The late-night landscape was always a battleground of wit and sharp commentary, where the comedians who sat at the desk each night had the power to shape public discourse, to challenge the status quo, and to make us laugh while doing it. For years, Stephen Colbert had been the reigning king of this kingdom. His Late Show was a vehicle for political commentary, a place where humor and satire could pierce through the noise of the day’s events and offer a much-needed reprieve. But for Bill Maher, sitting across from Dave Rubin in the dimly lit studio of Club Random, that world had become something far less inspiring.

Maher, known for his biting critiques of both sides of the political spectrum, had never been one to shy away from controversy. Yet, the conversation that night took a turn that many had not seen coming—his candid assessment of Colbert’s role in the late-night realm would shake the very foundation of comedy on TV. The gloves were off, and Maher was prepared to speak the uncomfortable truth.

With his usual bluntness, Maher declared, “He’s nothing. He’s also very successful. But he’s just giving the machine what it wants all the time.”

Dave Rubin, ever the provocateur, leaned in, a smile playing at the edge of his lips. “That’s well said. Giving the machine what it wants. I wish I’d thought of that phraseology.”

The phrase “the machine” seemed to hang in the air like a fog, its meaning only becoming clearer as Maher elaborated. The machine, in Maher’s view, wasn’t just a corporate entity—it was the entire system that governed mainstream comedy and media. It was the vast, invisible network that determined who got the platforms, the budgets, and the voice to shape the national conversation. In Maher’s eyes, Colbert had become the perfect cog in that machine, a performer who had learned to navigate the system’s demands with precision.

“Colbert was given a job as a corporate comic on a ridiculously massive platform,” Maher explained. “A show with a hundred-million-dollar budget. Do you know what we could do with $100 million? Instead, they lose $40 million a year—but why was he given the job? Because he’ll do what the machine wants.”

Rubin nodded, soaking in Maher’s words, his expression one of deep understanding. “Whether Colbert knows it or not, he was just giving the machine what it wants,” he said, a hint of sorrow in his voice.

For Maher, Colbert was a reflection of a disturbing trend in late-night television—the rise of the “corporate comic.” Where once these late-night hosts were known for their sharp, unpredictable humor, they now seemed to be interchangeable parts, all reading from the same corporate script, all towing the same narrative lines. The rebellious edge, the defiance against the status quo, was gone. What had once been a sanctuary for the free-thinking, irreverent comedian had become a place where advertisers, corporate interests, and network executives held the strings.

Maher’s critique wasn’t just about Colbert’s style or his show—it was about the very nature of the business. Late-night television, once a bastion of irreverence, had been swept up in the tides of corporate influence. Instead of pushing boundaries, hosts like Colbert were now expected to embrace the agendas handed to them by the network. Maher pointed to one moment in particular that encapsulated this shift: “Dancing to convince people to get a vaccine that doesn’t work whenever the corporate agenda demands.”

Maher’s words were harsh, but they struck a chord. The COVID-19 pandemic had created a time of heightened political division, and late-night hosts like Colbert were often at the frontlines, playing a role in shaping public opinion. But in Maher’s view, that wasn’t enough anymore. The authenticity of these shows had been stripped away, replaced with something far more sanitized. The need to entertain and inform had been sidelined in favor of appeasing the corporate sponsors and maintaining a smooth, non-controversial narrative.

“There’s a growing sense among viewers that late-night comedy has lost its edge,” said Dr. Sharon Klein, a media analyst who had been following the rise of the corporate comic. “The hosts are less comedians, more corporate spokespeople. Audiences are noticing—and they’re tuning out.”

But Maher and Rubin were not only lamenting the loss of the old days; they were advocating for something new. They argued that true authenticity in comedy now required independence. In their eyes, the only way for a comedian to remain genuine was to step outside the corporate system, to risk less promotion and fewer resources, but to speak freely without being bound by the constraints of the machine.

“Going independent really is the only thing you can do if you’re going to be a truly honest player in the space,” Rubin said, his voice tinged with urgency.

Maher, ever the disruptor, agreed. “I’m interested in the corporate layer of it. The people running the show saying, ‘Okay, we’ll give you this to do this.’ It’s all orchestrated.”

But how much longer could this system persist? According to Maher, the age of edgy, unpredictable comedy—the kind that resonated with audiences because it felt real—might be coming to an end. In its place was a more sanitized, corporate-friendly format designed to placate advertisers and large media conglomerates. And as Maher pointed out, that shift wasn’t just happening on The Late Show—it was happening across the entire late-night landscape.

“It’s the inherent problem,” Maher concluded, his tone somber. “Not everyone will give the machine what it wants.”

As the conversation wound down, both Maher and Rubin emphasized the importance of independent voices in comedy. They argued that the future of late-night television might lie in smaller, more niche platforms, where creators could bypass the corporate giants and deliver real, unfiltered content to an audience hungry for authenticity. But that kind of content came with risks: fewer resources, less promotion, and a much harder climb to success.

For Maher, this conversation wasn’t just about Colbert—it was about the very soul of late-night television. He lamented the loss of the sharp, critical comedy that had once defined the genre. What had once been a space for challenging the establishment, for pushing boundaries, had become a polished, corporate-friendly spectacle.

And as Maher’s critique of Colbert echoed through the media, viewers were left to wonder: Is this the end of an era for late-night television? Or will the machine continue to churn out its sanitized version of comedy, leaving the raw, real voices of independent creators to fight for their place on the fringes?

In the coming months, the question will only grow more pressing. Will Stephen Colbert respond to the growing criticism? And, more importantly, will the world of late-night television ever return to its rebellious roots, or is it destined to remain a corporate playground for the foreseeable future? Only time will tell.

News

The ‘Suicide’ Dive: Why This Marine Leapt Into a Firing Cannon Barrel to Save 7,500 Men

Seventy Yards of Sand: The First and Last Battle of Sergeant Robert A. Owens At 7:26 a.m. on November 1,…

Crisis Point: Ilhan Omar Hit With DEVASTATING News as Political Disasters Converge

Ilhan Omar Hit with DEVASTATING News, Things Just Got WAY Worse!!! The Walls Are Closing In: Ilhan Omar’s Crisis of…

Erika Kirk’s Emotional Plea: “We Don’t Have a Lot of Time Here” – Widow’s Poignant Message on Healing America

“We Don’t Have a Lot of Time”: Erika Kirk’s Message of Meaning, Loss, and National Healing When Erika Kirk appeared…

The Führer’s Fury: What Hitler Said When Patton’s 72-Hour Blitzkrieg Broke Germany

The Seventy-Two Hours That Broke the Third Reich: Hitler’s Reaction to Patton’s Breakthrough By March 1945, Nazi Germany was no…

The ‘Fatal’ Decision: How Montgomery’s Single Choice Almost Handed Victory to the Enemy

Confidence at the Peak: Montgomery, Market Garden, and the Decision That Reshaped the War The decision that led to Operation…

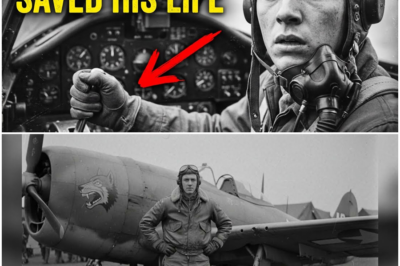

‘Accidentally Brilliant’: How a 19-Year-Old P-47 Pilot Fumbled the Controls and Invented a Life-Saving Dive Escape

The Wrong Lever at 450 Miles Per Hour: How a Teenager Changed Fighter Doctrine In the spring of 1944, the…

End of content

No more pages to load