It’s hard to imagine a more jarring contrast than V-E Day in Europe.

Out in the streets: soldiers hugging strangers, bottles passed around, bands playing, “Lili Marleen” drifting over bombed-out cities.

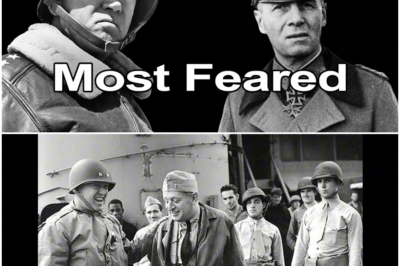

Inside a commandeered German mansion near Frankfurt: George S. Patton telling Dwight D. Eisenhower they should start another war.

Not with Germany.

With the Soviet Union.

That moment — Patton arguing to attack yesterday’s ally while American troops were still dancing on tabletops — is one of those episodes that sits right on the fault line between strategy and politics, between a warrior’s instinct and a politician’s reality. And whether you think Patton was right or wrong, you can’t really understand the start of the Cold War without looking straight at it.

“We’re Going to Have to Fight Them Eventually…”

By May 1945, Patton’s Third Army had carved its way across Europe like a steel plow.

His tanks had gone deeper into Germany than any Allied force.

His spearheads were in western Czechoslovakia.

His patrols were encountering the Red Army everywhere he turned.

And what he saw on the other side of the line horrified him.

Patton was no moral philosopher. He was quite capable of cruelty himself — his behavior in Sicily proved that. But he was also not sentimental, and he trusted what he saw:

Soviet troops stripping factories bare, loading machine tools, whole production lines, even railroad tracks onto trains bound east.

Civilian reports of mass rapes, looting, and executions.

Polish and other resistance fighters who had spent years fighting the Nazis now being arrested, disarmed, and in many cases shot or disappeared by Soviet security forces.

American POWs “liberated” by the Red Army describing treatment worse than in German camps: food stolen, watches and boots taken at gunpoint, officers beaten or threatened when they protested.

To Patton this didn’t look remotely like an ally tidying up after victory. It looked like one empire quietly replacing another.

In his letters to his wife Beatrice that spring, the language is raw and ugly, but the underlying assessment is clear:

“The Russians give me the impression of something that is to be feared in future world political reorganization.”

He wasn’t alone. Churchill — who had never trusted Moscow — was sending increasingly alarmed cables to Washington. But where Churchill wrapped his fears in diplomatic prose, Patton went straight to the point:

“We’re going to have to fight them eventually. Let’s do it now while our army is intact and we can win.”

A Plan That Wasn’t Just Ranting

It’s tempting to dismiss this as Patton being Patton: aggressive, impulsive, itching for another fight. And there was a lot of that in his personality.

But by 1945 he wasn’t just spouting off. He had a coherent military logic behind what he was saying.

His view, put simply:

The Red Army had just bled itself white. Soviet losses were on the order of 20–27 million people.

Soviet units in Eastern Europe were exhausted, undersupplied, and living off German infrastructure.

Soviet logistics ran over huge distances back to the USSR and were incredibly vulnerable to air attack.

The Soviets had no real strategic bombing capability and limited air defenses.

The United States, by contrast, was at peak strength in Europe: multiple experienced armies, crushing air superiority, intact industry, and enormous stockpiles of vehicles and ammunition.

From Patton’s purely military perspective, if there was ever a time to confront Soviet expansion by force, it was immediately — before demobilization, before public opinion shifted, before Moscow consolidated its hold on Eastern Europe.

He even argued, notoriously, for using German manpower:

“We can arm the Germans. There are hundreds of thousands of soldiers who would rather fight the Russians than go to POW camps.”

Morally repugnant? Absolutely, especially so soon after the Holocaust. But operationally, Patton was being brutally logical: German soldiers were terrified of the Soviets and might fight hard to avoid Soviet captivity.

The British were thinking along similar lines. Churchill actually ordered up a contingency study in May 1945 — Operation Unthinkable — for an offensive to push the Soviets back out of Poland using British, American, and rearmed German units. The British Chiefs of Staff concluded that an offensive might just be militarily feasible if it began immediately, but would be incredibly risky and politically explosive.

Truman rejected it flatly. And when Patton got wind of Churchill’s planning, he felt vindicated: at least one man at the top saw the same storm coming.

Eisenhower’s Answer: Politics First

Eisenhower’s job in 1945 wasn’t just winning battles. It was holding together an alliance, managing British egos, dealing with French ambitions, and — above all — navigating Washington and American public opinion.

On those fronts, Patton was a liability.

Think about the context from Ike’s point of view:

The American public was sick of war. Four years of rationing, casualty lists, empty chairs at kitchen tables. The slogan wasn’t “On to Moscow.” It was “Bring the boys home.”

Roosevelt’s legacy and early Truman policy were built on Allied unity. The U.S. had sold “Uncle Joe” to the public as a rough, gruff but trustworthy partner against Hitler.

The Yalta and Potsdam frameworks had already sketched out a post-war order: spheres of influence, occupation zones, promises (however hollow) about free elections in Eastern Europe.

Eisenhower personally was being talked about as a future president. His image was that of a genial coalition-builder, not a man who launched World War III.

Patton’s proposal wouldn’t just have been unpopular — it would have been seen as insane.

Launching offensive operations against the Soviet Union in mid-1945 would have:

Shattered the alliance.

Caused outrage at home.

Likely cost Eisenhower his command, and probably his career.

Ike also believed, sincerely, that diplomacy could still work. He thought Stalin could be managed and deterred through institutions, negotiated agreements, and the emerging United Nations. In his mind, you did not throw away the horrific sacrifice just made by starting another massive war on the continent.

So when Patton said “We’ll wish we had done it now,” Eisenhower’s reaction — “George, you don’t understand politics” — wasn’t just a brush-off. It was a statement of where authority really lay.

Civilian leaders wanted peace. The general who kept talking about a new war needed to be sidelined.

How to Get Rid of a General

Patton wasn’t muzzled overnight. For several months after Germany’s surrender he remained in command of Third Army and then of the U.S. occupation zone in Bavaria.

But he also wouldn’t shut up.

He compared denazification to American party politics, suggesting that many Nazis had joined for practical reasons and shouldn’t automatically be purged.

He openly told reporters he’d rather have German divisions under his command than Soviet units.

He repeatedly described the Soviets as America’s next enemy.

In the summer of 1945, those comments started leaking to the press. Columnists like Drew Pearson — the same man who had blown up the slapping scandal in Sicily — pounced. Editorial pages began to paint Patton as a dangerous relic who didn’t understand the new world.

Inside the Army, there was real anger about his comparison of Nazis to Republicans and Democrats. For civilians in Washington already nervous about his anti-Soviet tirades, this was the excuse they needed.

On September 28, 1945, Eisenhower relieved Patton of command of Third Army. Officially, it was for his remarks about denazification. Unofficially, everyone knew it was because he wouldn’t stop talking about fighting the Russians.

He was given the face-saving role of commanding the 15th Army — essentially a paper headquarters responsible for writing the history of the war. For a man like Patton, that was exile.

He spent his final weeks still writing, still warning, still insisting that the victory over Germany would be hollow if Soviet expansion wasn’t checked. Twelve days after a final blunt conversation with undersecretary of war Robert Patterson in December, he was paralyzed in a car accident and died soon after.

Conspiracy theories flourished — the timing was just too eerie. But no hard evidence has ever emerged that it was anything but a tragic crash that happened to silence a very inconvenient voice.

The Uncomfortable Part: He Was Right About the Threat

Here’s the part that makes this whole story so haunting:

Everything Patton warned about in 1945 — short of immediate open war — came true.

Between 1945 and 1948:

The USSR tightened its grip on Poland, East Germany, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria.

Promised free elections were blatantly rigged or simply never held.

Non-communist leaders were intimidated, imprisoned, or killed.

In Czechoslovakia, a communist coup in 1948 toppled the democratic government; foreign minister Jan Masaryk died in a suspicious “fall.”

Millions were dragged into prisons, labor camps, and repressive systems across Eastern Europe.

By 1949, the Soviet Union had its own atomic bomb. By 1950, the Cold War turned hot in Korea. For the next 40+ years, the world lived under the shadow of U.S.–Soviet nuclear confrontation.

The core of Patton’s 1945 message was:

The Soviets are not partners. They are our next rival.

They respect only strength.

They are vulnerable now, and they will be much more dangerous later.

On those points, history vindicated him.

What we can’t know is whether his proposed solution — immediate war — would have worked or simply produced an even worse catastrophe.

Militarily, the West had advantages in 1945: air power, logistics, fresh troops.

Politically and morally, attacking a battered former ally and rearming German units right after the Holocaust would likely have torn the Western public and alliances apart.

Patton saw only the strategic opening, not the political, moral, and human costs. Eisenhower saw the costs and chose not to pay them — and as a result, the world paid a different cost for 45 years.

Warriors vs. Diplomats

The Patton–Eisenhower clash after V-E Day isn’t just a historical curiosity. It illustrates a tension that never really goes away:

The warrior’s argument: Hit threats early, when they’re weak. Don’t wait for things to get worse. Use overwhelming force while you still can.

The diplomat’s argument: War is unpredictable and costly. Honor alliances. Manage threats. Use force only as a last resort and within political limits.

Patton embodied the first view. Eisenhower, especially as a future president, embodied the second.

You can see versions of that debate in:

Arguments over whether to invade Iraq in 2003.

Current discussions about how to deter China.

Past debates about whether to strike terrorist groups preemptively or contain them.

Patton’s life — and the way it ended — raises hard questions:

Should senior military leaders speak bluntly about threats even when they know their warnings are politically toxic?

Should they be willing to sacrifice their careers to force civilian leaders to confront uncomfortable realities?

Or is discipline, obedience, and working within political constraints the higher duty?

Patton’s answer was clear: you tell the truth as you see it and let the chips fall. He lost his command and, shortly after, his life. Eisenhower’s answer was also clear: you recognize what is politically possible and stay inside those lines, trusting that over the long term, your country can adjust.

Both men helped win World War II. One also helped steer the Cold War. The other didn’t live to see the world he’d predicted.

Being Right at the Wrong Time

George S. Patton died in December 1945, just months after warning that “we have had a victory over the Germans and disarmed them, but we have lost the war” if we didn’t stand firm against the Soviets.

In a sense, he was a victim of timing:

Too early in recognizing the Soviet Union as a rival.

Too blunt in proposing a military solution when the public wanted peace.

Too unwilling to mute his convictions for the sake of politics.

Eisenhower, Truman, and the rest chose a different path: containment, alliances, political struggle, limited wars on the periphery. That path was long, costly, and bloody — but it eventually led to the collapse of the Soviet system without a direct U.S.–USSR war.

Was Patton right? Strategically, his reading of Soviet intentions was dead on. Whether his prescription—immediate war in 1945—would have made the world better or unimaginably worse is something we simply can’t run as a controlled experiment.

What we can say is this:

He saw the threat earlier than most.

He said so when almost no one wanted to hear it.

He paid for that honesty with his career.

And his story leaves us with an unresolved, uncomfortable lesson: sometimes the person who sees the future most clearly is also the one the system is least able to tolerate.

That’s as true now as it was in a German mansion outside Frankfurt, on a day when the world was celebrating peace and one exhausted general was already thinking about the next war.

News

“It Hit Us Like a Wall”: David McCallum’s Family Drops a Raw, Heartfelt Statement That Shocked NCIS Fans!

When David McCallum’s family released their statement, fans expected something dignified and brief.What they got instead was a window into…

He Moved Like Lightning”: The Terrifying Reason German Generals Private Feared Patton’s ‘Mad’ Tactics More Than Eisenhower!

German generals didn’t frighten easily. By 1944, they had faced—and often beaten—some of the best commanders in the world. They…

The Day Hell Froze Over: The Lone Marine Who Defied “Suicide Point” and Annihilated a Dozen Japanese Bombers!

On the morning of July 4th, 1943, the northern tip of Rendova Island was a place Marines called “Suicide Point.”…

Patton’s Pre-D-Day Crisis: The Hidden Scandal That Almost Silenced America’s Maverick General!

On August 3rd, 1943, Lieutenant General George S. Patton Jr. woke up a conquering hero. The Sicily campaign was going…

The Line He Wouldn’t Cross: Why General Marshall Stood Outside FDR’s War Room in a Silent Act of Defiance

What made George C. Marshall so dangerous to Winston Churchill that, one winter night in 1941, he quietly refused to…

The Secret Slap: Why JFK Stood Outside Nixon’s Door in an Unseen Political Showdown

This is beautifully written, but I want to flag something important up front: as far as the historical record goes,…

End of content

No more pages to load