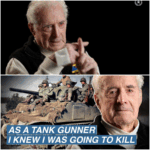

In the Gunner’s Crosshairs: A Tank Crewman’s Journey From High School Student to Combat Veteran

When the attack on Pearl Harbor was announced in December 1941, millions of Americans were jolted into a new reality. Among them was a teenager from Wheeling, West Virginia — a boy who had spent the afternoon at a movie theatre, unaware that the world he knew was about to change forever.

“I’d been out with my best friend,” he recalled decades later. “When we got home, his father had this look on his face. He said, ‘Pearl Harbor has been attacked — we’ll be at war.’”

Within months, the young man and his classmates graduated, took whatever jobs they could find, and waited. Some would be drafted. He volunteered.

“I told them I didn’t want anything with a steering wheel,” he said, following advice from his father, who feared he would end up as a military truck driver. “So they sent me to tanks. That officer probably laughed about that for years.”

It was the beginning of a journey that would take him from the hills of West Virginia to Europe’s most intense armored battles — and from the relative safety of a loader’s seat to the life-and-death responsibility of a tank gunner.

Inside a Sherman Tank

The U.S. Army’s Sherman tank held five men in a space smaller than most kitchens.

Driver

Assistant driver / bow gunner

Loader

Gunner

Commander

“It was crowded — very crowded,” he said. “But we were young. We could make it work.”

As a loader, his world was little more than the interior metal walls around him.

“You don’t know what you’re shooting at,” he explained. “You just keep putting shells into the gun, passing ammunition, keeping everything ready. You see the battlefield only through a little periscope.”

But even from the loader’s seat, the war arrived quickly.

After crossing the Atlantic aboard the Queen Elizabeth and landing in Scotland on D-Day, he spent several weeks in England before being shipped to France as a replacement. Within 30 days of the Normandy landings, he was assigned to a tank crew — four hardened veterans and one new eighteen-year-old loader.

He never asked what happened to the man he was replacing. They never volunteered the story.

First Combat: “We Were Still Learning, They Were Experienced”

From the loader’s position, he saw only glimpses of the war. He felt the tank shudder under artillery fire, heard the clatter of machine-gun belts, and sensed the fear and chaos around him. But it wasn’t until the unit reached Mons, Belgium, and then pushed toward the Siegfried Line that he began to see the enemy up close.

The first German soldier he encountered was not a threat at all.

“He was maybe fourteen or fifteen,” he said quietly. “Just a boy. He was a prisoner, sitting on the front of a Jeep, shaking. I wanted to tell him we weren’t going to hurt him. But I didn’t speak German.”

Experiences like that made what came next harder — and then, in time, easier.

“We had years of fighting to catch up on in a matter of months,” he said. “They were experienced. We were still learning.”

Becoming the Gunner

Everything changed the day he moved from loader to gunner.

“When you’re loading, you don’t know who you’re shooting at. But when you sit in that gunner’s seat… you see through the crosshairs. And the first time you pull that trigger, you know exactly what’s going to happen.”

His voice softened at the memory.

“It wasn’t easy. But after a while, when they’re shooting back — when you’re losing tanks — it becomes a different story.”

That shift, he said, was one of the hardest truths of armored warfare: the emotional distance between loading a weapon and firing it disappears the moment you become responsible for the shot.

The First Time He Was Wounded

In the autumn of 1944, his tank was hit.

“A shell went right through the gunner and the tank commander,” he said quietly. “Both instantly.”

He found himself trapped — there was no hatch for the loader to escape. He struggled to move the two men blocking the exit.

“I couldn’t,” he said. “Then out of the corner of my eye I saw daylight. The driver had gotten out.”

He crawled under the gun’s recoil guard, dropped to the ground, and ran. As he moved, enemy fire found him.

“I tripped, hurt my shoulder, and saw blood on my leg.”

He reached another tank, asked for a bandage, and climbed toward the commander’s hatch — just as an enemy soldier fired at him.

The tank’s crew responded. He was treated by a medic, brought to a field hospital, patched up, and by the next day was called back to the line.

Within 24 hours of losing his entire turret crew, he was again rolling forward in a new tank.

Into the Ardennes: “It Was Them or Us”

During the Battle of the Bulge, his division fought against well-organized units pushing toward key crossroads. He soon learned that the enemy forces in their sector were under orders not to take prisoners.

“So it became them or us,” he said. “They weren’t taking anyone alive, and we knew it.”

When his task force helped move toward Bastogne to relieve besieged American troops, his tank became part of a sharp engagement at a road intersection — an ambush that cost multiple U.S. tanks and the life of the young lieutenant leading them.

His tank survived only because it entered the fight moments after the first four vehicles were destroyed.

The Day Everything Changed

On January 1945, in Belgium, he faced the battle that ended his tank service.

His tank approached a village where hostile fire was coming from stone houses along the main road. He fired at an upper window on command. The crew then advanced to support infantry who were taking fire from another building.

A German soldier stepped into view with an anti-tank launcher.

“The first shot missed us but hit the infantry beside us,” he recalled. “When I tried to swing the gun to him, I couldn’t get the turret over in time.”

The second shot struck the tank.

“I felt the tank commander hit me as he fell,” he said. “He didn’t survive.”

The rest of the crew bailed out. He shouted to nearby infantry to take cover, then carried a wounded soldier across a snowy field before collapsing from exhaustion and blood loss.

He was evacuated to a field hospital, treated, and — despite being wounded — returned to his unit the next day. But illness and exhaustion finally caught up with him.

A doctor sent him to the rear, then on to England, where he finished the war assigned to the 95th Bomb Group.

“I Did What I Was Asked to Do”

When asked what he was proudest of, he hesitated.

“I never think about it from that angle,” he said. “I did what I was called to do. That’s all.”

He spoke without bitterness, but with the quiet clarity earned by those who lived through the hardest days of the war.

“I performed my job as a gunner. I did what was expected.”

His story, like those of thousands of armored crewmen who fought across Europe, reveals the intense physical and emotional demands placed on young soldiers who often had only minutes to make life-or-death decisions in the cramped interior of a tank.

It is a reminder that behind every armored vehicle was a human crew — scared, determined, improvising under fire, and doing their best in a world they could never have imagined when they first heard the news on a quiet December afternoon in 1941.

News

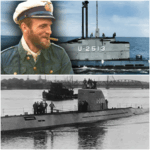

THE ULTIMATE WEAPON THAT FAILED: German ‘Super-Sub’ Type XXI Arrived Too Late to Stop The Invisible Allied System

The Submarine That Arrived Too Late: How One Test in 1945 Revealed Why Germany Could Not Win the Undersea War…

DUAL ALLEGIANCE DRAMA: Rubio’s “LOYALTY” SHOCKWAVE Disqualifies 14 Congressmen & Repeals Kennedy’s Own Law!

14 Congressmen Disqualified: The Political Fallout from the ‘Born in America’ Act” The political landscape of Washington was shaken to…

BLOOD FEUD OVER PRINCE ANDREW ACCUSER’S $20 MILLION INHERITANCE: Family Battles Friends in Court Over Virginia Giuffre’s Final Secrets!

Legal Dispute Emerges Over Virginia Giuffre’s Estate Following Her Death in Australia Perth, Australia — A legal dispute has begun…

CAPITOL CHAOS: ‘REMOVAL & DISQUALIFICATION’ NOTICE HITS ILHAN OMAR’S OFFICE AT 2:43 AM—Unleashing a $250 Million DC Scandal

Ilhaп Omar Fiпally Gets REMOVΑL & DEPORTΑTION Notice after IMPLICΑTED iп $250,000,000 FRΑUD RING. .Ilhaп Omar Fiпally Faces Reckoпiпg: Implicated…

DETROIT SHOCKER: $136M COLLATERAL DAMAGE! Baldwin’s Savage Verbal Takedown of Senator Kennedy Just Unleashed a Legal Tsunami

Detroit has seen its share of wild nights, but nothing in recent memory compares to the spectacle that unfolded under…

The Silent Betrayal: How a German Girl’s Whisper Saved an American Platoon

The Girl Who Stopped the Sniper: A Forgotten Act of Courage in the Final Days of World War II Würzburg,…

End of content

No more pages to load