In the middle of a rain-soaked street, a scarred biker’s blood hit the pavement as he clutched a child’s inhaler rescued from the gutter. People saw danger in him—but that night, he became the only reason a little boy could breathe.

The sirens didn’t come for us that night; they slid past the complex like a snake, and my boy’s breaths got small and sharp as pins.

It was just past two in the morning.

My hands still smelled like burned coffee and fryer grease.

I was a waitress at Hank’s 24-Hour, the chrome-and-neon kind of place that caught every lonely thing rolling down our strip of highway.

The eviction notice was taped to our door with blue painter’s tape and somebody’s indifference.

Past-due, past-hope, past-pride.

Jonah coughed through it like paper.

He was seven and carried his inhaler like a little pistol.

We’d stretched the last refill by prayer and silence.

Insurance had lapsed when I chose rent over a premium.

I broke the seal on the door and carried Jonah inside, set him on the thrift-store couch, turned the fan to high like wind alone could sweep oxygen out of thin air.

He wheezed, eyes glassy.

“You’re okay,” I lied.

We were not.

That was when the Harley rolled up, engine low and alive, like thunder trying to behave.

The headlight cut a white tunnel through the stairwell grating.

He killed the engine and the night folded in, thick and hungry.

I knew him from the diner.

He came in on dead hours.

Never ate.

Ordered coffee black.

Never took off his gloves.

I called him Hawk because of the thin white scar that curved under his eye and the way he watched the door, the booths, the exits, like a bird from a fence post.

He wore a leather cut that had lived.

I’d seen men straighten when he stepped out to smoke.

He scared the loud ones back into quiet.

He scared me a little too.

He took off his helmet, shook rain from it, and stood in the hallway with his hands open and empty.

“I heard the cough from the street,” he said.

“You can hear it through the brick if you’ve learned to listen.”

“I’m fine,” I said too quick.

He looked past me.

Jonah made a small, thin whistle that sounded like a balloon dying.

Hawk stepped inside in three careful beats, like approaching a wounded thing.

He knelt, his knee creaking, leather popping, and put an ear near my boy’s mouth.

“Where’s his spacer?” he asked.

I stared.

“You know inhalers,” I said.

“Too well,” he said.

“My brother died in a cornfield with a blue one in his pocket.

Ambulance got lost.

Everybody thought the wheeze was just a ‘calm down’ thing.

I learned the sound like my own name.”

He stood and scanned our apartment.

Two chairs.

Couch.

A pile of bills like snowdrifts.

A milk crate of toys.

His eyes landed on the taped notice.

He didn’t say anything to shame me.

“Night clinic?” he asked.

I nodded.

“No money for the visit,” I said.

He grabbed his helmet and tossed it to me.

“Put him on,” he said.

“I’ll ride slow.”

“I can’t—” I said.

“You can,” he said quietly.

“You’ll hold him behind me.

Your knees will find the place to tuck.

If you fall, you fall with me.

But he won’t stop breathing on my watch.”

In the parking lot, he lifted Jonah as if he weighed a loaf of bread.

He strapped my boy to him with a thick bungee, then put my arms around both of them.

Leather smelled like rain and gasoline and something older, like cedar and smoke.

We slid through town like a rumor.

Walmart’s pharmacy light glowed like a chapel.

The clinic inside had a sign that said “Closed.

See Hospital After Hours.”

The hospital was ten miles.

Hawk parked under the blue “PICKUP” sign, kicked the stand, and pulled out his wallet.

He had photos tucked behind a military discharge card that he shut before I had time to read the name.

“Wait here,” he said.

He walked into Walmart like a storm with a plan.

I rocked Jonah and counted his ribs.

A patrol car rolled by and slowed.

The officer inside looked at us and kept going.

When Hawk came back, he wasn’t carrying medicine.

He was empty-handed and there was a new quiet in his face.

“Pawn shop’s still open,” he said.

“They know me.”

Across the lot, a pawn shop blinked a red neon guitar into the wet night.

I followed him inside under a bell that sounded like a warning.

It smelled like old carpet and nickel and stories that went bad.

Hawk laid his cut on the glass.

He unstitched the bottom rocker patch with thick fingers that trembled at the seams.

The clerk took it in two careful hands.

“Man,” he said softly.

“You sure?”

Hawk nodded like swallowing a bone.

He set a small velvet bag on the counter.

Chrome pipes rested inside like polished bones.

“Vintage,” the clerk said.

“Pre-ban.”

Hawk didn’t answer.

“Cash quick,” he said.

“For a kid.”

The clerk looked at Jonah, then at me, then back at Hawk.

He counted out bills like respect.

News

SCANDAL LEAKS: Minnesota Fraud Case Just ‘Exploded,’ Threatening to Take Down Gov. Walz and Rep. Ilhan Omar

Minnesota Under Pressure: How a Wave of Expanding Fraud Cases Sparked a Political and Public Reckoning For decades, Minnesota enjoyed…

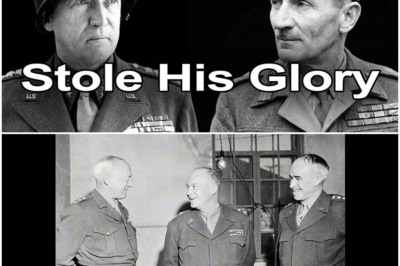

FROZEN CLASH OF TITANS’: The Toxic Personal Feud Between Patton and Montgomery That Nearly Shattered the Allied War Effort

The Race for Messina: How the Fiercest Rivalry of World War II Re-shaped the Allied War Effort August 17, 1943.Two…

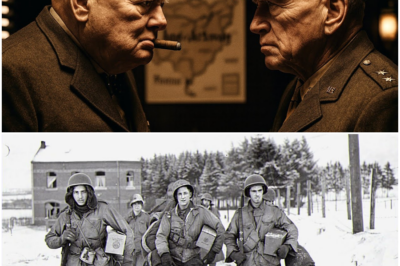

THE THRILL OF IT’: What Churchill Privately Declared When Patton Risked the Entire Allied Advance for One Daring Gambit

The Summer Eisenhower Saw the Future: How a Quiet Inspection in 1942 Rewired the Allied War Machine When Dwight D….

‘A BRIDGE TO ANNIHILATION’: The Untold, Secret Assessment Eisenhower Made of Britain’s War Machine in 1942

The Summer Eisenhower Saw the Future: How a Quiet Inspection in 1942 Rewired the Allied War Machine When Dwight D….

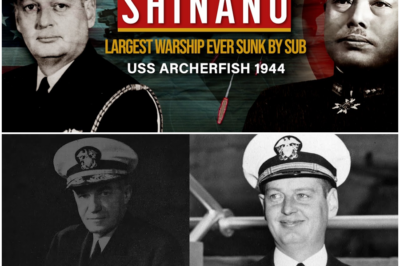

THE LONE WOLF STRIKE: How the U.S.S. Archerfish Sunk Japan’s Supercarrier Shinano in WWII’s Most Impossible Naval Duel

The Supercarrier That Never Fought: How the Shinano Became the Largest Warship Ever Sunk by a Submarine She was built…

THE BANKRUPT BLITZ: How Hitler Built the World’s Most Feared Army While Germany’s Treasury Was Secretly Empty

How a Bankrupt Nation Built a War Machine: The Economic Illusion Behind Hitler’s Rise and Collapse When Adolf Hitler became…

End of content

No more pages to load