Cops Target a Homeless Veteran at a Diner, Until He Makes One Phone Call and Ends Their Career

A quiet Tuesday morning at a small-town diner turns into a national conversation when two officers confront a homeless veteran over nothing more than a cup of coffee. They thought he was just another man down on his luck—but they were wrong. One calm phone call changed everything. This is the real story of Clarence Dupri(e), a man the world tried to ignore… until it couldn’t anymore. What begins as a tense moment of profiling reveals a powerful truth about dignity, service, and what respect really looks like.

He was just trying to eat breakfast until two cops tried to humiliate him. Then he made one phone call that changed everything.

It’s just past 8:00 a.m. on a gray Tuesday morning in Mon, Georgia—the kind where the sky feels like wet concrete and even the streetlights don’t seem fully awake yet. On Vineville Avenue, there’s a tiny no‑frills diner tucked between a dry cleaner and a pawn shop. The kind of place where the coffee is never great, but the people make it worth sitting down.

Clarence Dupri sits there already, back against the wall, seat by the window. Same booth every week. His army jacket is older than the dishwasher in the back, frayed at the cuffs and faded near the shoulders, but still clean. His beard is scruffy but trimmed. He smells like black coffee and rolling tobacco—the kind you twist yourself with a little too much paper. He doesn’t talk much, but when he does, it’s always with respect.

“Morning, Mr. Dri,” says Carla the waitress. She’s early thirties, two kids, and runs the floor like a traffic cop with a smile.

“Hey, Carla, you got any more of that peach cobbler today?”

She laughs. “You know we don’t start that till lunch. You want your usual?”

Clarence nods. She doesn’t need to ask what that means: scrambled eggs, grits, two strips of bacon, and toast if it’s not burnt. Coffee—no cream, no sugar. Always the same.

Behind the counter, Harold, the owner, glances over his glasses. “That man could run this place better than me with one hand behind his back,” he says to Carla under his breath.

“He’s the only reason I don’t walk out of here some days,” Carla replies.

To most customers walking in, Clarence looks like someone barely holding on. No car, no permanent address, one pair of shoes that have seen better decades. But to the people who matter inside this little diner, he’s family—a quiet one, sure, but one they trust.

Clarence sips his coffee slowly, eyes scanning the news on the TV above the counter. There’s a story about veterans not receiving their benefits. He doesn’t flinch—just exhales slow through his nose and looks back out the window.

Outside, traffic starts to pick up. Students headed to Mercer. Parents dropping off kids at school. Folks trying to beat the rush to Robins Air Force Base. Nobody sees the black‑and‑white cruiser pull up right away. No speeding, no sirens. Just two officers stepping out like it’s routine. Maybe to them it is.

Officer Langley—tall, built like he played college ball twenty years ago and never got over it—opens the door. His partner, Officer Ree, short and square‑faced with a clipboard under one arm, follows close behind. They walk in like they’ve done it a hundred times—because they have.

Carla sees them first and forces a smile. “Morning, officers—usual table?”

They don’t answer. Langley’s eyes are already fixed on Clarence.

“Sir,” he says, walking over. “You a customer here?”

Clarence blinks once, slow, then nods. “I am.”

“You buy anything?” Ree asks.

“Coffee. Breakfast on the way.”

Langley glances at the counter. “You got a receipt?”

Carla steps in. “He’s fine. He’s here all the time.”

Langley doesn’t look at her. “Did I ask you?”

Carla’s mouth opens, but Harold raises a hand from the back. “Don’t, Carla,” he says softly.

Clarence doesn’t move, doesn’t raise his voice, doesn’t flinch. “I paid. She took the order. You can ask her.”

Ree squints. “You carrying ID?”

Clarence leans back, slow, reaches into his inside jacket pocket, and pulls out an old leather wallet, edges cracked. He slides over a VA card.

Langley takes one look and scoffs. “This all you got?”

“It’s all I need.”

Ree gives a short laugh, like Clarence just told a joke only he finds funny. “Yeah? We’ll see.”

But before they even ask him to leave, the diner falls quiet and a pressure starts building—the kind that tells you something’s about to go real wrong, real fast.

Ree steps in closer, arms folded like he’s sizing Clarence up for a mugshot. “How long you been here?” he asks.

Clarence looks up at the clock on the wall. “About thirty minutes.”

Langley tilts his head. “And how long you planning on staying?”

Clarence’s eyes narrow just a little, but his voice stays calm. “Long enough to eat my breakfast like everyone else.”

Carla slides the plate onto the table, trying not to make it look rushed. “Here you go, Mr. Dupri.”

“He already ordered?” Langley raises an eyebrow.

Carla doesn’t back down this time. “He comes in every Tuesday, pays cash, always polite. He’s a regular, sir.”

Ree turns back to Clarence. “You homeless?”

Clarence nods slowly. “I don’t have a house, no. But I got a home in this town.”

Langley smirks. “You got smart answers, huh?”

Clarence says nothing. He picks up his fork as if that’ll make them go away, but it doesn’t.

“You see, this is the problem,” Langley says, looking around like he’s addressing a crowd. “People think they can just camp out wherever they want, take advantage of kind folks like you all. That fair to everyone else in here?”

Nobody answers. Nobody wants to make it worse. A couple at the next table look down at their plates. A delivery guy waiting on a pickup shifts awkwardly near the door, but nobody says a word.

Clarence cuts a piece of egg, chews, swallows, wipes his mouth with the napkin. “I served in Iraq twice. Came back, worked security in Alabama until my knees gave out. I get by. I don’t steal. I don’t beg. I pay for my food. So why are you talking to me like I broke into somebody’s house?”

Langley chuckles, but there’s no humor in it. “Relax. Just doing our job—making sure everything’s in order.”

Carla steps forward again, eyes sharp. “Then check the register. He paid. I rang him up. What else do you need?”

But Langley ignores her. Ree pulls out a little notepad. “Name?” he asks.

Clarence raises an eyebrow. “It’s right there on the card.”

“I asked for your name out loud,” Ree repeats.

Clarence sighs. “Clarence Dri.”

“Date of birth.”

“February tenth, 1968.”

Langley looks at Ree. “Run it.”

Ree walks back toward the cruiser, muttering something under his breath.

Harold finally steps out from behind the counter, wiping his hands on a towel. “Officers, can I talk to you outside a moment?”

Langley waves him off. “We’re good, sir.”

“No, you’re not,” Harold says, firmer now. “That man has never caused trouble in my business. You got an actual reason to be here, or are we just harassing veterans now?”

Langley finally turns to him. “Sir, we’re responding to a complaint.”

Harold frowns. “From who?”

Langley doesn’t answer. He just shifts his weight from one foot to the other and keeps watching Clarence like he’s waiting for him to mess up.

Clarence finishes a bite of toast and pushes his plate slightly forward as if to show he’s done. He wipes his hands on the napkin and reaches into his jacket again. This time he pulls out a scratched‑up flip phone—the kind nobody uses anymore, except maybe someone like him.

“What’s that?” Langley asks, already sounding on edge.

Clarence flips it open with one hand, presses a number on speed dial, waits.

“Clarence—” Harold leans in.

But Clarence just raises one finger as the line clicks. He puts the phone to his ear. Pause. Then, calm as ever, he says, “It’s happening again.”

And just like that, everything in the room shifts. No one knows what that call means, but the silence it leaves behind is loud enough to rattle the windows.

Langley narrows his eyes, watching Clarence like he just pulled a pin on a grenade. “Who the hell did you just call?”

Clarence doesn’t flinch, doesn’t answer. Instead, he calmly closes the flip phone, sets it on the table next to his plate, and leans back.

“You said you were just doing your job,” Clarence says—voice low, steady. “Now I’m doing mine.”

Langley steps forward, puffed up now, hands on his duty belt. “Sir, I’m going to need you to stand up and come outside with me.”

Harold’s had enough. “No, he’s not going anywhere. Not unless you’re arresting him.”

Ree returns from the car holding a tablet. “Name checks out,” he mutters, scrolling. “VA database confirms veteran status. Honorable discharge. Two tours. Bronze Star.”

Langley doesn’t even blink.

“He homeless?”

“Yeah—no fixed address. Was cited last year in Albany for loitering.”

Langley nods like that’s the only confirmation he needed. “Then he’s a drifter. Doesn’t belong sitting here all day taking up space.”

Carla slams her notepad down on the counter. “You’ve got regulars who sit for hours sipping one cup of coffee and nobody says a word—but you come in here and go after the one man who actually earned that right.”

Langley points at her. “Ma’am, I’d advise you to step back.”

“You don’t get to advise me in my own workplace,” she snaps.

Clarence stays seated—calm, still—but his fingers drum the edge of the table once, twice, three times. He doesn’t look angry, just tired. The kind of tired that gets in your bones and never leaves.

“You see me as a problem,” he says to Langley, “but I’m not the one making a scene.”

Langley finally snaps. “That’s it. Stand up—now.”

Clarence slowly rises to his feet, taller than he seemed when sitting. Straighter, too. He looks Langley in the eye. “I don’t want trouble.”

Langley reaches for his cuffs. “You should’ve thought about that before you got clever.”

Before he can grab Clarence’s wrist, the front door swings open so fast the bell above doesn’t even jingle right. It just slaps against the wall and bounces back. A man walks in—mid‑forties, smooth navy suit, dark overcoat. No badge on his chest, but authority in every step. He moves with purpose, straight toward the table, without pausing to look around. He holds up a black leather ID case.

“Assistant Director Mark Sorrell, Department of Justice.”

Langley freezes, hands still halfway to the cuffs.

Sorrell’s voice is crisp, calm, lethal. “Officers, I’m going to need your badge numbers. Now.”

Ree stumbles. “Uh, sir, we were just responding to a—”

“There was no complaint,” Sorrell cuts in. “We monitor certain keywords on open radio lines. You’re both recorded. Both of you were violating departmental protocol the moment you started questioning a civilian without cause. This man is a veteran, not a suspect.”

Langley’s face flushes red. “With all due respect, you’re not our supervisor.”

“No,” Sorrell says. “I’m your investigation.”

Clarence doesn’t say a word—just sits back down, smooth and slow, like none of this surprises him.

Harold exhales through his nose, long and deep. Carla’s eyes are wide, flicking between the men like she’s watching a courtroom drama on daytime TV. Langley looks around the room, realizing everyone’s watching. Everyone heard. Everyone saw. And there’s nothing he can do now.

The worst part for those officers? The camera on Ree’s chest is still rolling, and what it’s captured is more than enough to change everything.

Sorrell doesn’t sit, doesn’t smile, doesn’t raise his voice. He doesn’t have to. “I suggest you both step outside. Now.”

Langley and Ree hesitate like boys caught doing something they know their mama wouldn’t approve of. Eventually they walk out without another word, heads down, shoulders tight. The diner stays quiet, but it’s not peaceful. It’s the kind of silence that watches.

Clarence reaches for his coffee—still warm. Sorrell stays standing beside the booth, hands behind his back. He leans in just slightly, voice low enough only Clarence can hear.

“You all right?”

Clarence nods. “Didn’t want to call you.”

“I know,” Sorrell replies. “But you were right, too.”

Carla finally finds her voice. “Wait—what just happened? Who is he?”

Clarence glances up at her. “Friend from the old days.”

Harold crosses his arms. “You got friends who walk in with a DOJ badge and shut down cops mid‑complaint?”

Clarence gives the faintest smile. “Depends on the complaint.”

Sorrell turns to Carla and Harold. “I apologize for the disruption. We won’t be long. I need a few minutes with Mr. Dupri.”

Harold nods. “Say what you need. Coffee’s on the house.”

Clarence shakes his head. “Put it on me. I always pay.”

Carla gives him a small smile. “Of course you do.”

Sorrell sits across from him. His tone shifts—less official now, like he’s talking to an old war buddy, which he is.

“You sure you’re okay?”

Clarence shrugs. “I’ve had worse mornings. I’ve had better, too.”

“This the third time this year, Clarence.”

“Yeah.”

“You want me to push this up the chain?”

Clarence doesn’t answer right away—just folds his napkin neatly and places it beside his empty plate. “Do what you gotta do. I’m tired of explaining myself to people who already made up their minds.”

“You shouldn’t have to,” Sorrell says. “Not after what you gave up for this country.”

Clarence’s face hardens for a second. “They only care about that when I’m in uniform. Not when I’m sitting in a diner trying to eat.”

“They’ll be suspended—at the very least.”

“I don’t want apologies,” Clarence says, calm. “I want respect. I want them to learn something that sticks.”

Sorrell pulls out his phone. “The body‑cam footage will be flagged and reviewed today. You’ll get an official call from internal affairs—probably two interviews. Then we’ll notify the press.”

Clarence doesn’t flinch. “Let them see it. Maybe next time they’ll think twice.”

Outside the diner window, Ree paces by the patrol car, arms crossed. Langley’s on his phone—face stormy and pale all at once. Inside, Carla is back to refilling cups, but every few seconds, her eyes flick to Clarence. She’s never seen this side of him. No one here has. And that’s the thing about people like Clarence: they don’t brag. They don’t yell. They just carry more than most—in silence.

Sorrell rises. He places a business card face‑down on the table. “You call that number if anyone else tries anything. You understand me?”

Clarence nods. “I appreciate you.”

“The people that matter do.”

But outside, something’s brewing. And what Clarence doesn’t know yet is that the worst is still coming—and it’s not from the officers. It’s from the internet.

Two hours later, the diner is back to its usual rhythm. Coffee cups clink. Forks scrape plates. The low murmur of morning conversation hums beneath the crackling radio near the register. But something’s different. It’s not just that Clarence is still sitting in the same booth; it’s the way people glance at him now—longer, curious, respectful, hesitant.

Carla leans in while refilling his coffee. “You sure you want to stick around? You got half the city whispering already.”

Clarence shrugs. “I didn’t do anything wrong.”

Harold grunts from behind the counter. “You didn’t. But folks don’t care about facts—they care about drama.”

Clarence takes a sip. “Then they better bring their own cup. I’m not pouring it.”

That gets a small chuckle out of Carla, but it doesn’t last long. The bell above the door rings again. This time it’s not a cop, not a customer. It’s a teenage girl in a hoodie and sweatpants—phone glued to her hand.

“You him?” she asks, stepping toward Clarence’s booth without hesitation.

Clarence looks up, confused.

“You’re the guy from the video, right? The veteran at Henry’s Diner.”

Clarence frowns. “How do you—?”

“It’s all over TikTok. Somebody posted the body‑cam footage, tagged the location. It’s everywhere. My brother’s in college and he saw it.”

Clarence leans back, jaw tight. “That was fast.”

“Fast?” She laughs, incredulous. “You’re trending, man. People are pissed. Those cops—Twitter’s eating them alive.”

Harold walks over, brow furrowed. “Wait—who posted the footage?”

“Don’t know, but it’s got over four hundred thousand views in like two hours.”

Carla puts a hand on her hip. “What exactly does the video show?”

The girl scrolls and turns the screen. “Here. Look.”

On the tiny screen, Ree’s body‑cam flickers to life. You can hear Langley asking Clarence for ID. You can hear Carla trying to speak up. You can see the moment Langley reaches for his cuffs and then Clarence quietly pulls out his phone and makes the call. Then Sorrell’s arrival. It plays out like a scene in a movie.

Clarence looks away. He doesn’t like watching himself on screens. Feels like being peeled open in front of strangers.

“People are calling you a hero,” the girl says. “Like silent‑warrior kind of hero. There’s even a hashtag—#ClarenceDri.”

Clarence shakes his head. “I’m not a hero.”

“You’re not invisible anymore,” she says softly. Then she walks out just as quick as she came in.

Carla pulls out her phone, taps around, then looks at Clarence. “She’s right. You’re all over. There’s articles popping up. Even a reporter from Savannah is asking for an interview.”

Clarence sighs. “That’s not what I wanted.”

“You sure?” Harold asks. “Because maybe it’s what we needed—people finally seeing what’s been happening right under their noses.”

Clarence doesn’t answer. He looks down at the VA card still sitting on the edge of the table. That little piece of plastic never got him a job. Never got him an apartment. Never even got him a thank‑you when he needed it most. But now—now it’s viral content. And that feels complicated.

Behind the scenes, bigger forces are waking up. Because when the internet gets involved, stories don’t just spread—they explode.

By noon, Clarence’s name isn’t just floating around social media; it’s running across the bottom of national news tickers. Local station WRBL picks up the footage, calling it another example of unchecked authority. CNN runs a short segment before lunch. By evening, the video’s been clipped, stitched, remixed, and dissected by every online pundit with a webcam and an opinion.

People want to know who this quiet, steady man is, where he came from, what he’s been through, and how two local cops got so comfortable disrespecting him in broad daylight. They start digging—and that’s when the truth about Clarence Dri starts coming out.

It begins with an old photo—black‑and‑white, grainy, taken somewhere in Fallujah. Clarence standing beside two other men in full combat gear, sand crusted on their uniforms, rifles slung over their shoulders, exhaustion in their eyes. The caption reads: “Co‑operative Clarence Dupri, Task Force Wolfhound, 2006.”

The internet doesn’t know what Task Force Wolfhound is, so they dig deeper. Turns out it was a covert joint‑operations unit that handled hostage recovery missions—classified work. Most of their files were sealed, but veterans talk quietly, respectfully, and when one of them shares a redacted commendation letter addressed to Clarence—dated 2007—the story breaks wide open.

This wasn’t just some regular grunt. Clarence Dri had saved people. Not once, not twice—dozens of times. There are no interviews with him on record, no medals hung on any wall, no speech or ceremony—just a paper trail of excellence hidden in silence.

Back in the diner, Clarence doesn’t have a clue how far things have gone. He doesn’t do Twitter. Doesn’t care for TikTok. He’s sitting in the same booth flipping through a local newspaper that doesn’t even have the story yet.

Sorrell calls again. “You might want to prepare yourself.”

“For what?” Clarence asks.

“The phones are ringing off the hook—congressional offices, newsrooms. A few big‑name vets from D.C. want to shake your hand. Some nonprofit even wants to buy you a house.”

“Buy me a house?”

“Yeah. You’re the internet’s newest hero.”

Clarence laughs under his breath. It’s not joy—it’s disbelief. “All I did was sit down for breakfast.”

“No,” Sorrell says. “You stood up without standing up.”

Clarence looks out the window. The world feels like it’s speeding up without asking if he wanted to come along. He doesn’t like being the center of attention. He spent years trying not to be noticed. But now strangers are turning him into a symbol—some for justice, some for contempt.

Carla slides a small box onto the table. “Someone from the VA center dropped that off for you.” Inside: a clean button‑up shirt, a pair of new boots, a prepaid phone, and a note that just says, Thank you, Sergeant Dri.

Clarence stares at it a long moment. He doesn’t need gifts. He needs peace. But maybe this is the cost of making the world look at something it’s ignored for too long.

“Harold,” Clarence says quietly. “You ever feel like people don’t see you till it’s too late?”

Harold doesn’t look up from the register. “Only every damn day.”

The video doesn’t fade like most trending clips. It grows. By Thursday morning, the Mon Police Department issues a formal statement: We are conducting a full investigation into the incident involving Mr. Clarence Dupri. But the internet doesn’t want a statement. They want action. They want names—and they already have them. Within hours, Officer Ree deletes his social media accounts. Officer Langley tries to go private, but not before someone screenshots his Facebook comments from years ago. Some of it’s bad. Real bad. The kind of stuff that makes you wonder how he ever wore a badge to begin with.

Protesters gather outside department headquarters. Not thousands, not even hundreds—just enough to fill a sidewalk. A quiet line of folks holding signs that read I am Clarence Dupri. No chants. No screaming. Just presence. That’s all it takes.

Journalists peel back the layers. Turns out this wasn’t Langley’s first complaint for profiling—or even his fifth. There were reports filed and forgotten. Citizens who didn’t know who to call. Letters that never reached the right desk. But Clarence did—and his one call shook the entire tree.

At the diner, things change. Carla’s been interviewed twice. Harold’s photo is on a local blog. Customers show up just to sit in the booth Clarence was in. One guy even asks to take a selfie with the chair.

“I’m not an attraction,” Clarence mumbles.

“You’re a mirror,” Carla replies. “People just don’t like what they see when they look in.”

Still, Clarence doesn’t feel like a hero. Heroes get rest. They get safe. He’s still sleeping in the same shelter, still folding his jacket into a pillow at night, still stretching old pain out of his knees every morning. But something’s different now.

One evening a van pulls up outside the shelter. Two men in suits get out and ask for Clarence. They hand him an envelope. Inside is a letter from the Secretary of Veterans Affairs. It apologizes for how he’s been treated—offers an expedited housing voucher, a counselor, a caseworker, access to a therapist.

“I didn’t ask for this,” Clarence says, holding the letter like it’s a riddle.

“No, sir,” the younger man says. “But you earned it that night.”

By Friday, the officers are suspended. The mayor of Mon gives a press conference. The chief of police stumbles through an apology that sounds like it was written by lawyers—but it doesn’t matter much. Public pressure does what bureaucracy never could. Ree resigns. Langley refuses. But with the investigation heating up and more old cases being re‑examined, his badge is hanging by a thread. Even the union knows he’s dead weight now.

Clarence watches it all unfold from a bench outside the shelter. There’s a camera crew waiting nearby, but he’s not interested—not today. He lights a cigarette. He doesn’t usually smoke, but some days just call for it.

An older woman walks by, recognizes him, and pauses. “Thank you,” she says.

Clarence doesn’t ask for what. He just nods—because maybe finally people are starting to understand something he’s known for years. Respect isn’t something you give to people like him out of pity; it’s something they deserve. And if it took one phone call, one diner, and one bad morning to teach that lesson—so be it.

But there’s still one thing left to say, and Clarence knows it won’t come from a press release or a protest. It has to come from him.

The following Sunday morning, the diner’s unusually quiet. No cameras, no news vans—just the regulars again. Locals who come for Harold’s eggs and Carla’s gossip, the ones who were here before the headlines and will be here long after they disappear.

Clarence walks in wearing that same army jacket. But now his posture is different—not stiff, not proud, just present. Like someone who knows exactly where he stands, even if the ground beneath him keeps shifting.

Harold nods toward his usual booth. “It’s open.”

Clarence doesn’t sit. He clears his throat. For a moment, nobody notices. Then Carla sees him. “Mr. Dri?” she says, setting down a tray.

“I got something to say,” Clarence replies, eyes scanning the room.

The diner quiets.

“I’m not a hero,” he starts. “I didn’t plan to be a story. I came in for eggs and coffee like always—like I have every Tuesday for years.” He looks at Harold, then Carla. “Y’all saw me not as a problem, not as a project—as a person.”

He turns to the others. “But some folks—they didn’t. And maybe now that video got out, people are paying attention. That’s good. But attention isn’t the same as understanding.”

A few heads nod. One man lowers his fork.

“See,” Clarence says, tapping his chest lightly. “I wore this jacket in the desert. I watched men I loved die in the dirt for a country that forgets us the moment we take off the uniform. I didn’t ask for praise. I asked for a seat. I didn’t demand a parade—just a plate.” He pauses. “And still, I had to prove I belong.”

Clarence steps forward, facing the room. “There are thousands like me. You won’t see them on the news. You won’t hear their names. Some are homeless. Some are working jobs with bad knees and broken backs. Some just stopped talking ’cause they got tired of being invisible.” He holds up a hand. “But hear this: being poor isn’t a crime. Being tired isn’t a weakness. And asking to be treated like a human being should never be met with suspicion.”

Carla wipes her cheek—tries to make it look like she’s just rubbing her eye. It doesn’t work.

Clarence smiles gently. “We all walk into places carrying stories no one sees. So the next time you see someone who looks like they don’t belong, maybe they do. Maybe they belong more than you know.”

He nods once and finally takes his seat. Nobody claps. Nobody needs to. Sometimes the truth is loudest when it’s quiet.

The rest of the morning, folks come and go. Some leave cash on Clarence’s table without a word. One woman hands him a handwritten letter and walks away. Harold brings him another coffee without asking.

That afternoon, Clarence walks over to the shelter one last time. He packs his things. The apartment key from the VA is cold in his hand—strange, heavy.

Later that week, the first news story fades; then the next. Social media finds someone new to rage over. The world moves on. But Clarence doesn’t. He plants roots in a neighborhood that sees him; in a place where people knock on his door not to question him—but to say hello. He starts volunteering at a nearby school, speaking to kids about service, about silence, about dignity. The staff don’t quite know how to introduce him, so they don’t. They just say, “This is Mr. Dupri. You’ll want to hear what he has to say.”

Because it turns out people listen now. But more importantly, they look—and they see.

Let this story be a reminder. Not every hero wears a cape. Some wear jackets older than you. Some sit quietly with coffee. Some fight battles you’ll never hear about. Respect doesn’t come after you’re gone. It should come while you’re still here. So the next time you cross paths with someone who looks forgotten—speak, don’t stare. Listen, don’t assume. And when you can, stand up—even if it’s just by sitting down beside them.

Extended Edition — Aftermath, Origins, and Reckonings

Before the Diner

Clarence Dupri grew up in a single‑story house the color of dried clay on the far edge of the county line, where the mornings carried the sound of freight trains and the nights were stitched together by dogs and cicadas. His mother worked the register at a grocery that changed owners every other year; his father hauled lumber until his back refused to listen. Clarence learned early that quiet could keep a boy safe and that respect, once earned, didn’t need to be announced.

He was eighteen when the recruiter pinned a brochure to the kitchen corkboard. “You got patience,” the man said. “That travels.” It did. Clarence signed, shaved his head, and folded his life into a green duffel bag that smelled like canvas and metal. He shipped to basic and discovered that the silence he wore like a coat could steady a whole squad. Men shot better when he breathed slow. They moved smarter when his voice stayed level. He wasn’t the loudest; he was the hinge everything swung on when doors came off.

Between deployments he mailed paychecks home and built a habit of carrying other people’s weight. His knees learned it. His back learned it. His heart learned it most.

Wolfhound

Officially, Task Force Wolfhound didn’t exist on any map a civilian could find. Unofficially, it was a braid of soldiers, intel, and duty lawyers who understood how thin the line can feel between necessary and wrong. In the heat that turned metal into mirrors, Clarence learned the patience of the long wait and the speed of the short window. A door bangs; a life changes.

On a winter morning outside Fallujah, the team rolled to a cinderblock compound where a kidnapped engineer had been moved hours earlier. Clarence took rear security, which meant the lives behind him counted on his steadiness the way lives in front counted on someone else’s speed. The breach blew chalk into the air; the room bloomed into noise; and then, just like that, the mission bent sideways when the engineer’s kid—nobody knew there was a kid—ran from behind a curtain. The plan didn’t have a line for that. Clarence did. He dropped his muzzle, scooped the boy with his left arm, kept his right hand on his sling, and walked backward through a fog of dust and confusion until the door found them. It was two minutes of math no one rehearses. Later, when the air cleared and the engineer was found alive, a captain he didn’t like much handed him a folded letter that said commendation without saying hero. “We don’t talk about it,” the captain said. “We just remember.”

They remembered. The files remembered. Clarence didn’t ask for anything more.

Homecoming

The first day back in Georgia tasted like rain and diesel. Clarence’s mother had kept his childhood blanket; his father had kept the habit of turning on the porch light at dusk. Clarence kept the knee brace the medic insisted on and a quiet he couldn’t shake. He worked security in Alabama until the overtime he needed turned into the limp he couldn’t hide. The VA line moved like honey in January. “We’ll call you,” they said, and sometimes they did and sometimes the phone forgot how to ring.

He learned how to sleep in shifts again. Shelters have their own rhythms; you learn which cot squeaks and which door hinge whistles. He kept a clean jacket and a pocket full of names that didn’t know what to do with him. Most mornings he walked to Henry’s Diner because coffee doesn’t judge and Harold knew when to leave a man alone.

Sorrell

Mark Sorrell was the kind of lawyer who never forgot he started as a public defender with a suit two shades lighter than the rent. In Iraq he’d worn a different badge—Department of Justice, legal liaison—and his job had been to translate chaos into evidence sober enough to stand up in court. He met Clarence at a forward operating base where the coffee tasted like the inside of a tin can and the printer jammed every third page. Sorrell watched how Clarence stood in briefings—shoulders easy, eyes awake, never reaching for drama when gravity would do. “If I ever need you stateside,” Sorrell had said once, handing over a card, “you’ll know when.”

Years later, when a gray Tuesday in Mon reminded Clarence that some uniforms come with assumptions, the card still lived behind his VA ID. Speed dial 2. It had been 1 once, back when his parents were alive.

The Investigations

Internal Affairs scheduled the first interview for the following Wednesday. A conference room with a crooked flag and a coffee maker that was never cleaned right. Clarence took the seat nearest the exit—habit—and folded his hands. Two investigators walked him through the script: “For the record… Is this your statement… Did any officer touch you…”

He answered clean. “They asked for a receipt before they asked for my name. They asked if I ‘belonged’ instead of asking if I needed anything else. The waitress told them I was a regular. They ignored her.”

They asked why he made the call. He nodded at the recorder. “Because sometimes the only thing a man can do is call someone who will write down what happened and not pretend it didn’t.”

The POST council—the state board that decides who gets to keep wearing a badge—met a month later in a room that smelled like carpet shampoo. Langley arrived with a union lawyer who spoke in the soft voice lawyers use when the file in front of them is worse than what they’re saying out loud. The board asked about prior complaints. There were more than a few. They asked about policy: when a receipt is a pretext; when an ID request becomes a fishing trip; when discretion turns to discrimination. Langley said he was “ensuring business peace.” The board said the business had already said peace was fine. No one said profiling because sometimes the word people avoid is the only one that fits.

Ree resigned two days before the vote. Langley didn’t. The board decertified him anyway. Clarence heard about it from a reporter he didn’t call back.

Viral Weather

The internet behaves like a storm front: builds quietly, breaks loudly, leaves branches down you don’t notice until you trip. For every message that said thank you, Clarence read three he shouldn’t have, because curiosity is a muscle and the modern world keeps it overtrained. People told him what he was. Hero. Liar. Pawn. Saint. Fraud. Some posted screenshots from years that had nothing to do with him; some posted theories like scaffolds nobody checked for weight. Carla banned phone filming in the diner unless folks asked first and meant it. Harold put up a sign that said NO POLITICS. YES PANCAKES. It helped until it didn’t.

Sorrell texted once: Step back from the comments. Not every voice deserves your ears.

Clarence put the prepaid phone in a drawer and left it there for three nights. He slept better.

The Apartment

The VA voucher turned into a key with a blue tag and an address that sounded like a real place: Maple Commons, Building C. The manager walked him through the lease like it was a hymn. “No smoking inside. Package lockers downstairs. Laundry takes quarters you can reload with the app if you like.”

He put the new boots still in their box under the bed and the old army jacket on a hook near the door. The first night, the quiet felt different. He turned the TV on with no volume just to borrow movement. In the morning he made coffee in a machine that didn’t know how strong he liked it yet and opened the blinds so the sun could find out who lived there now.

He took a bus to the shelter anyway. You don’t leave places; you thank them. He sat with men whose stories dipped and rose in the middle like bridges that never learned to be straight. They asked about the video. He said it was loud and then quiet again. He asked about their paperwork. One man needed a copy of a discharge he’d lost somewhere in three states. Clarence wrote down the number for the county veterans service office and told him to ask for Ms. Parson because she listened. He rode home with the window cracked and didn’t mind the wind.

The School Gym

The principal introduced him as “Mr. Dupri, a veteran who knows a little about dignity.” Seventh‑graders fidgeted in bleachers that had carved their initials out of boredom for years. Clarence looked at a sea of faces that hadn’t learned yet how heavy other people’s opinions could feel in a pocket.

“You don’t owe anyone your volume,” he said. “You owe them your truth. Those are not the same.” He told them about the diner without telling them about the comments. He told them about a rescue that happened faster than a thought and about a coach who once told him to tie his laces twice because the second knot is the one that keeps you honest. He said sometimes courage is a hand on a shoulder and sometimes it’s a hand staying at your side when somebody wants to pull it where it doesn’t belong.

A boy in the front row asked if he was scared when the officers walked in. “Yes,” Clarence said. “And hungry. Both can be true.” The gym laughed the way a room laughs when it needed permission.

Harold and Carla

Harold added a Tuesday special quietly: Dupri’s Plate — eggs, grits, bacon, toast (not burnt). He didn’t point at the menu box when people asked. He pointed at the booth and said, “That’s a person’s name, not a plate.” Carla learned to say no like a doorman when bloggers asked to film in her section. She started a jar behind the register for the shelter’s dental fund because, as she told anyone who would listen, “pain chews dignity faster than hunger.”

On slow afternoons, Clarence helped restock napkin dispensers and learned that ketchup bottles have a way of hiding from busy hands. Carla learned he liked the corner of his toast cut off when it browned too dark and that he read the paper starting from the back because box scores calmed him down.

The Letter He Wrote and Never Sent

Officer Langley,

You don’t know me, though you think you do. You saw a jacket and made up a file. That happens. I’ve done it. The mind likes shortcuts when it wants to feel safe. But your shortcut made a mess of a room full of people who came for breakfast. You turned a plate into proof. You forgot to ask what it was proof of.

If we ever share a room again, I hope it’s because we both walked in to apologize to someone we’ve never met. You can talk to me about bad days. I’ve had worse ones. You can talk to me about fear. Mine speaks plain. What I won’t tolerate is smallness. Your badge is heavy; don’t wear it like it’s light.

— C.D.

He folded the paper and put it in the back of his dresser like an old scar you don’t show to new friends. Some things heal better when they stay yours.

What Respect Looks Like

Respect looks like Harold bringing a second napkin before he’s asked. Like Carla saying, “Sit as long as you like,” when the lunch rush is already leaning on her feet. It looks like Sorrell answering on the first ring even when the city outside his office windows is loud with its own emergencies. It looks like a VA clerk who says, “I don’t know, but I’ll find out,” and means both.

It also looks like saying no to the wrong attention. Clarence turned down a segment on a show that traded in outrage for ratings and a sponsorship that wanted him to wear a jacket he wouldn’t recognize himself in. He said yes to the school gym and to a roundtable at the city library where the flier read: Dignity: A Conversation, Not a Clap. Ten people came. It was enough.

The Booth on a Quiet Sunday (Reprise)

A month after the first quiet Sunday, Clarence asked Harold for pancakes—something he’d never ordered. “You celebrating?” Harold asked.

“Breathing,” Clarence said.

Carla poured coffee without asking. The bell above the door worked just fine. No cameras. No speeches. The world outside still argued with itself, as it always had. Inside, forks found plates and a toddler babbled a language Clarence didn’t speak but understood all the same: I am here. See me. Be kind.

He looked at the window where his reflection sat layered over the street. For once, he liked the way the two images agreed. He lifted his cup toward the glass and toward the room.

“To the next person who needs a seat,” he said softly.

Harold, wiping a plate dry, heard him anyway. “Always got one here.”

Epilogue: The Call, Defined

People kept asking who, exactly, he had called. Some thought it was a senator. Some thought it was a news anchor. Clarence never corrected them in public. In private, he answered straight: “I called a man who promised me once that if I ever needed someone to listen before things got loud, he would. That’s all.”

He kept Sorrell’s card, but he also kept a second one now—Ms. Parson’s, the county VSO who found a way to cut through a knot of forms with patience instead of scissors. “Call this one first,” he told the men at the shelter. “Then the other if you need the kind that carries a bigger hammer.”

Sometimes the best phone calls don’t end anyone’s career. They start one—the kind that rebuilds trust one Tuesday at a time.

POST Council — A Matter of Retention

The hearing room was carpeted in the color of caution and lit like a waiting room. A brass placard on the table read PEACE OFFICER STANDARDS AND TRAINING COUNCIL; a paper pitcher sweated beside styrofoam cups. Clarence chose a chair by the wall and watched the choreography: union lawyer at one end, city attorney at the other, a recorder’s red light steady as a heartbeat.

The chairwoman spoke in sentences that sounded like doorframes: square, load‑bearing. “We are considering whether Officer Langley remains fit to hold certification under O.C.G.A. § 35‑8‑7.”

A board member read from policy: Pretext at point of service without predicate behavior may constitute harassment. Another asked about the receipt request—why it had become a condition for presence. The union lawyer said “business peace.” The city attorney said the business itself had declared peace.

They queued the body‑cam. The room listened to the hush of a diner turned courtroom: Carla’s steady insistence; Harold’s strain; the clatter of a fork when someone at the next booth forgot how to hold one. They watched a man in an army jacket dial a number without raising his voice.

“Officer,” the chairwoman asked, “what articulable suspicion justified this encounter?”

Langley swallowed. “We had a complaint.”

“From whom?”

He didn’t answer. The recorder caught the silence and filed it like evidence.

The vote was seven to zero. Decertified. Ree had resigned two days earlier. No one applauded. Rooms like that don’t do applause; they do outcomes.

The Library Roundtable — Dignity, A Conversation, Not a Clap

The city library’s community room had the soft echo of places built to hold questions. Ten chairs made a circle: a pastor in a collar flecked with lint; a nurse on night shifts; a high‑school junior who filmed everything except his own awkwardness; a retired mail carrier who refused to sit with her back to the door; Harold with an apron in his tote; Carla on her break; Ms. Parson from the county VSO; Sorrell on video, a square in the corner of a borrowed projector; and Clarence, jacket zipped to the throat despite the warmth.

“What do you want from people who will never see the inside of a shelter?” the pastor asked.

“Less advice,” Clarence said. “More eye contact.”

The nurse asked how to intervene without making a scene. Carla said, “You can make a scene that isn’t a show. Ask, ‘Is everything okay at this table?’ Loud enough for policy to hear you.”

The junior asked if going viral helps. Sorrell’s rectangle shook his head. “It helps for three days. Then it asks what you’re selling. Make your moment buy something that lasts—policy, training, a phone number that works.”

Ms. Parson slid handouts across the table: HOW TO GET A COPY OF YOUR DD‑214 and Expedited VA Contacts (County List). The mail carrier read every line like she wished the world came with instructions more often.

“I used to think respect was a medal,” Harold said. “Turns out it’s a napkin you bring before someone has to ask.”

Clarence listened more than he spoke. When he did, he said, “What I want is for the next person to sit down without a lecture attached.” The room wrote it down as if the line had somewhere more important to be.

Memorandum on Practice — Excerpt (Public Release)

Department of Justice

Civil Rights Division

Subject: Observed Patterns in Point‑of‑Service Encounters Involving Non‑Housed IndividualsFindings (excerpt): The receipt request, absent predicate conduct, has become a proxy for exclusion. Policies that allow staff testimony to establish purchase should be credited as sufficient absent contrary evidence. Training must emphasize that presence is not probable cause.

Action Items (excerpt): (1) Model policy language for participating agencies; (2) Scenario‑based training modules for private businesses; (3) A voluntary registry of businesses adopting No Pretext pledges.

Sorrell forwarded the memo to Harold, who printed it and taped it by the staff clock with blue painter’s tape. “Read twice, sign once,” he wrote beneath it in Sharpie.

Tuesday Training at Henry’s

They didn’t close for it. They never could. But Harold stacked two booths with laminated scenarios and ran the floor like a drill the way only service people can—soft, fast, precise. Carla role‑played a customer with a full cup and an empty welcome. “What do you do?” she asked the new kid from Mercer behind the counter.

“Offer a refill and a menu,” he said, tentative.

“And?”

“And ask, ‘Would you like anything else?’ like you mean it.”

“Good,” Carla said. “Policy is how you use your voice when you don’t have a badge.”

Harold added a line to the staff manual in all caps: RECEIPTS ARE NOT PROXIES FOR RESPECT. He added another in lowercase the way a kindness should look on paper: If a person needs to sit, they need to sit.

The Back‑Door Apology

It happened on a Wednesday that carried rain like it had nowhere else to be. Langley waited by the dumpster, hat in his hands, smaller than any uniform could make him look. Harold spotted him first and almost turned the deadbolt for the principle of it; then he didn’t, for the same reason.

“Mr. Dupri,” Langley said when Clarence stepped into the alley, steam from the kitchen curling between them. “I’m here to apologize.”

Clarence watched the rain bead on the brim. “You apologizing to me or to the cameras that didn’t show up?”

“To you,” Langley said, and the way the word landed told the truth better than anything else in the alley. “I had a script in my head I didn’t write, but I kept reading it.”

“Get a new script,” Clarence said. He didn’t move closer, didn’t move away. “And read it where it counts.”

Langley nodded. “I’m working at my brother‑in‑law’s shop now. No badge. It’s… different.”

“Hard,” Clarence said. “Different is always hard.”

Langley held out a folded paper that looked like it had been through three pockets and a washer. “I wrote this before I knew I would say any of it out loud.”

Clarence didn’t take it. “Keep it. Read it to your kid, if you’ve got one. Or to the next rookie you meet, if you ever wear a uniform again.”

Rain made a steady sound on metal. They stood in it until silence meant what it was supposed to. When Clarence turned back toward the kitchen, he said over his shoulder, “Don’t come in the front. Not today. Some rooms still need to decide what you mean to them.”

“Understood,” Langley said, and left by the way he’d come.

One Tuesday at a Time

The weeks learned each other’s names. Tuesdays grew a spine of rituals: the bell that behaved; the corner booth with a view of both door and window; Dupri’s Plate highlighted in a font Harold called hopeful because he didn’t know what else to call it. Ms. Parson stopped in some mornings with forms that needed a signature; she signed where she could and left the sticky notes where she couldn’t.

A kid from the shelter started showing up with a book on small engines tucked under his arm; Clarence quizzed him on torque and patience, which he said were cousins. The nurse from the roundtable brought blood‑pressure cuffs twice a month and called it coffee with numbers.

Sorrell sent fewer texts. When he did, they read like weather: Sunny on your side? Clarence sent back a picture of a half‑empty cup because some answers should always be pictures.

One Tuesday, a young soldier in crisp fatigues stepped in, cheeks wind‑raw, eyes too awake to belong to someone who had just finished breakfast formation.

“You Clarence Dupri?” the kid asked.

“Sometimes,” Clarence said.

“My sergeant said if I’m ever in Mon on a Tuesday, I should buy you a coffee and keep my mouth shut while you drink it.”

Clarence smiled without showing teeth. “Your sergeant’s trying to teach you three things at once. Sit.”

They talked about boots that fit and the way time moves on deployment—slow as a convoy until it isn’t. They talked about what to do with a hand that keeps shaking when there’s nothing to carry. Clarence taught him the trick of putting a quarter under a glass and trying not to let the ring rattle. “You can’t stop it,” he said. “You can only aim it.”

At noon the crowd thinned. Carla leaned on the counter like a cliff you could sit on. Harold pretended the griddle needed him more than the room did. A light rain started and failed to matter.

Clarence paid, as he always did. He folded the receipt and slid it under the sugar caddy as if it lived there. On his way out he straightened the NO POLITICS. YES PANCAKES. sign because principles deserve alignment too.

On the sidewalk he paused, took out the prepaid phone he barely used, and held it, not because he needed to make a call, but because the weight felt honest in his hand. He scrolled to 2. SORRELL and then past it to 1. PARSON, C. He locked the screen and put it away.

Some phone calls end careers. The better ones start conversations. The best ones never need to be made because a room remembers how to be a room without them.

Clarence pulled up his collar and walked toward Maple Commons. The jacket was still old. The key on the blue tag was still new. Between them, a Tuesday big enough to sit in.

News

“Not for Applause, But for Remembrance”: Adam Sandler’s Midnight Ballad After Charlie Kirk’s Death—and the Hushed Arena That Became a National Vigil

“Not for Applause, But for Remembrance”: Adam Sandler’s Midnight Ballad After Charlie Kirk’s Death—and the Hushed Arena That Became a…

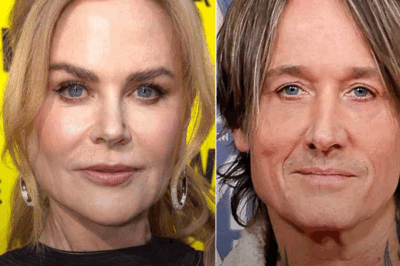

“When the Spotlight Turns Home”: Inside the Rumored Rift Between Nicole Kidman and Keith Urban—and the Moment Everything Quietly Broke

“When the Spotlight Turns Home”: Inside the Rumored Rift Between Nicole Kidman and Keith Urban—and the Moment Everything Quietly Broke…

“I Didn’t Know You Were Actually Handicapped”: A Blind Date Turns Cruel—Then a Stranger’s Hands Spoke a Language That Saved Three Lives

“I Didn’t Know You Were Actually Handicapped”: A Blind Date Turns Cruel—Then a Stranger’s Hands Spoke a Language That Saved…

At 36, I Married a Beggar Woman Who Later Bore Me Two Children — Until One Day, Three Luxury Cars Arrived and Revealed Her True Identity, Leaving the Entire Village in Shock…

At 36, I Married a Beggar Woman Who Later Bore Me Two Children — Until One Day, Three Luxury Cars…

SH0CKING NEWS: Tyrus DEMANDS NFL CANCEL Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl Halftime Show

SH0CKING NEWS: Tyrus DEMANDS NFL CANCEL Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl Halftime Show The stadium lights have not even dimmed. The…

Nine Months After Divorce, the Billionaire Confronts His Ex — Her Baby Faces a Life-Saving Surgery

Your 10:00 Is Waiting.” — The Email, the Baby, and the Lie That Rewired a Billion-Dollar Life The email arrived…

End of content

No more pages to load