When Steel Became a Trap: Seven Warships That Exposed the Limits of Power at Sea

Warships are often introduced to the world with confidence bordering on certainty. They are described as deterrents, symbols of national will, and guarantees of security. Their silhouettes appear on posters and in speeches as proof that technology and planning have mastered uncertainty.

History suggests otherwise.

Across the Second World War, several celebrated vessels did not fail because of a single unlucky hit or an enemy’s brilliance alone. They failed because assumptions embedded in their design, doctrine, or deployment collapsed under real conditions. These ships did not merely sink. They revealed how easily confidence can turn into catastrophe.

7. HMS Hood: Speed Without Protection

For two decades, HMS Hood represented the pride of the Royal Navy. She was designed to outrun what she could not outgun and outgun what she could not outrun. On paper, she embodied flexibility.

In practice, her thin deck armor reflected an outdated assumption: that plunging fire from long range was unlikely. When Hood encountered the German battleship Bismarck in the Denmark Strait in May 1941, that assumption proved fatal.

A single shell penetrated the deck and ignited the midship magazines. Within minutes, the ship was gone. Over 1,400 men were lost.

Hood was not destroyed by inferior engineering, but by confidence rooted in an earlier era of naval combat.

6. Bismarck: Power Without Control

The German battleship Bismarck entered service surrounded by myth. She was portrayed as unstoppable, capable of breaking Britain’s Atlantic lifeline.

Her downfall came not from a peer battleship, but from a slow, fabric-covered torpedo bomber. A single hit disabled her rudder, robbing her of maneuverability.

From that moment, the ship was no longer a weapon but a target. British forces closed in, battering her at close range until scuttling charges ended the ordeal.

Over 2,000 crew members died.

Bismarck demonstrated that even the most formidable ship can be undone by a small failure in control systems, especially when doctrine assumes invulnerability.

5. Force Z: Confidence Without Air Cover

In December 1941, Britain dispatched Force Z—Prince of Wales and Repulse—to deter Japanese expansion in Southeast Asia. The decision was based on an assumption that surface warships could operate effectively without carrier protection.

They could not.

Japanese torpedo bombers attacked repeatedly, overwhelming defenses never designed to counter sustained air assault. Within hours, both ships were lost, along with more than 800 sailors.

Force Z marked the definitive end of the battleship as an independent instrument of power. Air superiority had become non-negotiable.

4. Yamato: Scale Without Adaptation

No ship symbolized imperial ambition more than Yamato. Her armor and guns dwarfed anything afloat. She was designed to dominate surface combat.

Yet by 1945, surface combat was no longer decisive.

Sent on a one-way mission toward Okinawa with inadequate air cover and limited fuel, Yamato was swarmed by American aircraft. Bombs and torpedoes overwhelmed damage control efforts. Counterflooding failed. A catastrophic explosion ended the ship.

More than 3,000 crew members were lost.

Yamato did not fail because she was weak. She failed because she was built for a type of war that no longer existed.

3. Wilhelm Gustloff: Logistics Without Protection

The sinking of Wilhelm Gustloff remains the largest maritime loss of life in history.

Originally designed as a civilian vessel, she was pressed into service evacuating refugees from East Prussia in early 1945. Overcrowded far beyond capacity, poorly escorted, and brightly lit in contested waters, she was struck by Soviet torpedoes.

The ship capsized quickly in freezing conditions. Thousands—many of them civilians—died from exposure.

The disaster was not inevitable. It resulted from poor coordination, inadequate escort, and a failure to adapt civilian logistics to wartime conditions.

2. Shinano: Ambition Without Readiness

Shinano was the largest aircraft carrier ever built at the time, converted from a battleship hull. Rushed into service incomplete, with untested watertight compartments and poorly trained damage control teams, she sailed before being ready.

Four torpedoes from a single submarine exploited these weaknesses. Flooding spread uncontrollably. The ship capsized within twelve hours of her maiden voyage.

Over 1,000 crew members were lost.

Shinano demonstrated that scale and innovation mean little without readiness and procedural discipline.

1. USS Indianapolis: Secrecy Without Safeguards

USS Indianapolis completed one of the most consequential missions of the war, delivering components of the first atomic bomb. Afterward, she sailed alone, unescorted, through dangerous waters.

When torpedoed, the ship sank rapidly. Survivors entered the water, but no immediate alarm was raised. For days, they drifted without rescue, suffering from dehydration, exposure, and exhaustion.

Of roughly 1,200 aboard, only about 316 survived.

The failure was not mechanical. It was procedural. Tracking systems failed. Reporting protocols were ignored. Rescue was delayed because no one noticed the ship was missing.

The tragedy of Indianapolis was not simply the sinking. It was the silence that followed.

A Common Thread

These seven disasters were not identical. Some involved combat failures, others logistical collapse, others administrative negligence. But they shared a pattern.

Each reflected misplaced confidence in a single dimension of power—speed, armor, secrecy, scale—while neglecting integration, adaptability, and redundancy.

The most dangerous flaw was not steel or machinery. It was the belief that existing systems would hold under conditions they were never designed to face.

The Lesson Beneath the Waterline

Naval history is filled with innovation, courage, and sacrifice. It is also filled with reminders that no design survives first contact with reality unchanged.

Ships do not fail because their crews lack discipline or bravery. They fail when planners assume that yesterday’s logic will govern tomorrow’s fight.

The ocean does not forgive such assumptions.

In war, the most lethal flaw is not weakness, but certainty.

News

THE MYTH OF CONCRETE: Why Hitler’s $1 Trillion Atlantic Wall Collapsed in Hours During the D-Day Invasion

THE GAMBLE THAT CHANGED HISTORY: HOW D-DAY UNFOLDED FROM A DESPERATE IDEA INTO THE MOST AUDACIOUS INVASION EVER LAUNCHED By…

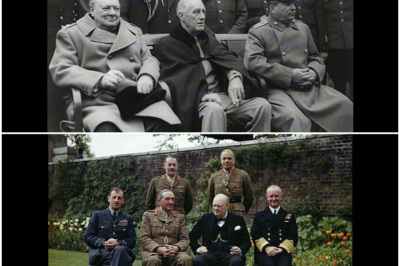

OPERATION UNTHINKABLE: The Secret WWII Plan Churchill Drew Up to Launch an Immediate Allied Attack on Stalin’s Red Army

The Secret Churchill Tried to Bury: Inside the Forgotten Plan to Strike the Soviet Union in 1945 On a bright…

THE 16-WEEK OATH: Tiny Fighter Who Weighed Less Than Water Bottle Defies Science When Father’s Heartbeat Becomes His Lifeline

THE BABY WHO ARRIVED FOUR MONTHS TOO SOON—AND THE FATHER WHO REFUSED TO LET GO An American-style narrative feature that…

The Five-Month Miracle: The Tiny Fighter Who Weighed Less Than a Water Bottle and the ‘Oxygen of Love’ That Rewrote His Fate

THE BABY WHO ARRIVED FOUR MONTHS TOO SOON—AND THE FATHER WHO REFUSED TO LET GO An American-style narrative feature that…

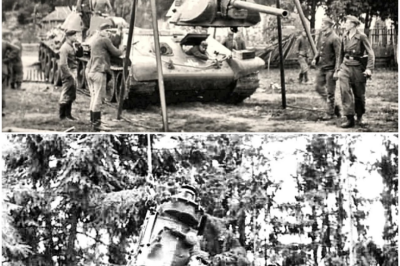

TECH PERFECTION VS. MASS PRODUCTION: Why Germany’s Complex Tiger Tanks Lost the War Against Soviet Simplicity

Steel, Snow, and Survival: How Two Tank Philosophies Collided on the Eastern Front The winter fields outside Kursk seemed to…

THE SCREAMING COFFIN: The Deadly Flaws of the Stuka Dive Bomber That Turned WWII’s Eastern Front into a Death Trap

The Fall of the Stuka: How Germany’s Most Feared Dive Bomber Became a Symbol of Vulnerability on the Eastern Front…

End of content

No more pages to load