THE PILOT WHO REFUSED TO LET HIS CREW DIE:

The Extraordinary Story of 1st Lt. William Lawley and Cabin in the Sky, February 20, 1944**

On February 20th, 1944, at exactly 11:37 a.m., a brand-new B-17 Flying Fortress clawed its way through 12,000 feet of cold air above the English Channel. Inside the cockpit sat a 23-year-old pilot, First Lieutenant William Lawley, staring at the unblemished instrument panel of an aircraft that had never tasted combat until that moment.

The crew had named her Cabin in the Sky.

Before the day was over, she would become one of the most battered aircraft ever to limp back to England—on fire, spiraling, nearly uncontrollable, and kept aloft by a pilot who flew with only one functioning arm and a fading grip on consciousness.

This was the opening day of Big Week—Operation Argument—the largest coordinated bomber offensive the United States had yet undertaken. Over 1,000 American heavy bombers were pushing deep into Germany, striking aircraft factories and industrial targets with a single strategic purpose:

Destroy the Luftwaffe before the invasion of Europe.

Without air superiority, D-Day would fail before the first soldier touched sand.

The Mission Begins

Cabin in the Sky was only ten days removed from the Douglas assembly line in California. Her aluminum skin was spotless; her rivets gleamed; her engines hummed with perfect factory-tuned rhythm.

She was also flying into one of the most dangerous regions on Earth.

The Luftwaffe had scrambled roughly 20 Bf 109 interceptors. Radar stations tracked the long bomber stream threading toward Leipzig, home to several critical aircraft production facilities. Germany knew the stakes. If these factories fell, their fighter strength would collapse.

Lawley’s crew was one of thousands who understood that the survival of the invasion depended on this day.

Inside the B-17 were:

Pilot: 1st Lt. William Lawley

Co-Pilot: 2nd Lt. Paul Murphy

Navigator: Lt. Harry Saraphine

Bombardier: Lt. Harry Mason

Radio Operator: Sgt. Thomas Dempsey

Ball Turret Gunner: T/Sgt. Joseph Koburetsky

Top Turret Gunner: Sgt. Carol Rowley

Waist Gunners: Sgt. Ralph Brazwell and another crewmember

Tail Gunner: Sgt. Alfred Went

Ten men.

Four engines.

Nine previous missions behind them.

And ahead—Leipzig, one of the deepest and most heavily defended targets yet attempted.

Into Leipzig

The city ahead still smoldered from an RAF night raid. Smoke drifted upward in gray sheets. German anti-aircraft batteries—well-practiced, well-prepared—waited for the incoming American wave.

At 14:24, flak began.

Black bursts hammered the formation. The B-17 shuddered as fragments peppered the fuselage. Lawley kept her level; Mason in the nose called out the aiming points; the formation held true.

At 14:28, Cabin in the Sky released her bombs—four tons of explosives plunging toward the Messerschmitt factory complex.

But it was the turn off target that the Germans anticipated most.

The Luftwaffe struck at 14:31.

The Head-On Attack

Major Walter Brede and nearly twenty Bf 109s came screaming out of the sun in a perfect head-on dive—a tactic designed to kill the pilots and shatter the bomber’s command structure. At a closing speed approaching 500 mph, the Germans fired their 20 mm cannons.

Cabin in the Sky’s gunners fired back, but the fighters passed through the formation too quickly for prolonged bursts.

One Bf 109 lined up directly on Lawley’s aircraft.

The first 20 mm shell punched through the cockpit, exploding between the pilot and co-pilot seats.

Shrapnel tore into Lawley’s face and right arm.

Murphy, the co-pilot, was killed instantly.

The second shell destroyed the instrument panel.

The third hit engine number two, igniting an orange fireball.

Five more shells slashed through the fuselage, hitting nearly every gun position.

Eight of the ten men aboard were wounded.

Cabin in the Sky fell into a steep, uncontrolled dive.

One Hand on the Controls

Murphy’s lifeless body had collapsed onto the control column, forcing the bomber downward. Lawley, blinded by blood and unable to use his right arm, grabbed the column with his left hand—but he couldn’t overpower the weight alone.

He hooked his boot against the panel, braced his body, and pulled Murphy’s body off the controls. The effort tore new wounds open across his arm and chest. With his last strength, he hauled the aircraft level again at 11,000 feet, barely above structural failure speed.

But they were now alone.

Five miles behind the formation.

On fire.

With three engines barely functioning.

And German fighters circling for another attack.

The Decision No Pilot Wants to Make

At 14:41, Lawley made the call:

Prepare to bail out.

The situation was hopeless. The burning engine could detonate the wing tanks at any moment. The tail controls were partially severed. The hydraulics were gone. The electrical system was failing. Ammunition was nearly depleted.

But when the waist gunners checked the wounded, they found the truth:

Two crewmen could not jump.

Radio operator Sgt. Dempsey’s legs were shredded.

Ball turret gunner T/Sgt. Koburetsky couldn’t move from neck injury and shrapnel.

If the others bailed out, those two men would certainly die when the aircraft crashed.

Lawley looked at the burning engine. His shattered controls. His useless right arm. Then he made the most courageous decision of his life.

He said:

“We are staying with the ship.”

And one by one, every man aboard chose to stay with him.

The Longest Flight Home

The next 90 minutes were a battle of physics, pain, and pure will.

The Aircraft Was Dying

Engine #2 burned uncontrollably.

Engine #4 leaked oil and threatened to seize.

The fuel transfer system malfunctioned.

Hydraulics were gone—no flaps, no brakes, no landing gear assist.

Electrical power flickered out.

Cabin heat and oxygen were compromised.

Lawley’s right arm hung limp.

His vision narrowed into a tunnel from blood loss.

The Crew Worked as One

Mason became an impromptu co-pilot, operating throttles and switches.

Saraphine navigated through dead reckoning.

Gunners, though wounded, fended off two more fighter passes.

The waist gunners threw out equipment to lighten the load.

Men bandaged each other as best they could in the freezing cabin.

Lawley Fought Consciousness

Twice he passed out from shock.

Twice his crew revived him just in time.

When the aircraft hit cloud banks at 7,000 feet, Lawley—half-blind and fading—flew by instruments alone. When engine #4 began to die, he coaxed it back to life. When #3 caught fire, he kept the airplane steady despite the wing glowing from heat.

Finally, at 16:23, they crossed the Dutch coast.

At 17:03, the English shoreline appeared.

The last engine sputtered on fumes.

The Landing That Should Have Been Impossible

Lawley spotted a small grass airfield—RAF Redhill—and aimed for it. With no flaps and only one engine, the approach was uncontrollable. Mason hand-cranked the landing gear—200 turns—and hoped it locked.

At 70 mph, barely above stall speed, Cabin in the Sky touched down on soft earth. The aircraft bounced, skidded, and tore into the grass.

But she stayed upright.

At 17:08, the burned-out B-17 rolled to a stop.

Ten men climbed out.

Eight wounded.

One gone.

None left behind.

Cabin in the Sky had completed her first—and last—mission.

Aftermath and Honor

Fire crews extinguished the burning wing. Wounded crewmen were rushed to hospitals. Lawley, barely conscious, watched from the grass as the sun set over England.

Months later, Congress recognized the magnitude of what he had done.

For saving nine lives, flying a crippled aircraft through enemy territory, refusing to abandon his wounded, and landing a bomber with only one functioning arm, 1st Lt. William Lawley Jr. received:

The Medal of Honor

His citation reads, in part:

“Displaying conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty…”

Lawley survived the war, returned home, and lived a long life—quiet, modest, never forgetting the men he refused to leave behind.

Cabin in the Sky did not fly again.

But her final landing remains one of the most remarkable acts of airmanship in aviation history.

News

GHOSTS IN THE SKY: The Devastating Mission Where Only One B-17 Flew Home From the Skies Over Germany

THE LAST FORTRESS: How One B-17 Returned Alone from Münster and Became a Legend of the “Bloody Hundredth”** On the…

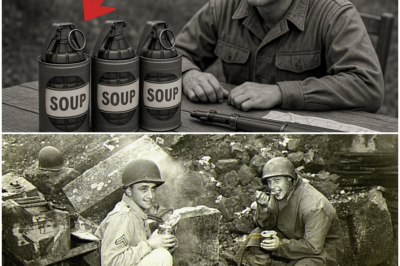

THE SOUP CAN CARNAGE: The Incredible, True Story of the U.S. Soldier Who Used Improvised Grenades to Kill 180 Troops in 72 Hours

THE SILENT WEAPON: How Three Days, One Soldier, and a Handful of Soup Cans Stopped an Entire Advance** War rarely…

UNMASKED: The Identity of the German Kamikaze Pilot Whose Final Tear Exposed the True Horror of Hitler’s Last Stand

THE LAST DIVE: The Sonderkommando Elbe, a Falling B-17, and a Miracle Landing On April 7th, 1945—just weeks before the…

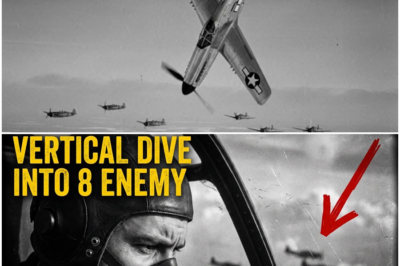

THE MUSTANG’S MADNESS: The P-51 Pilot Who Ignored the Mockery to Break Through 8 FW-190s Alone in a ‘Knight’s Charge’ Dive

THE DIVE: How One P-51 Pilot Rewrote Air Combat Over Germany The winter sky over Germany in late 1944 was…

JUDGMENT DAY SHOCKWAVE: Pam Bondi Unleashes Declassified Evidence for Probe Targeting Architects of Anti-Trump Attacks

A wave of social-media posts is circulating a dramatic claim:“Pam Bondi has officially launched the investigation Hillary Clinton prayed would…

VETERAN’S HORROR: Ex-Army Soldier Recounts Shocking ICE Abuse, Claims Agents Smashed Window and Knelt on His Neck

A Veteran’s Testimony: Inside the Alarming Case That Sent Shockwaves Through Congress When George Retes took his seat before the…

End of content

No more pages to load