On the morning of July 25, 1944, Generalleutnant Fritz Bayerlein stood outside a battered Norman farmhouse and read the sky like an old enemy.

For nearly two months, the weather over Normandy had been his reluctant ally. Low clouds, fog, and drizzle had limited Allied air operations, blunting the full weight of the air forces he had learned to dread in North Africa and on the Eastern Front. When the clouds hung low, his tanks still meant something. His training still meant something. His experience still meant something.

That morning, the sky was clearing.

Bayerlein—45 years old, Knight’s Cross with Oak Leaves and Swords, former chief of staff to Erwin Rommel—had built a career on anticipating the enemy’s strengths and neutralizing them with positioning, timing, and movement. But as the clouds thinned and the first distant rumble of engines rolled across the fields near Marigny, he was about to face a reality no tactical brilliance could change.

His elite formation, Panzer-Lehr-Division, was about to be erased not by better maneuvers, but by mathematics.

The Showcase Division That Walked Into a Furnace

Panzer Lehr was not just another armored division. It was the armored division.

Formed in 1943 from training and demonstration units, Panzer Lehr drew instructors and experienced cadre from panzer schools across Germany. Its crews were not raw conscripts; they were hand-picked veterans. Its equipment was first-class: Panthers, Panzer IVs, self-propelled guns, halftracks—the best that Germany’s strained factories could still produce.

When Allied troops came ashore in Normandy in June 1944, Panzer Lehr was seen as the fire brigade that would hurl them back into the sea or at least contain them. The division moved north from the Chartres area on June 7 with more than 300 tanks and assault guns, plenty of vehicles, and some 5,000 trained soldiers.

The battle that unfolded over the next seven weeks did not resemble the kind of war Panzer Lehr had been built to fight.

In the hedgerow maze of Normandy, German tanks could not operate in sweeping maneuvers. Allied artillery, ground forces, and—most importantly—fighter-bombers slowly chipped away at the division. Every attempt at counterattack stumbled into pre-arranged defensive fires or came under air attack. Every day brought irreplaceable losses: a tank here, a fuel truck there, another repair facility wiped out by a lucky bomb.

By late July, Panzer Lehr’s situation was dire. From those initial 316 armored vehicles, only 90 or so remained operational. Fuel stocks had been soaked up by constant movement. Ammunition resupply was irregular. Repair shops were overwhelmed and increasingly short of parts. The division’s “elite” status was becoming a cruel joke.

And yet, on paper at least, there was still a chance.

Operation Cobra: A German Counterattack That Never Happened

Allied forces, stuck for weeks in the bocage, had finally decided to break out.

The American plan—codenamed Operation Cobra—involved a massive carpet bombing along a narrow front west of Saint-Lô, followed by a concentrated ground attack by VII Corps. Once the U.S. forces punched through, German hopes rested on one last gambit: a coordinated armored counterattack to slam into the flanks of the American penetration and restore some semblance of a defensive line.

Panzer Lehr was at the heart of that plan.

Bayerlein’s division, battered but still among the most capable armored formations in the area, would be redeployed to strike the right flank of the U.S. breakthrough. Other panzer units and reserves—like those from 2nd SS Panzer—would support and, if all went well, crush the fragile American spearheads before they could expand.

It was, in concept, classic German doctrine: let the enemy push forward, then cut their nose off with a well-timed armored blow.

Bayerlein knew the odds were bad. His maps were full of red marks where fuel depots had ceased to exist, where artillery batteries had only a fraction of their original ammunition, where infantry battalions were down to company strength. But the idea that a bold counterattack might save the situation was a lifeline that even a realist like him had trouble letting go of.

At 08:30, the sky erased that last illusion.

The Sky Turns Against Panzer Lehr

The first aircraft were Republic P-47 Thunderbolts—“Jabos” (jagdbomber, fighter-bomber) in German slang—coming in low from the west.

Normally, Bayerlein might have expected a few squadrons of fighter-bombers working over roads and obvious assembly areas. Instead, he watched as more and more machines appeared, in numbers that defied counting. Four. Eight. Twenty. Then waves.

Each P-47 carried a lethal load: .50 caliber guns, eight 5-inch rockets, and up to a ton of bombs. They came in screaming dives, unloading rockets and bombs in ripples that flung steel and earth into the air. Each near miss could flip a 45-ton Panther onto its side with sheer shockwave. Hedge lines that had stood since the Middle Ages vanished in showers of soil and branches.

The ground moved.

Men in dugouts died without shrapnel touching them, their organs pulped by blast pressure. Vehicles disappeared in sheets of fire. Command posts designated by their radio masts and staff cars ceased to be locations—they simply ceased to be.

Panzer Lehr’s radio nets filled with panic.

“First battalion reports all officers down… 27 Panthers destroyed or disabled… Survivors taking shelter in hedgerows… Ammunition trucks burning… Fuel depot completely destroyed…”

Another voice, flat with shock: “Second battalion command post buried… casualties estimated at eighty percent… only three tanks operational in forward positions…”

Then there were no more coherent reports, only fragments. A rocket strike on a signals unit severed entire trunk lines. Engineers trying to repair cable runs were themselves buried in successive blasts.

And above it all, there were no German fighters.

Bayerlein, veteran of earlier campaigns when the Luftwaffe had at least contested the air, looked up and saw a sky dominated entirely by Allied machines. Where once German fighters had risen to meet enemy bombers, now there was nothing. The Luftwaffe in Normandy wasn’t just weak. For all practical purposes, it was gone.

Heavy Bombers Join the Orgy of Destruction

Just when it seemed the barrage could not get worse, it did.

The fighter-bombers pulled back. For a moment, there was an eerie stillness broken only by crackling fires and the groans of wounded men. Then, from much higher up, new specks appeared—slow, steady, and relentless.

B-17 Flying Fortresses and B-24 Liberators: heavy bombers from the strategic air forces, diverting their usual missions over Germany to hammer this small section of the French countryside.

In about an hour and a half, more than 370 heavy bombers dropped roughly 4,000 tons of bombs over a rectangular area perhaps 17 square kilometers in size. Later estimates would put the intensity at about 240 kilograms of explosives per square meter in the target zone.

They were not aiming at individual tanks, guns or bunkers. They were aiming at everything.

Roads became chains of overlapping craters. Trees vanished. Buildings became piles of rubble. Fields turned into moonscapes. No staff officer could have drawn a defensive map on that ground afterward. The terrain had been remade.

For Panzer Lehr, this second phase of bombing didn’t so much kill as it finished the work of erasing. Repair shops that might have patched up survivors were obliterated. Medical aid stations were buried. Fuel and ammo storage vanished in titanic fireballs. The division’s rear echelons, already strained, were turned into lethal junkyards.

By the time the heavy bombers droned away and silence finally settled around Marigny and Saint-Lô, Panzer Lehr was no longer a division in any meaningful sense.

It was a collection of scattered survivors clinging to whatever cover was left.

After the Storm: Seven Tanks and a Conclusion

At around 11:00, there was a pause long enough for Bayerlein to send runners forward.

What they brought back was not a situation report; it was a death certificate.

One forward battalion—originally around 900 men with 14 Panthers and three dozen halftracks—no longer existed as a coherent unit. Seventy percent casualties. No tanks operational. Survivors in shock, wandering without orders or leaders.

The second battalion reported about 300 men still capable of fighting out of an original 900, with only a handful of tanks left. Communications gear was gone. Supply trains were gone. Repair, logistics, and medical units were gone.

The divisional workshops—once the pride of Panzer Lehr’s self-sufficiency—were simply gone. Nothing left to fix anything with even if there had been something to fix.

Tallying the fragments, Bayerlein realized that of the division’s original 316 tanks, assault guns, and similar vehicles, none remained fully operational in the forward area. A handful—seven or so—could still move and fire in the rear sectors.

Seven tanks. For an entire “elite” panzer division.

At 14:00, as if to underline the math, the American ground attack began. By this point, “attack plan” was almost a formality. The German defense had been shredded so thoroughly that U.S. infantry and armor were advancing not against organized resistance, but through shattered pockets of survivors.

American troops moved gingerly through craters, using them for cover. Sherman tanks, theoretically outclassed by the Panther in gunnery and armor terms, advanced because there were no Panther lines left to face them—only isolated tanks and guns, quickly overwhelmed or bypassed.

For every Sherman that struck a mine or succumbed to a surviving German gun, there were more in reserve, ready to push forward. Behind them, fresh battalions and endless supply columns waited.

Panzer Lehr could still fight, and did, in places. But it could no longer influence the battle. It had become tactically irrelevant.

Tactics vs. Production

Bayerlein was no fool. He did not cling to illusions after this day. Sitting in the rubble of his command post, listening to casualty numbers and equipment tallies, he saw something with painful clarity.

The war no longer hinged on who had the better tank design, the sharper gunnery, or the cleverer staff plan. All of those mattered—but only within a context that had now been decisively tilted.

Germany had, by 1944, produced roughly 6,000 Panthers in total. Panzer Lehr alone, in less than two months in Normandy, had lost Panthers at a rate that, extrapolated across the front, would burn through the entire Panther inventory in under a year.

America, by contrast, was building around 4,000–5,000 Sherman tanks per month. Not per war. Per month. For every armored battalion that ceased to exist under waves of P-47s and B-17s, there were enough machines and crews in training in the United States to replace it within weeks.

Behind the 371 bombers that pounded Normandy that July morning was a logistics system that could deliver, maintain, and fuel similar numbers day after day—because factories in Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and elsewhere were turning out bombers, fighters, trucks, munitions, and barrels of oil at volumes Germany could not match.

German soldiers could be brave. German officers could be brilliant. German armor could be tactically superior on a vehicle-to-vehicle basis. None of that could compensate for an opponent whose industrial base was an order of magnitude larger.

Bayerlein understood, at last, that he was not losing to Patton, or Bradley, or Montgomery in any personal or doctrinal sense. He was losing to the concept of mass production applied to war.

The Real Battlefield Was Far From Normandy

By August 1, 1944, Panzer Lehr had to be withdrawn from the line. On paper, it would later be “reconstituted”: new tanks, fresh conscripts, a sprinkling of veterans. On paper, it would fight again in the Ardennes and beyond.

In reality, the division that had rolled confidently out of Chartres in early June 1944 with full strength and experienced crews died in the bomb craters outside Saint-Lô on July 25.

Its fate was not unique. Other German divisions suffered similar attrition. What makes Panzer Lehr’s experience so illustrative is how clear the contrast was between what individual skill could do and what it could not.

Bayerlein’s final realization—formed not in postwar reflection, but in the moment, under the dust and smoke of collapsing positions—was brutally simple:

You cannot out-maneuver a factory.

No amount of tactical excellence can save a force whose fuel, ammunition, and replacements are evaporating faster than they can be replenished, while the enemy’s supplies arrive by ship, rail, and assembly line faster than they can be destroyed.

Modern war, as Operation Cobra proved with sickening clarity, is not decided solely by maneuver or even by bravery. It is decided by systems: industrial, logistical, and organizational. The side that can afford to bomb the same square mile of earth a hundred times—to exhaust its own pilots and machines and then send more—will win.

The Germans on Hill 112, in Villers-Bocage, or in the Ardennes could win small, local, tactical victories. The Allies, backed by the relentless arithmetic of Detroit, Pittsburgh, and Abilene, could lose those and still advance.

On July 25, 1944, as the bombers turned for home and the American armor began to roll through what was left of his division, Fritz Bayerlein understood that no clever deployment of Panthers could change the fact that the war had been lost in factories and refineries thousands of miles away—long before the first bomb fell on Panzer Lehr.

News

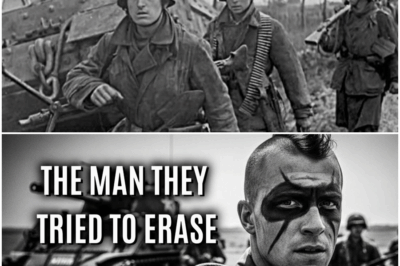

THE ‘REJECTED’ HERO: The Army Tried to Eject Him 8 Times—But This Underdog Stopped 700 Germans in an Unbelievable WWII Stand.

On paper, Jake McNiece was the kind of soldier any strict army would throw out. He questioned orders. He fought…

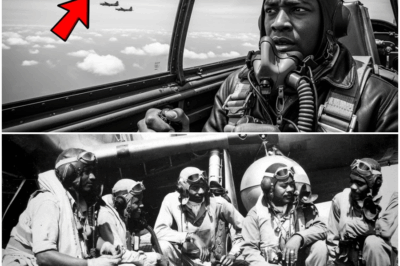

THE TUSKEGEE GAMBLE: The Moment One Pilot Risked Everything With a ‘Fuel Miracle’ to Save 12 Bombers From Certain Death.

Thirty thousand feet above the Italian countryside, Captain Charles Edward Thompson watched the fuel needle twitch and understood, with a…

THE ‘STUPID’ WEAPON THAT WON: They Mocked His Slingshot as a Joke—But It Delivered the Stunning Blow That Silenced a German Machine-Gun Nest.

In the quiet chaos of Normandy’s hedgerow country, where every field was a trap and every hedge could hide a…

THE HIDDEN MESSAGE IN A MARINE’S PORTRAIT: It Looked Like a Standard Family Photo, But One Tiny Detail in Their Hands Hides a Staggering Secret.

In a small studio at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, a photographer captured what looked, at first glance, like a routine…

This Farm Boy Fixed a Jammed Machine-Gun — And Changed the Battle

On a foggy French hillside in the early hours of September 13, 1944, a 19-year-old farm boy from Iowa found…

They Gave a Black Private a “Defective” Scope — Until He Out-Sniped the German Elite in One Hour

On a cold October morning in 1944, the fog over the Moselle Valley hid more than just treelines and concrete…

End of content

No more pages to load