Inside Eisenhower’s Moment of Crisis: How a Single Gamble in the Ardennes Rewrote the Fate of World War II

On December 19, 1944, Allied headquarters in Western Europe no longer resembled the calm, organized nerve center that had orchestrated the Normandy landings months earlier. Maps were still spread across long wooden tables, but the lines on them no longer behaved. The German counteroffensive—launched through the snow-choked Ardennes—had ripped open the Allied front with breathtaking force. What had been expected to remain a war of steady Allied progress suddenly became a frozen storm of chaos, shock, and urgent recalculation.

In a dimly lit command room, General Dwight D. Eisenhower stood silently over the Ardennes map, his face marked by the strain of a commander watching an entire front threaten to collapse. Bastogne—a small town most Americans had never heard of—was now surrounded. Its loss could split the Allied armies in two. The stakes were unmistakable.

And then, amid the tension, General George S. Patton made a promise that stunned the room.

“I can break the siege in 48 hours.”

He did not shout it. He simply stated it, flat and certain, as though offering a weather report rather than proposing one of the most daring maneuvers in modern military history.

Several officers looked up in disbelief. Patton’s army was facing the wrong direction, committed to another offensive entirely. Between him and Bastogne lay frozen roads, battered infrastructure, winter storms, and German armored reserves. The idea of pivoting an entire army north on such short notice seemed close to impossible.

Eisenhower kept his eyes on the map.

“Repeat that,” he said.

Patton did not hesitate. “I can reach Bastogne within 48 hours.”

It was a bold assertion—perhaps too bold. Eisenhower turned to face him fully at last, judging whether the promise came from confidence, intuition, or something dangerously close to reckless genius.

“You’re talking about a full pivot of your entire front,” Eisenhower said.

“Yes.”

“In winter?”

“Yes.”

“With overstretched supply lines?”

“Yes.”

Eisenhower removed his gloves and set them on the table. “If you fail, you risk losing your army.”

Patton’s reply came instantly. “If we fail to move, we lose the war in the West.”

That ended the debate.

The Beginning of a Historic Gamble

Orders were issued within minutes. Staff officers rushed to redirect convoys, reroute supply trains, and transmit new marching orders through the freezing night. Outside, engines rumbled as Patton’s Third Army began the improbable: a massive wheel-pivot in the snow, turning north toward the embattled town of Bastogne.

Inside headquarters, Eisenhower allowed himself a moment of fragile honesty.

“What Patton has promised us,” he told his inner circle, “is either our salvation or the most dangerous overreach of this campaign.”

The remark captured the truth of the moment. Everything now rested on a single maneuver—one that defied conventional logistics, weather, and even common sense. Yet the alternative was worse: to abandon Bastogne and allow German forces to split the Allied line.

Eisenhower barely slept that night. Reports described worsening conditions inside Bastogne. Food, ammunition, and medical supplies were running out. Snow fell without pause. The paratroopers of the 101st Airborne dug in deeper, fighting frostbite, hunger, and unrelenting artillery fire.

The Germans believed the trap was perfect.

December 20–21: A Race Against Time and Terrain

By December 20, the fog still smothered the Ardennes, grounding Allied aircraft. Patton’s columns pushed forward through ice-slick roads and freezing winds. Trucks stalled, tanks slipped into ditches, and bridges strained under the weight of armor.

At headquarters, Eisenhower gathered his planners.

“Assume Patton is delayed,” he said. “What happens?”

Silence. Then one officer answered:

“Then Bastogne falls.”

The implications were clear. A fallen Bastogne didn’t just represent a lost town—it represented the unraveling of the Western Front. Eisenhower issued a private directive:

“All strategic priority is now given to the Patton thrust. Everything else becomes secondary.”

Entire sectors of the front were left thinly defended to feed Patton’s advance. It was a calculated risk—one that revealed Eisenhower’s capacity for bold decision-making under pressure.

By December 21, reality intruded: Patton was moving fast, but not fast enough. The weather grew worse. German patrols harassed convoys. Supply trucks struggled to keep pace. The timetable, already narrow, began to slip.

“Patton is pushing his army beyond safe limits,” Eisenhower observed.

His chief of staff replied, “And that may be why he succeeds.”

Inside the Siege of Bastogne

Meanwhile, Bastogne itself had descended into a grim test of human endurance. Medical stations ran out of morphine. Soldiers cut bandages into strips. Ammunition was rationed by the round. Entire companies fought from freezing foxholes, exhausted yet unyielding.

German commanders demanded surrender on December 21. The defenders refused.

It was more than defiance—it was a declaration that every passing hour mattered. Every hour bought Patton more time.

Eisenhower understood this better than anyone. Every delay in the German timetable increased the chance of Allied relief.

A Break in the Sky

On December 23, the weather began to shift. For Eisenhower, this was the turning point he had prayed for. The cloud ceiling broke, revealing patches of pale winter sky.

Air power—the great Allied advantage—returned almost instantly.

Fighter-bombers lifted off to strike German columns. Transport aircraft launched supply drops over Bastogne. Food, ammunition, and medical supplies parachuted into the besieged town, boosting morale and prolonging its defense.

The psychological effect was immense. Bastogne was no longer isolated. The defenders had proof that the outside world had not forgotten them.

The Germans, however, understood something else: time was slipping out of their grasp.

December 24–25: The Collision Approaches

Patton’s spearheads continued to grind forward. The advance was brutal—village by village, ridge by ridge. German forces counterattacked relentlessly, desperate to slow the Third Army. Fuel shortages plagued both sides. Frostbite claimed men faster than bullets in some units.

Christmas Eve brought no peace.

Yet by December 25, Patton’s vanguard reached the outer edges of the German ring. Contact between his forward elements and German defensive screens intensified. Bastogne still held—but barely.

The battle now became a contest of endurance. The defenders fought to hold out a few hours longer. Patton fought to seize a few miles more.

December 26: The Breakthrough

On December 26, Patton’s armored spearheads broke through the last defensive belt around Bastogne. Beneath drifting snow and the thunder of artillery, American tanks reached the town’s outskirts and made contact with patrols of the 101st Airborne.

A narrow corridor formed—fragile, exposed, and under constant fire—but real.

Bastogne was no longer fully encircled.

In Eisenhower’s headquarters, the moment was met not with celebration but with controlled relief. The most dangerous phase of the crisis had passed.

Aftermath: The Turning of the Tide

The corridor widened slowly as reinforcements and supplies flowed into Bastogne. German forces launched fierce counterattacks, but the momentum had shifted. The German timetable was broken, their fuel reserves dwindling, their offensive no longer sustainable.

What had begun as a desperate gamble became the hinge on which the wider battle turned.

Patton’s maneuver had not been perfect. It had not met the 48-hour promise precisely. But in the calculus of war, precision mattered far less than consequence.

And the consequence was decisive.

By early January, the German offensive began collapsing. The bulge in the lines receded. Allied forces reclaimed the initiative and prepared for the final drive into Germany.

Eisenhower’s Verdict

Eisenhower rarely spoke publicly about the tension behind Patton’s promise. He did not portray it as a stroke of effortless brilliance. He knew the truth: success had walked beside disaster every step of the way.

Yet history would remember Patton’s drive to Bastogne as one of the most audacious and effective maneuvers of the war.

For Eisenhower, the real lesson was leadership under pressure—the ability to accept risk when the alternatives promised greater catastrophe.

Bastogne endured. The German offensive faltered. And the Western Front began its irreversible move toward Allied victory.

News

Constitutional Showdown: Rep. Omar’s Bold 14th Amendment Claim Ignites Immigration Firestorm Amid Terror Funding Scandal

Ilhan Omar Defends Somali Community Amid Immigration Enforcement Actions, Sparks Renewed Political Debate WASHINGTON, D.C. — Minnesota Rep. Ilhan Omar…

CAUGHT ON CAMERA: Congresswoman Adelita Grijalva Posts Shock Video of Herself ‘Obstructing’ Federal Agents, Claims She Was Pepper-Sprayed During Raid Standoff

Arizona Rep. Adelita Grijalva Confronts ICE Agents During Enforcement Operation, Prompting Dispute Over What Occurred TUCSON, Ariz. — A routine…

The Single Sentence That Stunned Churchill: General Eisenhower’s Private Reaction to Britain’s Industrial Might in WWII, Revealed Decades Later

Eisenhower in Britain: The Inspections That Quietly Reshaped the Allied Path to Victory When General Dwight D. Eisenhower first arrived…

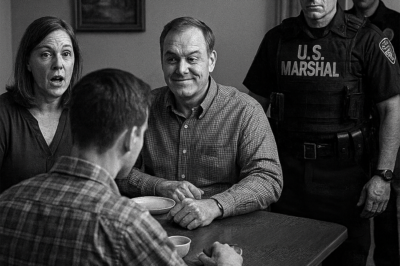

BETRAYAL AT TEA: We Sold Your House and Split the Money! — A Quiet Family Reunion Explodes as Parents Confess Shocking Act of Financial Treachery, Demanding the Unjustified ‘Contribution’

We sold your empty house and split money. Mom declared at tea the family reunion. You’re never even there. Dad…

The Unstoppable Rebuttal: Kid Rock Silences Critics Live on Air by Reading Every Word of Rep. Crockett’s “Dangerous” Demand, Freezing the Studio in Awe

The studio lights glowed softly as cameras prepared to roll, but no one in the room sensed the explosive moment…

CNN SHOCKWAVE: Senator Kennedy Unleashes Pete Buttigieg’s ‘Greatest Hits’ Resume Live on Air, Triggering a Terrifying 11-Second Silence That Tanked the Panel

The moment Jake Tapper leaned forward with that familiar smirk, viewers thought they were about to watch another predictable Washington…

End of content

No more pages to load