George C. Marshall and the Burden of D-Day: What Leadership Really Costs

In most telling of World War II, the story of D-Day is a story of courage and clarity. Ships shoulder to shoulder in the Channel, aircraft filling the sky, soldiers stepping off landing craft into surf and fire — and behind it all, a confident Allied high command, executing a plan that would change the course of the war.

But for George C. Marshall, the U.S. Army’s Chief of Staff and one of the chief architects of Allied victory, D-Day was something else as well: a moral weight that never entirely lifted.

In his lifetime, Marshall earned a reputation for restraint. He rarely raised his voice. He avoided self-promotion. He refused to keep a diary because he believed private notes could be misinterpreted or exploited. After the war, when journalists and historians came knocking, he answered carefully and briefly.

And yet, in his later years, Marshall allowed a few unsettling hints to slip through the armor. Hints that suggest D-Day was not just an extraordinary military success, but also the moment when, in his words, “the line between truth and necessity disappeared.”

What did he mean by that? And what does it tell us about what real leadership in wartime actually costs?

The Quiet Architect of Victory

George Catlett Marshall was not a battlefield general in the usual sense. While Patton, Bradley, and Eisenhower moved across maps in Europe and North Africa, Marshall was stationed in Washington, D.C., orchestrating a global war.

As Army Chief of Staff from 1939 to 1945, he oversaw the expansion of the U.S. Army from a small peacetime force into a multi-million-man machine capable of fighting on two major fronts. He chose which commanders rose and which did not. He weighed conflicting British and American proposals. He argued, often alone, for a direct cross-Channel invasion of France long before it was fashionable or politically comfortable.

Others collected headlines. Marshall collected responsibilities.

After the war, he did something rare for a general: he became more famous for what he built in peace than for what he won in war. As Secretary of State, he proposed the European Recovery Program — soon known to the world as the Marshall Plan — a massive effort to help rebuild Western Europe’s shattered economies and prevent the political chaos that often breeds extremism. In 1953, he became the first career soldier to receive the Nobel Peace Prize.

To the public, he seemed like the embodiment of order and balance: the calm voice that had guided the U.S. through crisis and then helped shape a more stable world.

But those closest to him noticed something else. Even in quiet retirement at his home in Leesburg, Virginia, there were moments when Marshall would pause mid-conversation, as if tugged backward in time by thoughts he chose not to share. When the talk turned to D-Day, he grew particularly careful.

Leadership, he once said, “demands silence where others expect words.” With D-Day, that silence was deliberate.

Why Marshall Didn’t Command D-Day

There was a time when almost everyone in Washington assumed that George Marshall would command the Allied invasion of France. He had the seniority, the trust of Roosevelt, the respect of the British.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt reportedly even asked him directly if he wanted the job.

Marshall’s answer was characteristic: he refused to ask for it.

He believed it was improper for a senior officer to seek a particular command. The decision, he insisted, belonged to the president alone. Roosevelt eventually concluded that he needed Marshall in Washington more than he needed him in Europe. The job of Supreme Commander went instead to Dwight D. Eisenhower, a general whom Marshall himself had identified and promoted.

To many, this looked like self-denial, perhaps even a missed opportunity. But Marshall’s own notes, preserved in his papers, hint at something more complex. He wrote that the invasion would “demand of its commander more than any man should be asked to bear.” He understood what was coming: not just a difficult battle, but a convergence of moral and strategic pressures unlike any in modern history.

By stepping aside, Marshall avoided the direct spotlight of Overlord. But he did not avoid its burdens. From Washington, he remained deeply involved in the planning, the logistics, the deception operations, and the overall risk calculations. He became, in effect, the invasion’s architect who chose not to stand on the balcony when the curtain rose.

Deception, Secrecy, and Half-Told Truths

One of the least glamorous but most decisive elements of D-Day was deception.

Under the umbrella title “Operation Bodyguard,” Allied planners mounted a sprawling campaign of misdirection. Inflatable tanks, dummy landing craft, fake radio networks, and carefully controlled leaks convinced the German high command that the invasion would likely hit the Pas-de-Calais area, the shortest route across the Channel.

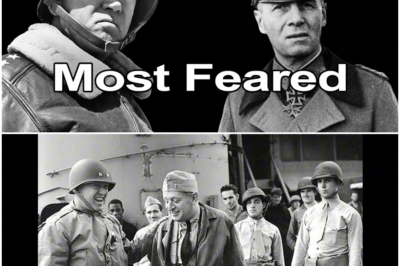

The boldest part of that deception — Operation Fortitude — conjured an entire phantom army in southeast England. Its supposed commander was General George S. Patton, the very man the Germans most feared. The “First U.S. Army Group” had camps, vehicles, and command posts that existed largely on paper and in the imagination of German intelligence.

The Germans believed what they were meant to see. When the real invasion landed at Normandy on 6 June 1944, powerful German units remained tied down near Calais, waiting for an attack that never came.

To historians, Bodyguard and Fortitude are triumphs of wartime creativity. To Marshall, they were also something else: necessary lies.

He approved the compartmentalization that kept many Allied officers in the dark about the broader picture. He backed strict controls on who knew what and when. He enforced a rule that “loose talk” was not simply careless — it could be deadly.

Years later, when someone asked him whether the level of secrecy had ever troubled him, he answered with a sentence that lingered uneasily in the air:

“You cannot conduct a war and tell the whole truth at the same time.”

That remark can be read simply as a statement of fact about operational security. Yet in the context of his later comments, it suggests something more: Marshall understood that deception had extended inward as well as outward. The enemy was misled — but so, to a degree, were the men going ashore.

“We Sent Some Men to Certain Death”

The most unsettling lines attributed to Marshall about D-Day come from his final years, when his health was failing but his mind remained sharp.

In private conversations with researchers and military historians, he again returned to Normandy — but not to celebrate it.

He spoke instead of “operational truth divided.” Of men “briefed under assumptions that could not all be met.” Of specific sectors of the landing — historians often cite Omaha Beach as the prime example — where planners understood that casualty rates might be extremely high, perhaps even prohibitive, but accepted those risks in order to preserve the larger plan.

In one recollection, he is quoted as saying that senior planners knew “some units were unlikely to survive intact” and that “we accepted that certain beaches would draw fire so others could break through.”

He summarized it with a sentence as cold as it was honest:

“We sent some soldiers to certain death.”

On one level, this is not surprising. All serious planners understood that any invasion of heavily fortified shores would be costly. Everyone knew D-Day would bring terrible losses. But Marshall’s phrasing suggests something more targeted — the recognition that deception and secrecy, which protected the operation as a whole, also prevented some of the men involved from fully understanding the dangers they were walking into.

To be clear, there is no evidence that Marshall or anyone else deliberately “sacrificed” a specific unit in the sense of writing men off casually. The records do not support lurid conspiracy theories. What they do show is something more uncomfortable but more ordinary in war: leaders accepting lethal risks for some to give the best chance of success for many.

Marshall himself later called the level of secrecy and compartmentalization “bordering on cruelty.” He admitted that “men would die believing they were part of one plan when in truth they were pawns in another.” That language is unusual for him. It hints at a moral discomfort he never resolved publicly.

A General Haunted by His Own Success

After the war, Marshall rarely spoke about Normandy in detail. When he did, his emphasis was on the soldiers, not the planners. He praised their courage. He downplayed his own role.

It was in his post-war work that the inner tension became most visible.

As Secretary of State, he presented his European Recovery Program not just as an economic measure, but as a moral one. The purpose of the Marshall Plan, in his own understated words, was not just to rebuild bridges and factories, but to prevent “desperation from requiring desperate measures again.”

To those who knew him well, that sounded like a man trying to balance a ledger.

Where D-Day had required secrecy, the Marshall Plan required openness — public commitments, transparent aid, and cooperation instead of deception. Where victory on the beaches had depended on calculated risk and partial truths, his peace-time policy depended on restoring trust and stability.

In a private note found among his papers, he wrote: “The purpose of peace is to balance what victory could not justify.” That line has rarely been quoted, but it may be one of the most revealing sentences he ever wrote.

What Marshall’s “Terrifying Truth” Means for Us

So what, exactly, was the “terrifying truth” George Marshall carried from D-Day to his grave?

It was not a hidden scandal or some secret plot waiting to be “uncovered.” It was something both simpler and more disturbing:

That even in a just war, even in a necessary battle like D-Day, victory may depend on decisions that cannot be fully explained, and on partial truths told to those who must do the hardest fighting.

Marshall’s late-life comments don’t overturn what we know about the Normandy invasion. They don’t diminish the courage of the men who fought or the importance of liberating Europe from Nazi rule. What they do is complicate the story.

They remind us that:

Deception can be both brilliant and morally costly. Operation Fortitude saved lives by keeping German divisions away from Normandy — but it also meant some Allied units faced stronger defenses than they had been led to expect.

Secrecy protects operations and hurts individuals. The fewer people knew the whole truth, the safer the plan — but the harder it was for those involved to understand their true role.

Leadership can require silence. Marshall believed that a commander must sometimes carry knowledge he cannot share. That burden is not dramatized in war movies, but it may be one of the hardest aspects of command.

Peace is not just an absence of war, but a chance to correct what war could not. Marshall’s work after 1945 suggests he saw reconstruction as a kind of moral counterweight to the compromises war had forced.

When we celebrate D-Day, we rightly honor courage, sacrifice, and the turning of the tide against tyranny. But Marshall’s reflections invite us to see more: the moral strain behind the planning, the private doubts of those at the top, and the lingering question of how much truth leaders can or should tell in the middle of an existential fight.

George C. Marshall was not a man of dramatic confessions. He never wrote a tell-all memoir. He never sought to shock or scandalize. Even his most candid remarks are measured, almost hesitant. But the fact that a man so disciplined in speech chose, near the end of his life, to say that D-Day forced him to send some men to “certain death” — and that secrecy “bordering on cruelty” was part of the price — should give us pause.

It doesn’t mean we were wrong to fight. It doesn’t mean the invasion was unjustified. It does mean that even the most necessary wars leave behind unresolved questions — about how victory is achieved, and what it does to the people who have to make the decisions no one else can.

Marshall once said: “The only victories worth remembering are the ones that don’t require silence afterward.”

He spent the second half of his life trying to build a world where such victories might be possible. That effort — as much as any battle he helped plan — may be his truest legacy.

News

The Iron Ladies Strike Back: Key Republican Women Are Openly Launching A Scorching Revolt Against Speaker Johnson!

WASHINGTON — When Mike Johnson won the gavel last fall, many House Republicans hailed the soft-spoken Louisianan as a unifier…

“It Hit Us Like a Wall”: David McCallum’s Family Drops a Raw, Heartfelt Statement That Shocked NCIS Fans!

When David McCallum’s family released their statement, fans expected something dignified and brief.What they got instead was a window into…

Patton’s Final Prophecy: The Chilling 1945 Demand to Attack Stalin That Eisenhower Dismissed!

It’s hard to imagine a more jarring contrast than V-E Day in Europe. Out in the streets: soldiers hugging strangers,…

He Moved Like Lightning”: The Terrifying Reason German Generals Private Feared Patton’s ‘Mad’ Tactics More Than Eisenhower!

German generals didn’t frighten easily. By 1944, they had faced—and often beaten—some of the best commanders in the world. They…

The Day Hell Froze Over: The Lone Marine Who Defied “Suicide Point” and Annihilated a Dozen Japanese Bombers!

On the morning of July 4th, 1943, the northern tip of Rendova Island was a place Marines called “Suicide Point.”…

Patton’s Pre-D-Day Crisis: The Hidden Scandal That Almost Silenced America’s Maverick General!

On August 3rd, 1943, Lieutenant General George S. Patton Jr. woke up a conquering hero. The Sicily campaign was going…

End of content

No more pages to load