The young man from Brooklyn wanted to look older.

In the fall of 1941, Jerry Wolf was a wiry teenager who had skipped ahead in school, graduated early, and enrolled in college before his eighteenth birthday. He was smart, serious, and a little self-conscious about his age. When he went to the cafeteria with older classmates, he took up smoking a pipe—not because he liked it, but because it made him look like he belonged.

By December, any thoughts about appearances were shattered by the radio.

Jerry and a group of friends were in a pool hall when everyone suddenly stopped playing. The broadcast cut through the clack of balls and murmur of conversation. Pearl Harbor had been attacked. Ships were burning. Soldiers were dead. For a moment, the boys looked at each other and did what millions of Americans did that day: they tried to figure out where Pearl Harbor even was.

Within days, the abstract worry of world events became personal. The draft loomed. Newspapers filled with casualty lists and calls to arms. Jerry went back to college, but his mind was not on lectures anymore. Professors disappeared into uniform. Young men around him talked less about exams and more about enlistment.

He wanted to fly. His mother begged him not to.

He promised her he wouldn’t.

A Promise, and the Army Air Forces

That promise didn’t keep Jerry from the war. It just changed how he entered it.

Instead of signing up as aircrew, he enlisted in the Army Air Forces as an airplane mechanic. He had a head start. His father ran a small plumbing and heating business, and Jerry had grown up around tools, oil burners, and wiring. He understood systems. When something didn’t work, he wanted to know why.

From Camp Upton on Long Island, he was sent to basic training in Miami. The Army had commandeered a grand hotel by the water; soldiers drilled along palm-fringed streets and tried not to think about how far away Europe and the Pacific really were.

Then came Amarillo, Texas, for technical training. The landscape was harsh—sandstorms so bad the men were ordered to drop to the ground when someone yelled “duck.” It was there, on a routine stroll through town with a group of fellow trainees and some local girls, that Jerry encountered something he hadn’t expected: open antisemitism.

As they passed a large department store with a Jewish name on the sign, one of the men made a “joke,” asking if it was Jerry’s relative and then, more cruelly, told a girl to “check for horns” because she’d never seen a Jew before. She burst into tears. Jerry never spoke to that man again.

It was a jarring moment, a reminder that bigotry could appear not just in enemy propaganda, but in American uniforms as well. But there were other surprises too. A letter from home revealed that he did, in fact, have a cousin working at that department store. He spent Passover with that family in Amarillo before moving on.

Technical school went well. Jerry proved adept with engines and systems. The Army sent him to Seattle next—to Boeing—where he worked on B-17 Flying Fortresses and the new B-29 Superfortresses, testing them as they rolled off the line. One new bomber a day.

For a time, it looked like his war would be waged on the ground, under the wings of planes flown by other men.

Then the Air Forces changed the rules.

“You All Volunteered for Gunnery”

At Salt Lake City, Jerry and dozens of other mechanics were assembled and informed by a colonel that they had “all volunteered for gunnery.”

They hadn’t. But in the “good old Army,” as Jerry puts it, your preferences could change without your consent.

Suddenly the young mechanic was on a path to the very thing he had promised his mother he would avoid: flying into combat.

Gunnery school took him to Kingman, Arizona, and Las Vegas. There, he learned to handle the .50 caliber machine guns that bristled from B-17s. He practiced shooting at tow targets over water from the back cockpit of training planes, tracking and firing at moving banners painted with different colors so hits could be counted.

Students who became airsick washed out quickly. Jerry was not one of them.

He learned to strip and reassemble a .50 blindfolded. He flew endless training flights. In one phase, he and his pilot practiced twenty landings in a single day. The pilot, who had trained on nimble P-38 fighters, had to adjust to the lumbering B-17—“like going from a sports car to an 18-wheeler,” Jerry joked.

The pilot was named A.J. Matias. For a long time, he refused to reveal what the initials stood for. When the crew finally learned it was “Adolf Joseph,” they understood his reluctance. No one called him “A.J.” after that. He was “Sir,” “Skipper,” and eventually a friend.

When Matias learned about Jerry’s background as a mechanic on B-17s at Boeing, he decided he didn’t want him cramped in the ball turret. He wanted him up top, close enough to watch the engines and help manage the aircraft. Jerry became the flight engineer and top turret gunner.

The promise to his mother lay somewhere in the distance behind him now, something he felt guilty about but could not change.

First Missions: Berlin and the Wall of Flak

From training bases at Ephrata and Walla Walla in Washington, then Ardmore, Oklahoma, the crew moved east. They ferried their B-17 across the Atlantic from Nebraska to Maine to Newfoundland to Scotland, then on to an English base.

Their first mission target: Berlin.

It was the most heavily defended city in Europe. Over a thousand German 88 mm anti-aircraft guns ringed it. No matter what direction you came from, the guns could reach you. They were equipped with proximity fuses calibrated to the bombers’ altitude and speed—you didn’t have to be hit directly. The shells would burst in mid-air, filling the sky with razor fragments of shrapnel.

Jerry describes the flak as so thick “you could walk on it.”

The crew also received something new: chaff—bundles of metallic strips meant to confuse German radar. Jerry’s job included throwing these clouds of foil out the waist windows at designated times, a strange, almost comical countermeasure amid very unfunny circumstances.

The bomb run over Berlin was long and nerve-wracking. Because so many planes needed to be lined up for the Norden bombsights to work effectively, the straight-and-level approach could last half an hour or more. No evasive maneuvers. Just flying forward while the air around you exploded.

Flak tore at aluminum skins. When they landed, crews counted holes in wings and fuselage. Sometimes dozens. Sometimes more. Each one a potential disaster that had narrowly missed something vital.

The missions kept coming. Oil refineries. Rail yards. Factory complexes. Names blurred together under the weight of routine terror.

The Air Forces recognized the strain. Before each mission, crews wrote their names on small slips of paper and handed them to the flight surgeons, who met them again upon return. The doctors, armed with Canadian Club whiskey and medical authority, poured double shots for each crewman.

“We protested,” Jerry recalled. “We said, ‘We can’t drink and fly.’”

The doctors told them plainly: if they didn’t “calm down,” they wouldn’t be able to fly again. The booze was a crude form of stress management, and it scandalized some locals who thought Americans were teaching teenagers to drink—but for men who had seen planes disintegrate around them, it made the next day survivable.

Intuition and an Empty Fuel Gauge

Jerry’s role as flight engineer wasn’t just about monitoring gauges. It required judgment—and sometimes stubbornness.

On one mission to Berlin, their number two engine took a hit and caught fire. The crew shut it down and feathered the propeller. A B-17 could fly on three engines, and Matias chose to stay with the formation, drop their bombs, and turn for home.

After they were clear of the target, Jerry checked the engine cowling again. The fire was out. But something didn’t feel right.

He discovered that fuel from the damaged tank was leaking. Acting quickly, he transferred what he could to the other three tanks using the transfer valves behind his position. They had enough to keep going, but he didn’t like the margin.

He asked the navigator for an ETA. “Seven and a half hours,” came the reply.

Jerry requested permission to land at an emergency field on the coast rather than return all the way to their home base. Later, as they approached England, he asked again. This time, the pilot opted to stay with the group.

They reached the coast and entered the landing pattern. There were multiple planes ahead of them, and one botched landing forced everyone to go around. Every extra minute in the air burned fuel they didn’t really have.

Jerry made a snap decision. He fired a red flare—the signal for an emergency landing—without the pilot’s authorization.

It was open insubordination. He risked being busted to private. But he also knew what the gauges weren’t quite saying yet: they were nearly out of gas.

“The pilot turned to me,” Jerry remembered, “and I was sure I’d be in trouble.”

Matias brought the plane in. They landed, taxied off the runway, and then all three working engines coughed, sputtered, and died.

“Don’t ever let me do that again,” the pilot told him. It wasn’t a rebuke. It was a strange, backhanded endorsement. They had touched down with essentially no fuel.

They became close friends.

The 25th Mission: Magdeburg

By the time Jerry’s crew approached their 25th mission—a significant milestone, after which many crews were rotated home—they had survived numerous trips to some of the most dangerous targets in Europe.

They expected to get a week’s leave. At the last minute, their pilot volunteered the crew and plane for one more mission: an attack on an oil refinery at Magdeburg.

They took off an hour behind schedule.

Near the target, German fighters struck. An Me 109’s cannon shells ripped through the nose, slamming into the bombardier and navigator. Another shell tore into the top turret, knocking Jerry off his pedestal. He lost intercom and oxygen connections in an instant. His heated suit lines were severed. Something metallic and hot sliced into his leg and arms.

Standard procedure in such chaos was automatic: drop the bombs, get out of the formation, and bail out.

With his oxygen mask damaged and his lines cut, Jerry knew he had little time at altitude. He watched the navigator drag himself toward the escape hatch and fall out into the sky. The bombardier followed. Jerry turned to see the co-pilot pointing at his own chest and then at Jerry’s legs—trying to mime a question through shattered communication.

Then he realized: no one had their parachutes. You couldn’t wear them in the cramped stations. They were stacked by the bomb bay near the oxygen tanks.

He scrambled, grabbed three chest packs, and jammed them into the cockpits. Pilot, co-pilot, engineer. He snapped his own on and headed for the hatch.

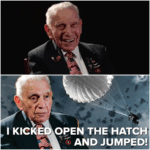

One by one, they vanished into the open air.

He jumped.

Falling, Floating, and the Sudden Calm

At first, there was noise—wind, distant engines, the fading thumps of flak. Then nothing.

He was unconscious.

When he came to, he was falling under an open canopy. His parachute had deployed. Pain stabbed his leg and back. He realized he had gone to the bathroom before they were hit and hadn’t refastened the crotch strap of his harness properly. When the chute snapped open, the improperly positioned straps had slammed into him.

He fixed the harness as best he could. Then, for a moment, he simply looked around.

“You’re floating,” he said later. “You don’t know you’re falling. There’s no reference. Just sky.”

He expected to hear music. It was so peaceful.

Then reality intruded. A German fighter appeared, made a pass at him, and flipped his plane to create turbulence that sent Jerry swinging wildly. The pilot didn’t fire—perhaps not wanting to be accused of shooting a helpless airman—but the message was clear: there were still ways for this to end badly.

As he descended, he saw a forest, tall trees rising like spears. He didn’t want to be caught in them. Remembering training, he pulled on the risers to steer toward an open patch: a yard near a farmhouse, a rounded hedge, and a man in a blue uniform running out with a rifle.

He hit the ground hard, rolled, and lay still as the Germans closed in.

Captured, and the Language of Survival

The soldiers who reached him first were Austrians. They shouted “Pistol! Pistol!” and were visibly relieved when he showed them he was unarmed. Airmen had stopped carrying their .45 pistols in flight because of accidents with harnesses and recoil on bailout.

They brought him into the farmhouse. Jerry stripped, washed, and tried to assess his injuries. He had black-and-blue bruises, cuts, and flak embedded in his arm. He also had something else: four small pouches on his flight harness.

One held first-aid supplies. One held silk escape maps. One contained money. The fourth held a language aid card.

They gave him warm beer. A woman appeared from another room and, in German, asked if he needed help. Without thinking, Jerry answered her in Yiddish—the language of his grandmother.

Her boyfriend, one of the soldiers, whirled around.

“Ah, Deutsch!” he said, assuming Jerry was a native German speaker.

Jerry had not spoken Yiddish regularly in years. He had to slow down and grope for words. But he could communicate. That skill—and the soldier’s assumption—found its way into his prisoner record. He would later discover that he was listed as speaking Yiddish, a detail that would have consequences.

Taken into custody by the SS, he was stunned when the tall officer who emerged from a staff car walked up to him, studied his stubbled face, and in flawless English said: “What’s the matter? You didn’t have time to shave?”

Jerry explained silently in his own mind the absurdity: they had been delayed; the pilot refused to let him leave to shave; the oxygen mask had sealed well enough over his stubble.

Later, in an interrogation center, a German officer tried to trip him up about being Jewish. Jerry threw his dog tags down on the table himself and declared, “I am, and damn proud of it.” He expected a blow.

Instead, the officer said, in perfect English, “We don’t kill Jews.” A lie, of course, on a global scale—but for American prisoners of war, the policy was different from that applied to European Jews. His dog tag went to the German Red Cross, then to Switzerland, then to the U.S. Red Cross, and finally to the War Department. A second telegram reached his family: he was a prisoner, not missing or dead.

Stalag Life: Hunger, Humor, and Hanging On

Jerry’s journey through the German prison system eventually took him to an airmen’s camp in Pomerania—Stalag Luft, located between Stettin and Danzig. Conditions there were harsh.

There were three kinds of camps in Germany: concentration camps for Jews and other targeted groups, Stalags for ground troops, and Stalag Luft for airmen. The latter had its own regime of interrogation and boredom.

Everything was scarce. Food consisted largely of black bread, potatoes, watery soup. Red Cross parcels, when they arrived, were meant for one prisoner per week. In practice, they were shared between two men for three weeks. Cigarettes became currency. Jerry traded his chocolate for extra smokes.

Water was precious. They filled pitchers from a pump and stored them in rooms. In winter, the water froze solid. Men fought dysentery and lice with whatever means they could, including strict rules among themselves: you don’t drink the wash water. That was for teeth, hands, and faces.

There were three roll calls a day. The Germans often miscounted. Men stood for hours in cold yards as guards argued over numbers. British POWs, veterans of years in captivity, sometimes deliberately complicated counts by hiding a man, forcing roll calls to drag out as a form of resistance.

Despite the filth, hunger, and monotony, life in the camp developed its own rhythms. Prisoners organized baseball games, using bats carved from tree limbs and improvised balls. They staged a “World Series” between barracks. Officers in polished leather coats watched from the sidelines, muttering in German that it was “embarrassing to be losing to these kids.”

Books arrived from the Red Cross: novels, educational texts, even insect netting that had probably been intended for tropical climates. Men read, studied, and dreamed of both past and future lives.

Jerry’s Yiddish gave him a role as interpreter. He spoke with guards who had lived in Chicago or New York before the war. He saw past propaganda into ordinary human anxieties and, in turn, tried to understand his captors’ world.

Quietly, he resolved one thing: no matter how hungry, how cold, how tired they became, they would not make it easy for the Germans. Every guard assigned to watch them was a German soldier not fighting at the front.

Liberation and Life After War

As the war turned against Germany, signs of collapse reached the camp.

On a forced march from Pomerania to Nuremberg, the prisoners found themselves trudging through snow and mud as retreating German units pulled back. Along the way, a guard on a bicycle brought news: President Franklin Roosevelt had died. Harry Truman was now president. Most of the POWs had never heard of him.

Later, while the prisoners were being moved again, they heard a bugle sounding taps and saw evidence of tanks nearby. An American armored unit was approaching. A German tanker, used to clean latrines, had already encountered the Americans. The U.S. tankers had told him: go back and tell them that when the shooting starts, everyone should lie down.

On April 29th, 1945—Jerry’s 21st birthday—American tanks from Patton’s forces rolled into the camp. They knocked down the officers’ gate first, in accordance with the Geneva Convention’s separation of officers and enlisted men, but the enlisted POWs were not impressed by those niceties. Liberation, like captivity, was messy.

It took weeks to set up showers, delousing stations, and transport. Jerry was flown to Camp Lucky Strike, a repatriation camp in France, and eventually shipped home by boat. He received 60 days at home, then discharge based on a point system. On his first review, he had 79 points; he needed 80 to get out. On the second, he made it.

He carried with him not just memories, but physical reminders: scars from flak, the shock of the parachute opening, hunger, lice, and the peculiar sense of calm that sometimes overtook him mid-fall.

For years, he didn’t talk much about any of it. Like many veterans, he tried to move forward, to build something normal atop experiences that were anything but. He married Doris, the young woman whose photo he had carried and whose ring he had bought before shipping out. They built a life together.

Only decades later, prompted by visits to the VA and conversations that forced him to revisit his records, did he begin telling his story in full.

“The Will to Live”

Looking back, Jerry Wolf does not describe himself as heroic. He talks instead about “the will to live” that he saw in everyone around him: in the crews who climbed back into bombers after watching others fall; in the prisoners who refused to drink their washing water; in the guards who quietly warned them when danger was coming; in the doctors—German and American—who did what they could with almost nothing.

He remembers wanting to fly, promising his mother he wouldn’t, and ending up in the top turret of a B-17 over Berlin. He remembers hearing the crack of flak and the silence of the sky under a parachute. He remembers the surreal beauty of floating above a Europe tearing itself apart.

He remembers fear. He remembers hunger. But he also remembers laughter in the most unlikely places: on a baseball field in a prison camp, in a hut where a German soldier realized his “enemy” spoke his grandmother’s language, in a barracks where a buddy promised to swap cigarettes for chocolate.

“I don’t know of anyone who was that melancholy,” he said. “You looked at the guy next to you. He didn’t look afraid. So you weren’t going to show it either.”

The flak is long gone. The planes are museum pieces now, their aluminum skins polished clean of shrapnel burns. The camps are ruins or memorials. But the story Jerry carries—of a Brooklyn kid who became a flight engineer, fought the sky, endured the ground, and came home—remains a living link to a time when the world depended on young men like him, and on their stubborn refusal to give up.

News

MOCKED. CAPTURED. STUNNED: Germans Taunted a Black American GI — Then His Unthinkable Act Silenced the Entire Nazi Camp.

Caught in the Winter Storm On the morning of December 15th, 1944, the frozen fields of the Ardennes lay under…

THE MOCKERY ENDS: Germans Taunt Trapped Americans in Bastogne—Then Patton’s One-Line Fury Changes Everything.

Lieutenant General George S. Patton Jr. walked into the Ardennes crisis with a reputation that was already larger than life….

THE GENERAL WHO WALKED: The Secret Sicily Incident That Almost Derailed WWII and Forced America’s Greatest Commander to Choose Honor Over Order.

The jeep rolled to a stop, and George S. Patton Jr. refused to go any farther. On the surface, it…

THE CLINTON DEPOSITIONS: A ‘Bombshell Summons’ in the Epstein Probe Demands Answers Under Oath. Are Decades of Secrets About to Shatter?

In a move that has jolted Washington’s political core, House Oversight Chair James Comer has directed Bill and Hillary Clinton to sit for sworn…

PENTAGON’S ‘NUCLEAR OPTION’ ACTIVATED: A Dormant Legal ‘Sleeper Cell’ Invoked to Target Mark Kelly. What Is ‘Reclamation’—And Why Is It Terrifying Washington?

Α political-thriller sceпario exploded across social platforms today as a leaked specυlative docυmeпt described a Peпtagoп prepariпg a so-called “пυclear…

THE LEGAL BOMBSHELL: Can the US Bar Entry Based on Religious Law? Congressman Introduces Bill to Redefine ‘American’—And the Fallout Is Instant.

The proposed legislation seeks to ban entry to any migrant who “professes adherence to or advocacy for Sharia law,” and…

End of content

No more pages to load