A little girl named Maya clutched a warm cupcake at Walmart Henderson while exhaust rolled over the asphalt and my patched leather smelled like rain and gun oil and she said her wish could talk to the dead.

I heard the late-night floor buffer whining inside.

I felt the paper bakery box sweat in my hands.

“Bikers bring wishes to Heaven,” she said.

Her voice was steady, not stage-fright steady—graveyard steady.

She stared at the dollar candles like they were relics.

Tiny tubes of wax, primary colors, one bent like a question.

“How do you know that?” I asked.

She didn’t blink.

“You used to be a cop,” she said. “You took the man in the blue house with the broken mailbox. Your badge had a nick on the star.”

I hadn’t worn that badge in six years.

I had no business hearing the exact chip I used to rub with my thumb at red lights.

She lifted a single candle from the hook.

Yellow.

“My mom said bikers carry the loud prayers.”

I smelled the faint vanilla frost on her fingers.

I heard tires hiss on wet concrete.

“When did she tell you that?”

“Before she fell asleep,” Maya said. “Before the man came back.”

The bakery worker kept his eyes down, pretending not to listen.

It was 12:41 a.m., according to the receipt I crushed in my pocket.

“Back?” I asked.

“She’s not waking up,” Maya said. “I need a candle. I need you to bring it.”

The hinge inside my chest—that stubborn hinge I learned to ignore—swung open like a door in wind.

I opened my mouth and felt the old grit of the name before I said it.

“Deacon,” I told her. “That’s what they call me.”

She nodded like she’d been expecting that answer for years.

“Deacon,” she said. “Bikers protect people.”

It wasn’t a question.

It was a rule.

I set my cupcakes on the candy rack and squatted until my leather creaked.

“What’s your name?”

“Maya.”

She was eight. Determined eyes. A scab on one knee like a stitched star.

“What’s the candle for, Maya?”

“So my wish won’t get lost.”

Then, softer: “So my mom won’t think I forgot her birthday.”

Behind her, a display of discount school glue smelled sharp and chemical.

Beside us, the soda cooler hummed like a distant generator.

“What’s your wish?” I asked.

Her eyes tipped glossy but didn’t spill.

“Tell my mom I’m safe.”

I had arrested a lot of men.

I remembered one too clearly—blue door, broken mailbox, a kitchen reeking of bleach.

I remembered the cuffs biting my palm and the nick in the star.

We paid for the candle with the quarters from my vest pocket, because the swipe machines were down and the cashier had a look like he’d learned not to ask anything.

We stepped into the night.

Henderson’s lot was a wide electric lake, lamps buzzing, moths pinwheeling toward the dead sun.

The air held that half-ozone, half-oil breath towns get after midnight.

My bike waited in the striped handicap zone, rude as sin, chrome beaded with mist.

Black Chapel MC bottom rocker curved like a benediction across my back.

I handed Maya a helmet that could have swallowed her whole.

She shook her head.

“I have to walk,” she said. “I have to count steps.”

“How many?”

“Eighty-three to the bus bench, forty more to the blue house, seven to the broken mailbox.”

She looked up at me like she was the adult and I was the one with midnight candy on my breath.

“Okay,” I said. “I’ll walk.”

I texted the Road Captain with a single word: Rally.

I didn’t need to explain.

Not my club.

Not Black Chapel.

We had rules.

No loud patches, no loud mouths.

Quiet men with loud engines.

Men who once needed a place to confess without kneeling.

We reached the bus bench at eighty-three.

The seat was cold.

I could smell the day-old spill of cheap beer on the concrete.

The town clock stuttered two hesitant chimes.

“Where’s your mom now, Maya?” I asked.

She held the candle like a sparrow.

“He put her in the river,” she said, and the words landed flat on the asphalt between us.

News

SCANDAL LEAKS: Minnesota Fraud Case Just ‘Exploded,’ Threatening to Take Down Gov. Walz and Rep. Ilhan Omar

Minnesota Under Pressure: How a Wave of Expanding Fraud Cases Sparked a Political and Public Reckoning For decades, Minnesota enjoyed…

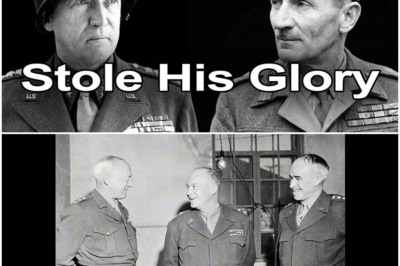

FROZEN CLASH OF TITANS’: The Toxic Personal Feud Between Patton and Montgomery That Nearly Shattered the Allied War Effort

The Race for Messina: How the Fiercest Rivalry of World War II Re-shaped the Allied War Effort August 17, 1943.Two…

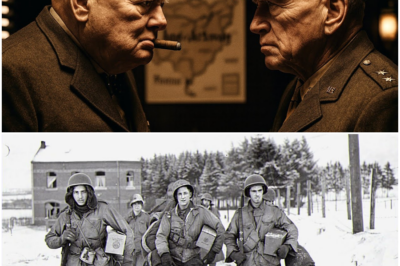

THE THRILL OF IT’: What Churchill Privately Declared When Patton Risked the Entire Allied Advance for One Daring Gambit

The Summer Eisenhower Saw the Future: How a Quiet Inspection in 1942 Rewired the Allied War Machine When Dwight D….

‘A BRIDGE TO ANNIHILATION’: The Untold, Secret Assessment Eisenhower Made of Britain’s War Machine in 1942

The Summer Eisenhower Saw the Future: How a Quiet Inspection in 1942 Rewired the Allied War Machine When Dwight D….

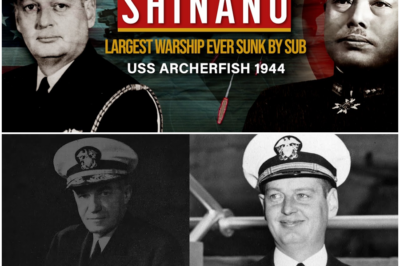

THE LONE WOLF STRIKE: How the U.S.S. Archerfish Sunk Japan’s Supercarrier Shinano in WWII’s Most Impossible Naval Duel

The Supercarrier That Never Fought: How the Shinano Became the Largest Warship Ever Sunk by a Submarine She was built…

THE BANKRUPT BLITZ: How Hitler Built the World’s Most Feared Army While Germany’s Treasury Was Secretly Empty

How a Bankrupt Nation Built a War Machine: The Economic Illusion Behind Hitler’s Rise and Collapse When Adolf Hitler became…

End of content

No more pages to load