The Night the Bombers Disappeared: How a Forgotten Scientist Changed the Air War Over Europe

Shortly before midnight, the sky over northern Germany vibrated with a sound that had become grimly familiar by 1943. Hundreds of Royal Air Force bombers pushed eastward through darkness, engines synchronized, crews silent and tense. Inside the lead Lancaster, radar operator Flight Lieutenant Derek Jackson watched his glowing screen, bracing for the moment he had learned to fear more than any other.

German radar defenses were awake.

For months, those green radar lines had spelled near-certain danger. Heavy anti-aircraft batteries, guided by precise radar tracking, and night fighters scrambled from multiple airfields could reduce a bomber force by six percent or more in a single mission. Statistics ruled the air war: an average bomber crew could expect to survive only about eleven missions. Completing a full tour of twenty-five was almost unimaginable.

Yet on this night, something was different.

As the bomber stream crossed the coast, German radar operators saw not hundreds of aircraft, but tens of thousands of signals blooming across their screens. The clear formations dissolved into chaos. Anti-aircraft guns fired blindly. Searchlights swept empty sky. Night fighters chased targets that vanished as soon as they approached.

By the early hours of morning, Hamburg was ablaze. Of the 791 bombers dispatched, only twelve failed to return. The loss rate—about 1.5 percent—was astonishing.

The weapon that changed everything was not a new aircraft, a faster engine, or a heavier payload. It was something far simpler: thin strips of aluminum foil, cut to precise lengths, bundled into small packets and thrown into the air.

The British called it Window. The Americans would later call it chaff. And behind it stood a scientist whose name remained largely unknown for decades.

A Crisis in the Air

By early 1942, the Allied bombing campaign was in trouble. German radar systems such as Freya and Würzburg could detect incoming aircraft well before they reached their targets, directing anti-aircraft fire with alarming accuracy. Night operations offered only partial relief. Losses remained severe, and morale within Bomber Command was fragile.

Senior leaders confronted a grim reality. At current rates, the bomber force would bleed itself dry. Training pipelines could not replace experienced crews fast enough. Without sustained air pressure, German industry would remain largely untouched, enemy fighter forces would stay concentrated elsewhere, and any future invasion of Europe would become vastly more difficult.

Every proposed solution fell short. Flying higher reduced bombing accuracy. Jamming signals proved temporary. Tighter formations only made aircraft easier to track.

The war in the air demanded a radical idea.

An Unlikely Breakthrough

At the Telecommunications Research Establishment on England’s southern coast, a young physicist named Joan Curran was working in a small countermeasures section. She had studied physics at Cambridge, graduating with honors—yet received no degree, because the university did not formally grant them to women at the time.

She lacked the credentials and status that typically commanded attention in Britain’s scientific hierarchy. What she did have was curiosity and persistence.

During routine experiments measuring how different materials reflected radar signals, Curran tested narrow strips of metal. The results were startling. A single lightweight strip produced a radar return comparable to that of a large bomber.

The explanation was elegant physics. When a metal strip is cut to half the wavelength of a radar signal, it resonates. Instead of merely reflecting energy, it absorbs and re-emits it efficiently, creating a powerful return. German radar systems operated at known wavelengths, which meant strips could be cut to precise lengths for maximum effect.

Dropped in large numbers, these strips could create dense clouds of false targets. Real aircraft would disappear into the background noise.

Curran built prototypes using ordinary aluminum foil, refining dimensions, packaging, and dispersal methods. Her calculations suggested that replacing a small portion of a bomber’s payload with these strips could overwhelm enemy radar completely.

The idea worked—almost too well.

A Dangerous Solution

Field tests confirmed Curran’s findings. Radar operators could not distinguish aircraft from false returns. Loss reductions of more than seventy percent appeared achievable.

Yet success triggered fear.

British leaders realized that if Window could blind German radar, it could do the same to Britain’s own defenses. Coastal warning systems, naval protection, and night fighter control all relied on radar. Releasing the technology risked revealing it to the enemy, who could then copy and deploy it in retaliation.

The debate became deeply divisive. Some argued that Window was too dangerous to use at all. Others countered that refusing to act guaranteed continued losses.

In mid-1942, the decision went against Curran. Window was banned from operational use. Production halted. Existing supplies were locked away. Her invention sat in warehouses while bomber crews continued to face deadly odds.

Curran did not stop working. She refined the system quietly, improving durability and deployment methods, and repeatedly submitted updated reports. Each month, losses mounted. Each month, her data showed how many lives might have been saved.

The Turning Point

Pressure finally came from across the Atlantic.

As American forces intensified daylight bombing in 1943, their losses grew severe. When U.S. commanders learned of Window’s existence—and its suppression—they reacted with disbelief. The logic of withholding a proven defensive measure became harder to justify as casualty lists lengthened.

A critical meeting brought senior military leaders face to face with Curran’s data. She presented numbers calmly: current loss rates, projected crew survival, and the statistical certainty that Window could dramatically alter the balance.

The debate was fierce. But one question cut through the argument: how long could the bomber offensive survive without change?

The answer was not long.

In July 1943, authorization was finally granted. Window would be used.

Hamburg and the Proof

The first large-scale deployment came during raids on Hamburg later that month. Crews were briefed on an unusual addition to their load. Every minute, packets of Window were to be released from the aircraft.

As the strips dispersed, German radar screens filled with echoes. Anti-aircraft fire lost precision. Night fighters struggled to identify real targets. The effect was immediate and dramatic.

Losses dropped exactly as Curran had predicted.

Over subsequent raids, the pattern held. Operations that once would have cost dozens of aircraft now saw only minimal losses. In one week alone, more than a hundred bombers—and hundreds of aircrew—were saved.

German forces quickly recovered samples and understood the principle. They began developing their own version. But adapting radar systems to counter the deception took time. During that crucial window, the Allies gained a decisive advantage.

Beyond the Bombing Campaign

Window’s influence extended far beyond bomber protection. In June 1944, it played a key role in the deception operations preceding the Normandy landings. Carefully deployed chaff clouds created the illusion of invasion forces moving toward the wrong coastline, drawing enemy attention away from the true landing sites.

The success of these operations bought critical hours for Allied troops establishing a foothold in France.

By war’s end, radar countermeasures had become a permanent feature of modern warfare. The basic principle Curran demonstrated—creating false electronic targets to confuse detection systems—remains in use today, refined but unchanged in concept.

A Quiet Legacy

Despite the impact of her work, Joan Curran received little public recognition during her lifetime. Official histories emphasized more prominent figures. Honors were scarce. Her name rarely appeared in popular accounts.

Decades later, she received an honorary doctorate—her first formal academic recognition. She accepted it modestly, emphasizing teamwork rather than individual achievement.

Curran passed away in 1999. By then, chaff had become so ubiquitous that few paused to ask who had first imagined it.

Yet among those who flew through hostile skies in the darkest years of the war, the legacy was deeply personal. For many, those strips of aluminum meant survival, a return home, a life lived beyond the cockpit.

Sometimes the most powerful ideas are not loud or complex. Sometimes they are light enough to float on the wind—and strong enough to change history.

News

The Führer’s Fury: What Hitler Said When Patton’s 72-Hour Blitzkrieg Broke Germany

The Seventy-Two Hours That Broke the Third Reich: Hitler’s Reaction to Patton’s Breakthrough By March 1945, Nazi Germany was no…

The ‘Fatal’ Decision: How Montgomery’s Single Choice Almost Handed Victory to the Enemy

Confidence at the Peak: Montgomery, Market Garden, and the Decision That Reshaped the War The decision that led to Operation…

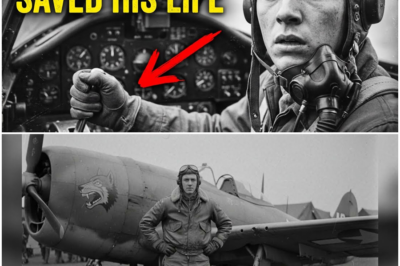

‘Accidentally Brilliant’: How a 19-Year-Old P-47 Pilot Fumbled the Controls and Invented a Life-Saving Dive Escape

The Wrong Lever at 450 Miles Per Hour: How a Teenager Changed Fighter Doctrine In the spring of 1944, the…

The ‘Crazy’ Map That Could Have Changed Everything: How One Japanese General Predicted MacArthur’s Secret Attack

The “Crazy Map”: The Japanese General Who Predicted MacArthur’s Pacific Campaign—and Was Ignored In the spring of 1944, inside a…

The Silent Grave: 98% Of Her Crew Perished in One Single Night Aboard the Nazi Battleship Scharnhorst

One Night, One Ship, Almost No Survivors: The Mathematics of a Naval Catastrophe In the winter darkness of December 1943,…

Matt Walsh Unleashes Viral Condemnation: “Just Shut the F* Up” – The Daily Wire Host Defends Erika Kirk’s Grief*

Matt Walsh Defends Erika Kirk Amid Online Criticism Following Husband’s Death WASHINGTON, DC — Conservative commentator and Daily Wire host…

End of content

No more pages to load