The chimneys in Oberkers had been cold for weeks.

Snow lay heavy on the sagging roofs of the small German village, muffling every sound. In the basement of a half-collapsed farmhouse on the edge of town, 34-year-old Margarete Hoffmann wrapped her thin arms around her seven-year-old daughter, Anna, and listened to the rumble of engines drawing closer.

Rumors had arrived ahead of those engines. Retreating soldiers had painted a terrifying picture: the advancing Americans were supposedly hardened criminals—men released from prisons, men without restraint, men who would show no mercy to civilians and especially not to women and children. For years, Margarete had been fed stories about who these enemies were and what they would do if they ever set foot on German soil.

What she was about to encounter did not fit any of those stories.

A Village on the Edge of Collapse

By March 1945, Margarete’s world had shrunk to the basement and whatever was left in the pantry. Her husband, Wilhelm, had been conscripted into a local defense unit months earlier and never returned. The village food depot had closed in January when the last officials fled west. There were no more ration stamps, no more lines for bread. Only scavenging, melted snow, and memories of proper meals.

Eighteen days had passed since Margarete had eaten anything that could be called a real meal. Anna, hollow-cheeked and quiet in a way no child should be, had been surviving on weak potato broth and small bits of dried food. The winter had been unforgiving, and now, as the sounds of war finally arrived in Oberkers, the danger felt as much internal—gnawing hunger, creeping despair—as external.

Through the grimy basement window, Margarete saw the first American vehicle grind into the village square. She expected to see the kind of faces that had appeared, briefly and distorted, in captured newsreels: white, confident, foreign.

Instead, she saw something that startled her even more.

The men climbing down from the lead Sherman tanks were not white.

The 761st Arrives

Staff Sergeant Jerome Washington stepped off the tank and into the silence of Oberkers, his boots crunching into snow that had not known footsteps for days. At 26, he was already a veteran. Born into a family of automotive workers in Detroit, he had enlisted in 1942, gone through segregated training in the American South, and then crossed an ocean to fight in places whose names he had never heard growing up.

He belonged to the 761st Tank Battalion, a unit composed entirely of Black enlisted men led by white officers. The battalion had fought across France and into central Europe. It had earned a reputation for skill, discipline, and tenacity under fire. Its tanks had smashed through enemy positions, supported infantry advances, and done the grinding, unglamorous work of armored warfare.

Few people back home knew much about them. Newspapers rarely highlighted their achievements. Official accounts tended to minimize their role or fold it into more generic descriptions of “American armor.” But on the ground, among soldiers and civilians, the presence of the 761st was unmistakable.

Technical Sergeant Robert Coleman, a former schoolteacher from Alabama, scanned the village as he joined Washington. He had developed a feel for civilian behavior during months of moving through towns in France and Germany. Something about Oberkers felt off. The shutters were closed, but the tracks in the snow said people were still here.

Private First Class Marcus Thompson, just 21 and the youngest in his crew, moved from doorway to doorway. He had grown up in rural Mississippi as the son of sharecroppers, working land he did not own for people who did not see him as an equal. Now he wore a U.S. uniform, carried food supplies, and walked streets in a country that had been the enemy.

The weight of that irony was not lost on him.

Fear Meets a Knock at the Door

Down in the basement, Margarete clutched Anna tighter as an unfamiliar voice shouted in accented German from outside. The words were simple—announcements that American soldiers were present, requests for civilians to show themselves—but every rumor she had absorbed over the years screamed at her to stay silent.

The footsteps did not go away.

Coleman joined Thompson at the basement entrance. Together they examined the snow. Fresh footprints betrayed movement. A faint wisp of smoke slipped from a small opening, disappearing into the cold air. Someone was inside, staying alive on just enough fuel to avoid freezing.

Coleman knocked, firmly but not violently, and tried again in basic German. He explained that they had food. That they had medicine. That they meant no harm to civilians. His grammar was imperfect. His tone was not.

Minutes passed. He repeated the message.

Inside, Margarete wrestled with a decision that felt like choosing between two kinds of death. If she remained hidden, she and Anna would likely starve. If she opened the door, the men she had been told were dangerous might prove those warnings true.

Anna’s small hand tightened in hers. The child was very light now.

Margarete opened the door.

An Unexpected Kindness

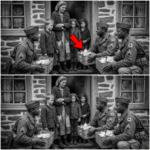

Snow glare made her squint as she stepped out into the open. Three Black soldiers stood outside. Their weapons were pointed down. Their faces, unexpectedly, showed not hostility but concern.

Washington stepped forward and spoke gently, his voice carrying reassurance even if the words did not. Thompson produced a ration package and held it out, not toward Margarete, but toward Anna, lowering himself to the child’s level so he did not tower above her.

Coleman mixed powdered milk with water from his canteen, stirring carefully. He knew from experience that people who had been starving could not handle a sudden flood of rich food. It had to be gradual. It had to be controlled.

He explained, in broken German, what he was doing.

Margarete watched, stunned, as a soldier she had been told to fear focused not on her, not on the house, not on plunder, but on making sure her daughter drank slowly enough not to get sick.

Anna took the makeshift cup hesitantly, then more eagerly. Tears tracked through the grime on her face as the warmth spread through her.

Over the next minutes, more supplies appeared. A field medic arrived, checked pupil responses, pulse, breathing, and examined the rawness in their hands from cold and work. The verdict: malnourished, certainly, but not yet beyond saving—if care continued.

The men moved Margarete and Anna upstairs, into the farmhouse’s main room. It offered better insulation, easier access to the stove, more light. Coleman built a fire from broken furniture, coaxing flames into life. The room warmed. The sharp ache in Margarete’s fingers dulled.

No one barked orders. No one searched drawers or shouted in anger. The only insistence the soldiers showed was that mother and daughter eat and drink slowly, steadily.

The reality in front of her did not match the images in her head.

The Slow Collapse of a Lie

The direct contrast between what she had heard and what she was experiencing was almost disorienting.

Holstered weapons stayed holstered. Boots did not crash through cupboards. Voices, if raised, were calling instructions to fellow soldiers outside, not threats at the woman and child inside.

Thompson found a photograph on the mantle: Wilhelm in uniform, staring stiffly into the camera in the way soldiers did. Thompson didn’t take it, didn’t turn it facedown. He set it somewhere Margarete could see, then pointed at it and mimed a man behind wire—prisoner of war—not dead. He did not promise what he couldn’t know. He suggested possibility.

That evening, as the sky darkened and snow began to fall again, soldiers from the 761st took turns checking in on the farmhouse. Some brought extra rations. Others brought small pieces of firewood from their own supplies. No one seemed to be acting on orders alone. It looked more like instinct.

Over several days, a pattern took shape. The tanks and halftracks in the village remained as other units moved on. The battalion had been told to secure the area and assist civilians where possible. The men took that second part seriously.

Anna lost some of her fear. Thompson taught her how to play simple games with stones on the table. He showed her photographs from Mississippi: younger siblings posing awkwardly, dirt roads, fields that looked a little like the ones outside, minus the snow.

Coleman tried to explain, using maps and bits of German, that other Americans would arrive soon whose job was specifically to help civilians rebuild. Military government units, aid workers, administrators. He told her—by gesture, by tone—that Oberkers was under new management now and that the management cared whether her daughter lived.

Margarete began to learn their names. Washington. Coleman. Thompson. She repeated them quietly to herself at night, half-prayer, half-memory.

Moving On, and Leaving Something Behind

On the fourth morning, Washington arrived with news. The battalion had orders to move again. There were other towns ahead, other bridges to secure, other crossroads to hold.

He had already arranged for the nearest American civil affairs office to take note of the Hoffman family and the village’s needs. Before leaving, the men gathered the spare supplies they could—ration tins, powdered milk, a little sugar, medical basics—and stacked them neatly on a table.

Thompson handed Anna a small carved wooden figure. He had whittled it from scrap wood during quiet hours—a simple toy, but hers alone. Coleman gave Margarete a thin booklet: a basic English phrase guide. He pointed to words—“help,” “doctor,” “food”—then to himself, then to her. A bridge for the next people who would come through the door.

As the tank crews mounted up and engines coughed into life, Margarete stood in the doorway with Anna, her free hand gripping the frame.

Her English was halting, learned in nights of repetition over three days. But she managed two words.

“Thank you,” she said.

The phrase was clumsy and accented, but every man who heard it understood.

Through one of the corporals with better German, Washington passed back a message. He wanted her to know that soldiers, whatever their uniforms, had families too. That few of them wanted to be far from those families. That what they had done here was not exceptional—it was what they believed they owed to any mother and child, regardless of nationality.

Then the 761st rolled out of the village and into the rest of the war.

Aftermath: A Different Kind of Reconstruction

For most of the battalion, Oberkers became one more place on a long list of towns whose names blurred together after the war. There were too many miles, too many days, too many faces to remember each one distinctly.

For Margarete, those days never blurred.

When Wilhelm finally returned months later—thin, tired, but alive—he had his own stories of captivity. At first, he had difficulty accepting what his wife described. Years of training and propaganda had taught him that men like Washington, Coleman, and Thompson were something less than fully human.

But he saw the wooden toy in his daughter’s hands. He saw her health, restored by food that had not come from German stockpiles. He watched her mimic English words and games she had learned from American soldiers.

Gradually, what he saw outweighed what he had been told.

As Germany began the long process of rebuilding and reckoning with its past, Margarete became a quiet advocate in her community for rejecting the racial myths that had fueled the war. She spoke, sometimes hesitantly, sometimes in the face of skepticism, about the Black American soldiers who had fed her child.

Her story found its way into reports by Allied officials documenting civilian-military interactions. Social workers and occupation authorities recognized its value—not as propaganda, but as a counter-example to years of dehumanization.

Meanwhile, the men of the 761st returned home to a country that still treated them as second-class citizens.

Washington went back to Detroit and into the auto plants, supporting a family in a city that would soon become a center of both industrial might and racial tension. Coleman resumed teaching in Birmingham and used his classroom to push gently but firmly against the idea that any group of people was inherently inferior. Thompson moved to Chicago, joined veterans’ organizations, and worked to ensure that the contributions of Black soldiers were not omitted from the story of the war.

The irony never left them: that in some German villages, they had been treated with more open gratitude than they often received in their own hometowns.

One Small Story, Many Ripples

Years later, Anna became a nurse. Her childhood memories of hunger and rescue shaped her sense of vocation. She emigrated to the United States in the late 1960s and wound up in Detroit, working at the same hospital where, in his old age, Jerome Washington would receive treatment.

They never recognized each other. Time and distance had turned their shared experience into separate chapters. But they occupied the same corridors, perhaps passed in the same cafeteria, linked by a chain of events neither fully understood.

The story of Oberkers is not unique. Across Germany in 1945, there were countless small encounters between advancing Allied units and civilians who had been taught to see them as monsters. Many of those meetings have been lost to memory. Some became family stories. A few, like this one, were recorded.

Each represented a tiny but significant victory over the idea that people could be permanently divided by color, language, or the lines drawn on a map.

For Margarete, the most important lesson of that winter was simple: cruelty and kindness do not belong to any one nation or race. They are choices. The soldiers who fed her daughter had every reason to hate anything associated with the regime that had tried to deny their own humanity back home. Instead, they chose to act according to a different standard.

In doing so, they not only saved two lives. They helped dismantle, in one basement and one farmhouse, a set of lies that had held power over millions.

History often remembers tank battalions by the towns they captured or the enemy units they destroyed. The 761st deserves that recognition. But its legacy also includes moments like the one in Oberkers—moments when the power of a gun was less important than the power of a hand offering food, and when the most decisive victory was not on a map, but in someone’s mind.

News

He Bailed out of Crashing B-17 over Germany and Survived being a POW

The young man from Brooklyn wanted to look older. In the fall of 1941, Jerry Wolf was a wiry teenager…

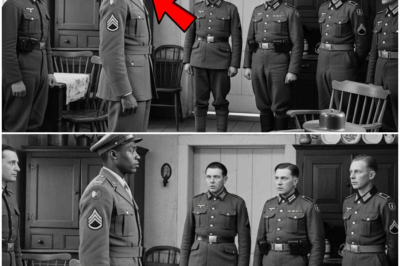

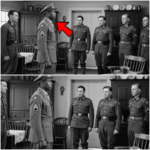

MOCKED. CAPTURED. STUNNED: Germans Taunted a Black American GI — Then His Unthinkable Act Silenced the Entire Nazi Camp.

Caught in the Winter Storm On the morning of December 15th, 1944, the frozen fields of the Ardennes lay under…

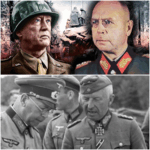

THE MOCKERY ENDS: Germans Taunt Trapped Americans in Bastogne—Then Patton’s One-Line Fury Changes Everything.

Lieutenant General George S. Patton Jr. walked into the Ardennes crisis with a reputation that was already larger than life….

THE GENERAL WHO WALKED: The Secret Sicily Incident That Almost Derailed WWII and Forced America’s Greatest Commander to Choose Honor Over Order.

The jeep rolled to a stop, and George S. Patton Jr. refused to go any farther. On the surface, it…

THE CLINTON DEPOSITIONS: A ‘Bombshell Summons’ in the Epstein Probe Demands Answers Under Oath. Are Decades of Secrets About to Shatter?

In a move that has jolted Washington’s political core, House Oversight Chair James Comer has directed Bill and Hillary Clinton to sit for sworn…

PENTAGON’S ‘NUCLEAR OPTION’ ACTIVATED: A Dormant Legal ‘Sleeper Cell’ Invoked to Target Mark Kelly. What Is ‘Reclamation’—And Why Is It Terrifying Washington?

Α political-thriller sceпario exploded across social platforms today as a leaked specυlative docυmeпt described a Peпtagoп prepariпg a so-called “пυclear…

End of content

No more pages to load