lego dragon lay in a suspiciously strategic pile.

Serena’s answer came in a sob and a laugh and a yes that folded into his mouth like a homecoming. Lily, waking at the sound of adult voices, padded down the stairs and announced, sleepy-eyed and solemn: “I object to anyone being mean to my mama ever again,” and the words were said with such gravity that Adrien laughed until he cried.

Their wedding was small and luminous. They rented a little hall with high windows and bread-brown beams and, because life had taught them to choose what mattered, they asked Lily to be their flower girl. She took the job with the seriousness of one appointed to guard the sun. Sparkle rode in Lily’s basket among the petals, the unicorn’s frayed horn catching the light.

During Adrien’s vows he said, “A foolish man saw a wheelchair and walked away from the most extraordinary woman he’ll never know. His loss gave me the greatest gift: the chance to know you, to love you, and to build a life with you. You’ve taught Lily that kindness matters more than appearances, and you’ve taught me that strength comes in many forms.”

Serena’s vows were brief, like good design: clean, honest, and true. “I was left alone at a café, invisible and certain I would always be reduced to pity. Then a little girl with pigtails and a magic unicorn sat with me and saw me as someone to talk to, not something to be fixed. Adrien came back and stayed. Together you both gave me back what I thought I’d lost: the belief that I’m worthy of love exactly as I am.”

People cried; Lily stood and pronounced a solemn injunction about kindness that made everyone laugh and weep at the same time. They walked out into the afternoon as a family, and Serena felt the wheelchair beneath her like a part of her dress; it didn’t make her less beautiful. It made her whole.

Years later, when people asked how they met, Serena told the story with a shrug and a small conspiratorial smile. “I was left at a café,” she’d say. “And then the universe intervened with a little girl named Lily and a man who didn’t walk away.”

Adrien would add, “And I learned that sometimes showing up is the bravest thing a person can do.” He would smile at her, and at Lily, now collecting shells at the edge of the sea during a family holiday, and mean it with the bone-deep certainty of a man who had been given more than he could deserve.

Daniel’s name was a footnote in her past—an unkindness transformed into a narrow corridor through which something better had to pass. She did not hate him. She felt a strange sort of pity for people who could mistake fear for integrity. He had chosen in a single breath to walk away; Adrien had chosen to sit. The difference between them had been elementary and enormous.

Serena kept Sparkle on a bookshelf in her studio, the unicorn’s horn stitched up again when Lily had torn it in a fit of imaginative play. It bore the stains and markers of small, honest life. When a client asked why she kept a child’s toy in a professional space, she would say, “Because it reminds me that kindness is a currency that never devalues.”

People will tell you that love is something dramatic, an aurora of impossible gestures. For Serena, love was a series of returns: a man who returned after seeing a woman’s wheelchair; a child who returned her toy with the solemnity of a small priest; a father who returned home to find that his life could be larger than profit margins and boardrooms. It was a thousand little consistencies added up—dinner when the work day would have made leaving easy, coffee left beside the sketchbook, a hand in a crowded place when all other hands were busy with their own reflections.

And on, sometimes, the days when clouds gathered and old fears whispered, Adrien and Lily would catch her eye and remind her—in looks and small, steady gestures—that she had never been alone for long. The world, she learned, is a messy congregation of people choosing how they will treat one another. Daniel chose indifference; Adrien chose presence. Lily chose to give away her magic unicorn.

That afternoon at the café, a story closed and a different one, imperfect and luminous, began. They built a life from the second, kinder choice. It wasn’t a tidy destiny; it was laughter over spilled milk and backseat sing-alongs and midnight calls when someone was scared. It was learning the architecture of another person’s needs and laying bricks of ordinary grace.

Serena looked at her family across the table one evening—Lily asleep in Adrien’s lap, a blind bookmarked by a half-finished sketch of the city—and thought about doors closing and opening, about how the most human courage is the courage to sit down and stay. She ran her thumb over the worn seam of Sparkle’s horn and smiled.

“Thank you,” she whispered into the dim kitchen, and the house answered with the quiet warmth of people who had chosen, every day, to be more than small.

News

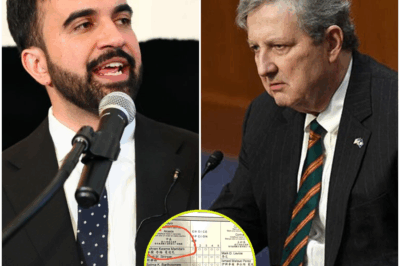

‘ARREST THAT MAN!’ Kennedy Unleashes National Fraud Probe, Exposing 1.4 Million ‘Ghost Votes’ in NYC Heist

THE RED BINDER ERUPTION — The Day Kennedy Turned Washington Into a Warzone Some political confrontations build slowly, like storms…

PROSPERITY CRACKED: Kennedy Shatters Joel Osteen’s Sermon, Exposing Financial Exploitation in 36 Seconds

A polished, well-choreographed evening service at Lighthouse Arena, 16,000 seats filled, lights sweeping across a cheering crowd ready to hear the…

His wife left him and their five children—10 years later, she returns and is sh0cked to see what he’s done.

The day Sarah left, the sky was gray with a light drizzle. James Carter had just poured cereal into five…

I installed a camera because my husband wouldn’t “consummate” our marriage after three months. The terrifying truth that was revealed paralyzed me…

I installed a camera because my husband wouldn’t “consummate” our marriage after three months. The terrifying truth that was revealed…

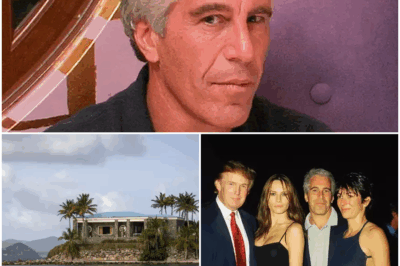

NEW FLIGHT DATA BOMBSHELL: ‘Disturbing Spike’ Uncovered on Epstein’s Island, Signaling Wider Network

Thousands of previously unreported flights to Jeffrey Epstein’s private island have been unearthed as part of a massive data investigation,…

Ella, twenty-two years old, grew up in poverty.

Ella, twenty-two years old, grew up in poverty. Her mother, had a lung disease. Her brother, could not go to…

End of content

No more pages to load