My name’s Harold. I’m seventy-two. Retired postman, bad knees, and the kind of hands that shake when I hold a coffee cup too long. I don’t own a smartphone. Never will. But I know how to write.

Last winter, after our church bulletin board got locked up “for liability reasons,” I hammered a piece of plywood onto the bus stop shelter and wrote at the top in thick black marker:

First note I pinned up was from me: “I sharpen knives. Free. Just knock.”

Within a week, it filled.

Mrs. Torres, eighty-three, wrote: “Need leaves raked. My back hurts.”

Two kids on bikes scribbled: “We’ll do it after school.”

A single mom posted: “Free babysitting swap. I cook, you watch the baby.”

A veteran in dirty boots taped up: “Hungry. Don’t need cash. Just a hot meal.”

I watched strangers—people who hadn’t looked each other in the eye for years—start talking again. Pies exchanged for plumbing work. Teenagers mowing lawns instead of hiding in their rooms. Folks leaving phone numbers, sometimes just first names. No apps, no passwords. Just paper and pens.

Then came the note that broke me:

“Lost my job. Two kids. Anybody know of a room? — Lisa.”

By morning, someone else had scribbled: “We have a basement. Warm. Safe. Come by.”

That story made the local Facebook group. Half the town called it beautiful. The other half called it dangerous. “You’ll get scammed.” “Strangers in our homes.” “Why not use an app? At least apps track people.”

I answered the way I always do: “Not everyone has Wi-Fi. But everyone has a neighbor.”

Two weeks later, a city truck pulled up. Men in reflective vests. A clipboard. One of them read out loud: “Unregulated postings. Risk of exploitation. Must remove.”

I stood there shaking, not from age this time, but from rage. “That wall fed a veteran last night,” I told them. “That wall kept two kids from sleeping in a car. Is kindness illegal now?”

They didn’t answer. Just started unscrewing the bolts.

But something happened. People came. First the two kids with rakes. Then Mrs. Torres with her walker. Then Lisa with her children. Then others—Black, white, Latino, immigrants, rich, broke, tattooed, suited. They all carried scraps of paper in their hands.

Each one walked up and taped their note right over the men’s hands.

“He fixed my sink.”

“She watched my son.”

“I wasn’t hungry last night because of this wall.”

Dozens of voices, dozens of shaky notes. The city crew froze.

Then the police chief arrived, slow stride, heavy belt jangling. For a second I thought it was over. He read the order, read the wall, read the faces staring back. Finally, he sighed. “There are laws for safety,” he said. “But if a law bans people from being neighbors, maybe the law is wrong.”

The workers packed up. The wall stayed.

Now every bus shelter in town has one. Messy. Coffee-stained. Some notes ripped by rain. But alive. Breathing.

I’m no hero. I just wrote the first note. The rest was people choosing each other when the world said not to.

So next time someone tells you America is too divided, too cold, too selfish—think of a wall covered in shaky handwriting, where a veteran got fed, a mother found a home, and two kids learned raking leaves matters.

We don’t fix the world with apps or arguments.

We fix it with a piece of plywood, a pen, and the courage to say: “I see you. I’m here.”

News

SCANDAL LEAKS: Minnesota Fraud Case Just ‘Exploded,’ Threatening to Take Down Gov. Walz and Rep. Ilhan Omar

Minnesota Under Pressure: How a Wave of Expanding Fraud Cases Sparked a Political and Public Reckoning For decades, Minnesota enjoyed…

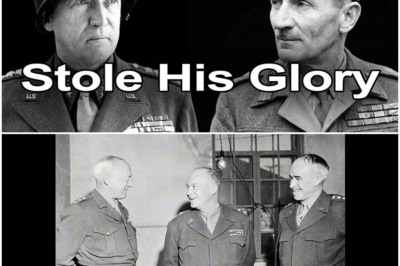

FROZEN CLASH OF TITANS’: The Toxic Personal Feud Between Patton and Montgomery That Nearly Shattered the Allied War Effort

The Race for Messina: How the Fiercest Rivalry of World War II Re-shaped the Allied War Effort August 17, 1943.Two…

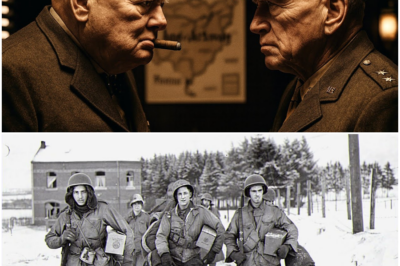

THE THRILL OF IT’: What Churchill Privately Declared When Patton Risked the Entire Allied Advance for One Daring Gambit

The Summer Eisenhower Saw the Future: How a Quiet Inspection in 1942 Rewired the Allied War Machine When Dwight D….

‘A BRIDGE TO ANNIHILATION’: The Untold, Secret Assessment Eisenhower Made of Britain’s War Machine in 1942

The Summer Eisenhower Saw the Future: How a Quiet Inspection in 1942 Rewired the Allied War Machine When Dwight D….

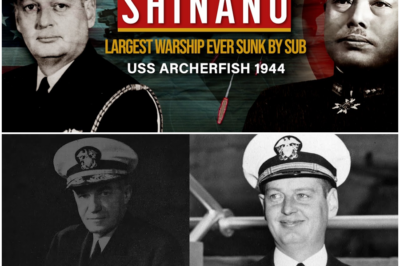

THE LONE WOLF STRIKE: How the U.S.S. Archerfish Sunk Japan’s Supercarrier Shinano in WWII’s Most Impossible Naval Duel

The Supercarrier That Never Fought: How the Shinano Became the Largest Warship Ever Sunk by a Submarine She was built…

THE BANKRUPT BLITZ: How Hitler Built the World’s Most Feared Army While Germany’s Treasury Was Secretly Empty

How a Bankrupt Nation Built a War Machine: The Economic Illusion Behind Hitler’s Rise and Collapse When Adolf Hitler became…

End of content

No more pages to load