The Race for Messina: How the Fiercest Rivalry of World War II Re-shaped the Allied War Effort

August 17, 1943.

Two clouds of dust rose on the twisting roads leading toward Messina, Sicily—one marked by the Union Jack, the other by the Stars and Stripes. Two armies were racing, not for a defensive line, not for a strategic crossroads, but for a symbolic triumph that had consumed their commanders for weeks.

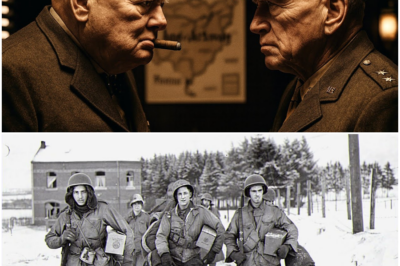

In one column rode Lieutenant General George S. Patton, pushing his exhausted troops forward with relentless urgency. In another rode General Bernard Law Montgomery, equally determined to arrive first.

Messina was the final prize of the Sicilian campaign, the gateway to mainland Italy, and the trophy that would define the reputations of both men. Whoever seized the port city first would claim the victory. Whoever arrived second would carry the humiliation for the rest of the war.

Montgomery knew this. Patton knew this. And from the moment their boots hit Sicilian soil, the rivalry that would become the most famous feud of the Allied war effort ignited.

The Making of Montgomery: Britain’s Symbol of Revival

To understand why the rivalry mattered so much, one must first understand who Bernard Montgomery was in the summer of 1943.

He wasn’t simply a commander; he was a national symbol.

For three years, Britain’s armies had suffered shattering defeats—Dunkirk, Greece, Crete, Singapore, Tobruk. The British public had endured setbacks across continents, and confidence in the army had faded.

Then came El Alamein.

In October 1942, Montgomery delivered Britain’s first major land victory of the war, defeating Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Korps and reversing the momentum in North Africa. Winston Churchill called it “the end of the beginning.” Newspapers praised Montgomery’s leadership. Soldiers admired his discipline, his meticulous planning, his personal messages to the troops.

A distinctive black beret, two cap badges, and an unmistakable air of certainty made him instantly recognizable.

Montgomery believed he was the finest general alive—and Britain agreed.

Patton: Brilliant, Unproven, and Furious

Across the Atlantic, George Patton faced a different reality. He had the talent, the aggression, and the audacity of a battlefield virtuoso—but lacked the reputation.

The Americans had suffered a humiliating defeat at Kasserine Pass in February 1943. Patton was sent to fix the disaster. He imposed harsh discipline, rebuilt morale, and reshaped the Second Corps into a fighting force that soon proved itself against German armor.

But in the public eye, Montgomery received the glory.

Patton, who had salvaged the American front, felt overshadowed. British newspapers emphasized Montgomery’s triumphs, not America’s recovery. As the Allies prepared to invade Sicily, Patton saw an opportunity—not just for strategic victory, but for personal vindication.

And Montgomery saw an opportunity to protect the legacy he’d worked so hard to construct.

The Plan for Sicily—And the First Clash

Operation Husky, the Allied invasion of Sicily, was supposed to be a joint triumph. The original plan gave both armies major roles: Patton’s U.S. Seventh Army would seize the western half of the island while Montgomery’s Eighth Army advanced up the eastern coast toward Messina.

But Montgomery rejected this balanced approach.

He insisted that the Eighth Army should make the main drive toward Messina, relegating Patton to a defensive flank-guarding role. He appealed directly to Eisenhower. With coalition unity hanging by a thread, Eisenhower agreed.

For Patton, it was a professional insult.

For Montgomery, it was confirmation of his primacy.

But reality did not cooperate.

Montgomery Stalls, Patton Moves

Montgomery’s forces made a successful landing on Sicily’s southeastern beaches—but soon encountered entrenched German defenses around Catania. The coastal highway he planned to use for a rapid advance became a grinding battlefield of attrition. Progress stalled for days. Then weeks.

Montgomery blamed the terrain.

He blamed German resistance.

He blamed American forces for not drawing off enough enemy troops.

He did not blame his plan.

Meanwhile, Patton sat on the western flank with far more troops than necessary for the mission he’d been assigned. Watching Montgomery struggle, he saw a chance to reshape the campaign.

He proposed to General Harold Alexander that instead of waiting, he would strike westward across the island and seize Palermo. Alexander—a British officer who understood the need for flexibility—agreed.

Patton unleashed his army.

In seventy-two hours, the U.S. Seventh Army swept across mountains, captured Palermo, secured thousands of prisoners, and seized an enormous stockpile of supplies.

The headlines shifted overnight.

The world now knew the name George S. Patton.

Montgomery did not appreciate the competition.

The Race to Messina

With Palermo secured, Patton pivoted east. Montgomery, still battling German defenses, now found himself in a real—and deeply personal—race.

Messina was the objective of both armies now, whether Allied headquarters intended it or not. Montgomery launched flanking attacks and even attempted amphibious landings behind German positions. But progress remained slow.

Patton advanced aggressively along Sicily’s northern coast, using leapfrog amphibious operations to bypass German roadblocks and keep momentum alive.

Both armies pushed beyond reasonable limits.

Both commanders accepted risks they might otherwise have avoided.

The rivalry had taken on a momentum of its own.

Patton won.

At dawn on August 17, 1943, American forces entered Messina. Montgomery’s troops arrived hours later to find American flags already flying. Patton arranged a theatrical greeting for the British officers who arrived—gracious on the surface, unmistakably triumphant beneath it.

Montgomery did not attend. He sent subordinates rather than face the moment in person.

The message was unmistakable:

The United States Army was no longer a junior partner.

Victory—and a Hidden Cost

Patton considered Messina one of the greatest triumphs of his career. Yet as the celebrations faded, trouble appeared on the horizon.

During the Sicilian campaign, Patton had committed two grave errors: he slapped two soldiers suffering battle fatigue, accusing them of lacking courage. The incidents leaked to the press. Public outrage followed. Eisenhower ordered Patton to apologize to the units involved. Politicians demanded his dismissal.

Eisenhower refused to lose a commander as gifted as Patton—but he now had a reason to sideline him during the next phase of planning.

Montgomery quietly encouraged the idea that Patton was unreliable and lacked discipline suitable for high command.

When preparations began for the invasion of France, Montgomery was named ground commander.

Patton was assigned to lead a fictitious army designed to deceive the enemy.

Normandy: The Rift Widens

On June 6, 1944, Montgomery directed the land battle on D-Day. It was the pinnacle of his authority. But as operations progressed, his performance drew criticism.

He promised to seize Caen on the first day.

It took more than a month.

Repeated British offensives stalled against German defenses.

American forces ultimately achieved the breakout at Saint-Lô.

Then came August 1, 1944.

Patton’s Third Army became operational.

What followed was one of the most dynamic campaigns in military history. Patton advanced across France with astonishing speed—20, 30, even 50 miles per day. Towns fell so quickly that German headquarters often did not learn of their loss until hours later.

The comparison became impossible to ignore.

Montgomery was still battling hedgerows.

Patton was racing toward Germany.

Montgomery watched the transformation of his rival—from controversial subordinate to headline hero—with profound resentment.

Market Garden: A Risk That Broke the Alliance’s Patience

As the Allies neared Germany, Montgomery proposed a bold idea: concentrate all available forces into a single thrust under his command. The goal was to end the war by Christmas.

Patton argued the opposite—that the Allies should advance broadly and exploit German weaknesses across multiple fronts.

Eisenhower compromised. Montgomery received priority for a special operation—Market Garden—while Patton’s army suffered fuel shortages.

Market Garden, launched in September 1944, was one of the most daring operations of the war. It was also one of the most costly failures. German defenses proved stronger than expected, and the crucial bridge at Arnhem could not be held.

Patton’s warnings proved prescient.

Montgomery’s prestige was shaken.

The rivalry deepened.

The Battle of the Bulge and Montgomery’s Misstep

In December 1944, German forces launched a surprise offensive through the Ardennes forest. The Battle of the Bulge began. Eisenhower placed Montgomery in temporary command of the northern sector while Patton executed an extraordinary maneuver—pivoting three divisions 90 degrees in winter conditions to relieve Bastogne in just 48 hours.

It was one of the most remarkable military responses of the war.

But after the crisis, Montgomery held a press conference that nearly ruptured the Allied coalition. He implied that his leadership had stabilized the front, while American forces had faltered. He barely acknowledged Patton, Bradley, or the extraordinary defense of Bastogne.

American newspapers reacted angrily. Allied unity wavered. Eisenhower intervened directly to calm the situation.

Montgomery’s remarks had reopened every wound of the Patton-Montgomery feud.

Final Acts and Final Verdicts

In March 1945, the U.S. Ninth Armored Division captured the Ludendorff Bridge at Remagen—giving the Allies their first crossing over the Rhine. Days later, Patton crossed on an improvised assault, further undercutting Montgomery’s long-planned river crossing operation.

The war ended weeks later.

Patton died in December 1945 before writing memoirs that might have answered Montgomery’s later accusations. Montgomery lived until 1976, shaping his own legacy in books and interviews.

Yet history has rendered its judgment.

Montgomery is remembered as a structured, methodical, sometimes rigid commander—capable but cautious, celebrated at times beyond the scale of his achievements.

Patton is remembered as one of the most dynamic field generals in American history—flawed, volatile, but brilliant in operational command.

The rivalry between them shaped campaigns, influenced strategy, and absorbed countless hours of Eisenhower’s energy. It was a partnership that succeeded despite itself—and a rivalry that became one of the defining dramas of the Allied war effort.

In the end, the general who died young became a legend.

And the one who lived long enough to tell the story was forced to share the stage with the rival he could never outrun.

News

THE THRILL OF IT’: What Churchill Privately Declared When Patton Risked the Entire Allied Advance for One Daring Gambit

The Summer Eisenhower Saw the Future: How a Quiet Inspection in 1942 Rewired the Allied War Machine When Dwight D….

‘A BRIDGE TO ANNIHILATION’: The Untold, Secret Assessment Eisenhower Made of Britain’s War Machine in 1942

The Summer Eisenhower Saw the Future: How a Quiet Inspection in 1942 Rewired the Allied War Machine When Dwight D….

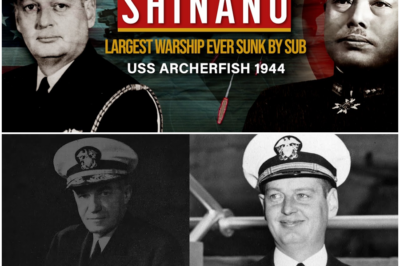

THE LONE WOLF STRIKE: How the U.S.S. Archerfish Sunk Japan’s Supercarrier Shinano in WWII’s Most Impossible Naval Duel

The Supercarrier That Never Fought: How the Shinano Became the Largest Warship Ever Sunk by a Submarine She was built…

THE BANKRUPT BLITZ: How Hitler Built the World’s Most Feared Army While Germany’s Treasury Was Secretly Empty

How a Bankrupt Nation Built a War Machine: The Economic Illusion Behind Hitler’s Rise and Collapse When Adolf Hitler became…

STALLED: The Fuel Crisis That Broke Patton’s Blitz—Until Black ‘Red Ball’ Drivers Forced the Entire Army Back to War

The Silent Army Behind Victory: How the Red Ball Express Saved the Allied Advance in 1944 In the final week…

STALLED: The Fuel Crisis That Broke Patton’s Blitz—Until Black ‘Red Ball’ Drivers Forced the Entire Army Back to War

The Forgotten Army That Saved Victory: Inside the Red Ball Express, the Lifeline That Fueled the Allied Breakthrough in 1944…

End of content

No more pages to load