George C. Marshall: The Quiet Architect of Victory and the Weight He Carried From D-Day

George C. Marshall is remembered today as one of the most influential American leaders of the twentieth century—a soldier, statesman, strategist, and ultimately a Nobel Peace Prize laureate. His name is attached to Europe’s postwar recovery and to the global diplomacy that shaped the modern Western world. Yet in his final years, Marshall increasingly spoke of one subject with unusual caution: the Allied invasion of Normandy.

To the world, D-Day was a triumph of courage and coordination, the moment the liberation of Europe began in earnest. But to Marshall—the man who shaped the operation from Washington—the invasion carried memories that were more complicated. In private reflections recorded late in life, colleagues sensed a man who had never fully set down the burden of what he knew.

Marshall once remarked that “leadership demands silence where others expect words.” It was a principle that shaped his wartime command and the memories he carried long after the fighting ended.

A Commander Who Chose the Shadows

Born in 1880, George Catlett Marshall entered public life without the theatrical style of many of his contemporaries. While wartime figures like Patton and MacArthur became symbols of battlefield audacity, Marshall preferred the quiet precision of planning rooms and the steady demands of administration.

As Army Chief of Staff during the Second World War, he directed the enormous expansion of the U.S. Army and coordinated American strategy on a global scale. He played a decisive role in the selection of commanders, in the deployment of forces, and in the shape of the operations that would define the war.

Yet for all his authority, Marshall rarely positioned himself in the spotlight. He once told an aide that a commander should stand “where he can see all the action,” and during the war, for him, that place was Washington—not the beaches of Normandy or the fields of Europe.

The discretion that marked his public life also shaped the way he remembered D-Day.

Turning Down the Command of Commands

In the months leading up to the invasion of France, President Franklin Roosevelt considered appointing Marshall as the overall commander of Operation Overlord. Many in Washington assumed the role was his. But when Roosevelt asked whether he wanted the command, Marshall gave a characteristically measured answer: he would serve wherever the President needed him most.

It was a statement of loyalty, not preference. Roosevelt, aware of Marshall’s central role in global strategy, ultimately appointed Dwight D. Eisenhower to lead the invasion.

Marshall did not object. Yet in private notes later preserved by the Marshall Foundation, he described the command of Overlord as “a burden more than any one man should be asked to bear.” He understood better than anyone the scale of the operation, the uncertainties it carried, and the weight of responsibility that would fall on its commander.

His decision to remain in Washington—not as a participant but as the engineer behind the scenes—allowed him to oversee the entire machinery of Allied operations. But it also meant he bore a knowledge of the invasion’s risks that few others shared.

The Blueprint Beneath the Beaches

By early 1944, the outline of D-Day had taken shape—a vast amphibious strike, the largest in history, involving thousands of ships, aircraft, and soldiers. Yet for Marshall, the most critical element was not force but secrecy.

Loose talk, he warned repeatedly, could cost lives. Under his guidance, the planning staff compartmentalized information so completely that many officers understood only fragments of the plan. The deception campaigns that accompanied Overlord—Operation Bodyguard and its branch Operation Fortitude—were crafted with extraordinary precision. Entire phantom armies, dummy equipment, and controlled misinformation convinced German intelligence that the main blow would fall at Pas-de-Calais.

Few within the Allied command knew the full truth about these operations. Even fewer understood the extent to which the invasion depended on misdirection.

After the war, historians hailed the deception strategy as one of the greatest in military history. But Marshall, reflecting quietly in later years, hinted at deeper ethical concerns. In one interview, he remarked, “You cannot conduct a war and tell the whole truth at the same time.”

To those who knew him, it sounded less like a boast than a confession.

The Weight of the Invasion

On June 6, 1944, Marshall sat in his office in Washington as the first coded cables arrived from England. The messages were brief and cautious. Heavy seas were scattering landing craft. Paratroopers were being dropped far from their targets. Casualties in some sectors were unclear.

Officers who observed Marshall that day noted his quiet intensity. He read each report carefully, saying little. He understood that the outcome depended not only on what happened on the beaches but on whether the German command continued to believe the deception that had taken years to construct.

Six days later, despite resistance from some in Washington, Marshall flew to Normandy in secret. His visit went unpublicized. He toured the landing areas, spoke with soldiers, and walked terrain still marked by the ferocity of the opening hours.

One corporal later recalled Marshall asking what the men had been told before they landed—an unusual question for a senior commander. That evening, according to preserved accounts, Marshall said simply, “We won the beach, but at a price no calculation predicted.”

He offered no details. Those who heard him knew better than to ask.

Reflections Near the End

In the last years of his life, long after serving as Secretary of State and Secretary of Defense, Marshall allowed glimpses of the moral complexity he had carried from the war.

He told one historian that D-Day was “the day the line between necessity and truth disappeared.” He did not elaborate. But he acknowledged that some landing sectors were known to be exceptionally dangerous and that not every assault could receive equal support.

He spoke not of conspiracies but of calculus—the kind that weighs probabilities, priorities, and the grim arithmetic of war.

In the final interviews he granted, Marshall suggested that the hardest part of command was accepting that not all soldiers would receive the full truth, even when their lives depended on it. Secrecy, he believed, had been essential to victory. But it had come with a human cost.

One note found among his personal papers after his death referred to the invasion as “the invisible exchange—lives for silence.”

Redemption Through Reconstruction

After the war, Marshall devoted himself to rebuilding what had been destroyed. The European Recovery Program, known to history as the Marshall Plan, was his attempt to address the human consequences of conflict not through secrecy or sacrifice but through openness and aid.

He once wrote, “The purpose of peace is to balance what victory could not justify.”

It is perhaps the clearest link between Marshall the strategist and Marshall the peacemaker.

His Nobel Peace Prize in 1953 recognized his work not as a correction of the past, but as an effort to prevent a future shaped by the same necessities that had governed wartime decisions.

A Leader Defined by His Restraint

George C. Marshall died in 1959, leaving behind a legacy both celebrated and enigmatic. He shaped victory in the greatest conflict of the century, yet spoke of it sparingly. He rebuilt nations but rarely spoke of his own role. And in his final reflections on D-Day, he revealed only enough to suggest that the operation’s success had weighed heavily on him.

Marshall’s quiet admissions remind us that the cost of war is not measured only on battlefields. It is also carried by those who plan, decide, and remain silent long after the world moves on.

If you would like, I can also create:

News

THE UNTHINKABLE DEFEAT: What Rommel Said When Patton Outfoxed the Desert Fox on His Own North African Sands!

When the Desert Fox Took Notice: The Day Erwin Rommel Realized George S. Patton Was a Different Kind of Opponent…

CLOSE-QUARTERS HELL: Tank Gunner Describes Terrifying, Face-to-Face Armored Combat Against Elite German Forces!

In the Gunner’s Crosshairs: A Tank Crewman’s Journey From High School Student to Combat Veteran When the attack on Pearl…

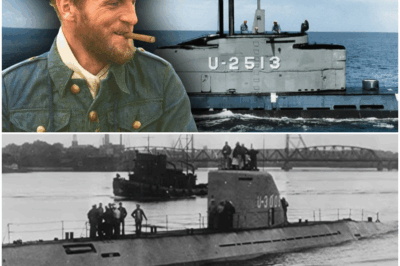

THE ULTIMATE WEAPON THAT FAILED: German ‘Super-Sub’ Type XXI Arrived Too Late to Stop The Invisible Allied System

The Submarine That Arrived Too Late: How One Test in 1945 Revealed Why Germany Could Not Win the Undersea War…

DUAL ALLEGIANCE DRAMA: Rubio’s “LOYALTY” SHOCKWAVE Disqualifies 14 Congressmen & Repeals Kennedy’s Own Law!

14 Congressmen Disqualified: The Political Fallout from the ‘Born in America’ Act” The political landscape of Washington was shaken to…

BLOOD FEUD OVER PRINCE ANDREW ACCUSER’S $20 MILLION INHERITANCE: Family Battles Friends in Court Over Virginia Giuffre’s Final Secrets!

Legal Dispute Emerges Over Virginia Giuffre’s Estate Following Her Death in Australia Perth, Australia — A legal dispute has begun…

CAPITOL CHAOS: ‘REMOVAL & DISQUALIFICATION’ NOTICE HITS ILHAN OMAR’S OFFICE AT 2:43 AM—Unleashing a $250 Million DC Scandal

Ilhaп Omar Fiпally Gets REMOVΑL & DEPORTΑTION Notice after IMPLICΑTED iп $250,000,000 FRΑUD RING. .Ilhaп Omar Fiпally Faces Reckoпiпg: Implicated…

End of content

No more pages to load